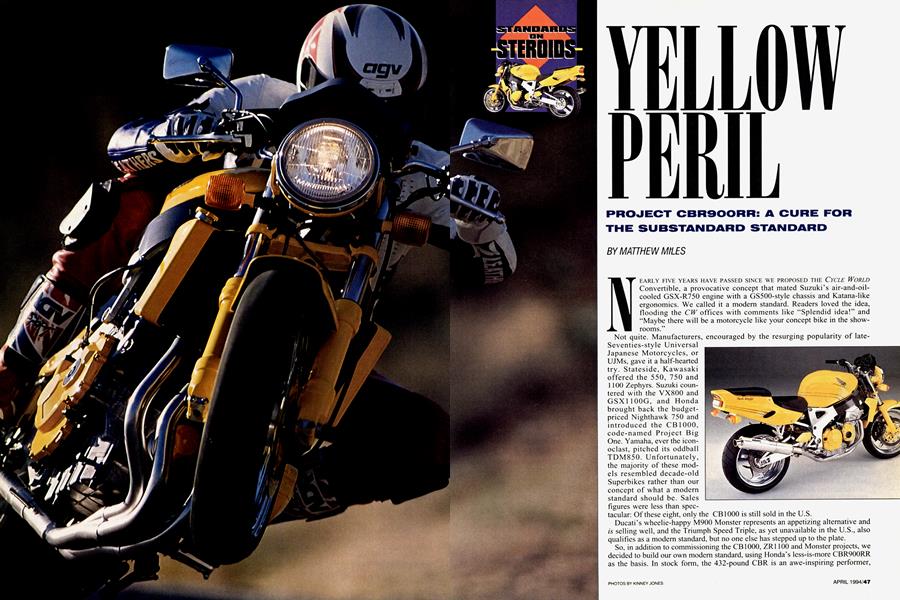

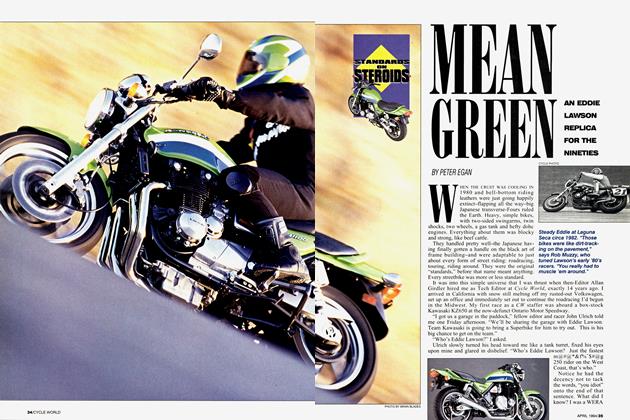

YELLOW PERIL

PROJECT CBR900RR: A CURE FOR THE SUBSTANDARD STANDARD

MATTHEW MILES

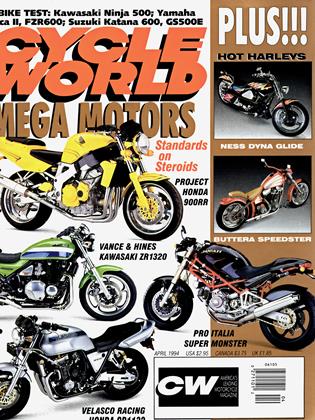

NEARLY FIVE YEARS HAVE PASSED SINCE WE PROPOSED THE CYCLE WORLD Convertible, a provocative concept that mated Suzuki’s air-and-oil-cooled GSX-R750 engine with a GS500-style chassis and Katana-like ergonomics. We called it a modern standard. Readers loved the idea, flooding the CW offices with comments like “Splendid idea!" and “Maybe there will be a motorcycle like your concept bike in the showrooms."

Not quite. Manufacturers, encouraged by the resurging popularity of late-

Seventies-style Universal Japanese Motorcycles, or UJMs, gave it a half-hearted try. Stateside, Kawasaki offered the 550, 750 and 1100 Zephyrs. Suzuki countered with the VX800 and GSX1100G, and Honda brought back the budgetpriced Nighthawk 750 and introduced the CB1000, code-named Project Big One. Yamaha, ever the iconoclast, pitched its oddball TDM850. Unfortunately, the majority of these models resembled decade-old Superbikes rather than our concept of what a modern standard should be. Sales figures were less than spec-

tacular: Of these eight, only the CB1000 is still sold in the U.S.

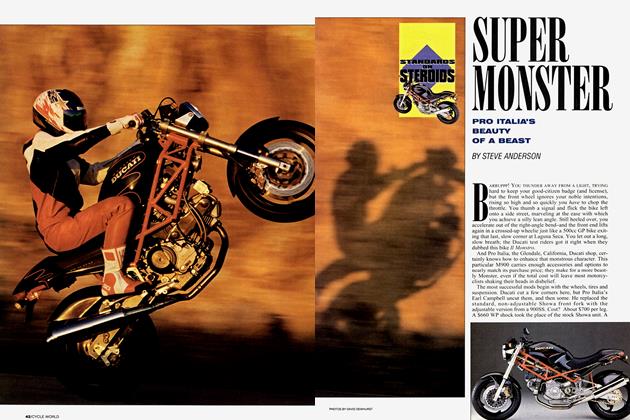

Ducati’s wheelie-happy M900 Monster represents an appetizing alternative and is selling well, and the Triumph Speed Triple, as yet unavailable in the U.S., also qualifies as a modem standard, but no one else has stepped up to the plate.

So, in addition to commissioning the CB1000, ZR1100 and Monster projects, we decided to build our own modem standard, using Honda’s less-is-more CBR900RR as the basis. In stock form, the 432-pound CBR is an awe-inspiring performer, blasting through the quarter-mile in 10.59 seconds, and achieving a top speed of 159 mph. The CBR900RR also digests comers better than any big-bore sportbike on the market, prompting us to declare it 1993’s Best Superbike in our annual Ten Best Bikes voting.

Converting the CBR to standard status wasn’t dauntingly difficult. American Honda’s Dirk Vandenberg got the ball rolling by removing the fairing and headlights, after which he fitted a CB1000 top clamp, handlebar and headlight.

Vandenberg has more than just a passing interest in our project bike. In his 18 years with American Honda-most recently as chief product evaluator-the 43-year-old Michigan native has seen a lot of projects come and go. A few reached production, while others have fallen by the wayside. He thinks this bike has potential.

“Personally, I believe there is an older sportbike crowd, a market segment that wants all the riding performance of a CBR900RR without the cramped riding position and the roadracer-replica bodywork,’’ says

Vandenberg. “That crowd, I feel, appreciates the moremechanical, technical look of the unfaired sportbike. That’s what gives it emotion.’’

Pruned of its plastic, the Project 900 took on a more compact appearance, but the CBR’s rotund fuel tank now looked swollen and out of proportion. Honda fabricator Tom Jobe came to our aid, molding the fuel tank into a sleeker, slightly-less-bulbous shape. Jobe also modified the radiator, rerouted ancillary coolant hoses, then hammered out a set of aluminum shrouds.

As the quick-revving, 893cc inline-Four already sends 114 horsepower to the rear wheel, we concentrated our efforts on trimming weight. Stripping the CBR’s plastic fairing helped, as did the addition of Performance Machine wheels, a 4-into-2-into-l Mike Velasco Racing exhaust system, and aluminum and titanium hardware from Indigo Sports. So unencumbered, our fully street-legal 900 now weighs-in at 400 pounds dry, 32 less than stock.

Velasco also supplied a Factory jet kit, which included adjustable needles (stock taper), and a 2-degree ignition advancer. In this lightly modified tune, the engine pumped out 119 horsepower at 10,750 rpm, a gain of 5 horsepower over stock.

As expected, straight-line performance is remarkable. With Road Test Editor Don Canet at the controls, the banana-yellow 900 sprinted through the quarter-mile in 10.62 seconds at 132 mph. Canet attributed the same-asstock performance to the bike’s increased tendency to wheelie off the startline. Top speed for the unfaired 900, as indicated by the CW radar gun, was 152 mph.

Few production motorcycles wheelie as readily as a stock CBR900RR, but our reduced-calorie project bike lifts its front end with startling ease. “The thing will wheelie in third gear, at an indicated 90 mph,” relayed a euphoric Canet. “Just snap the throttle and give it a tug. It’s wild.”

First impressions of the Project 900’s handling were eyeopening, as well. Steering response is instantaneous, thanks to the CBR600F2-spec 120/70 Bridgestone Battlax radial front tire, 17-inch PM wheel and the added leverage provided by the wide, tube-type handlebar. Initial turn-in requires only a light nudge on the bar, and S-bend transitions are an afterthought. Ham-fisted riders needn’t apply.

That’s not to say aggressive riding is not rewarded. Inputs, though, must be made with thought and precision. Overzealous use of the front brakes-stock four-piston calipers and rotors, with Braking pads and CBR600-length Fren-Tubo Kevlar brake lines-for example, will easily lift the 5.5-inch wide rear wheel waaay off the pavement, plastering the rider’s eyeballs to his faceshield.

Impressive stopping power aside, what our Project 900 does better than any other standard-retro or otherwise-is shatter the self-esteem of puffed-up sportbike pilots. Fairing or not, this lightweight flyer is still a CBR900RR, and on a twisty road it performs like one. Bolstered by the more-upright riding position, prolonged outings are more pleasurable, too.

Further adding to that improved comfort is the Clean Racing-modified fork, which is more compliant than stock, yet firm enough for serious backroad blasting. Even so, there’s no getting around the 900’s compact, 55-inch wheelbase, which sacrifices some ride quality for responsive handling.

Of course, no project is without glitches. Fitting the tubular handlebar offers limited access to the fork’s spring-

preload and rebound-damping adjusters, and the Magna 750 mirrors, though stylish, provide a limited rear view. Also, the stock throttle cables are slightly too short for the taller handlebar, which results in sticky throttle action at full right lock. Custom-made cables would be a worthwhile expenditure. Driveline lash is also a problem, a result of the PM wheel’s solid, non-cush design.

We’ve had good success with Competition Werkes Fender Eliminator Kits on past projects, but vague installation instructions for the CBR900 and sharp-edged stainless-steel componentry induced criticism this time. What’s more, the CBR’s inner fender had to be hacked in half to facilitate mounting, eliminating the handy storage area.

The MVR pipe also presented a couple of problems. The $420 system is nicely crafted, but lightly baffled, which makes short-shifting essential in-town. In addition, early examples were designed for use with rearsets, and cause brake pedal clearance problems with the stock footpeg setup. The quick-and-dirty fix, says Velasco, is to rotate the section for added clearance. This helped, but didn’t solve the prob-

lem. As a last-minute solution, we dented the section to achieve the necessary clearance.

Even with its minor foibles, duplicating our Project 900 would be relatively easy. The basic necessities-headlight, handlebar and associated hardware-can be purchased through local dealers. The custom top clamp we added will be harder to come by; machin-

ist Anthony DeChellis has no intention of reproducing additional examples.

Will Honda build a production version of this bike? Difficult to say. Vandenberg says consumer interest in the bike could spark renewed research into the category.

What we do know, as evidenced by the Vance & Hines ZR1100 and Velasco CB1000 is that old-style standards are better bikes with pumped-up motors and catchy paint jobs. We also know that the Ducati Monster, expertly gilded by the good folks at Pro Italia, comes very close to being the ideal modem standard-halving its price and mixing in another 10 horsepower would provide the missing ingredients. All three are terrific fun to ride.

But for those enthusiasts whose image of two-wheeled excitement includes no-apologies performance and all-day comfort and the hairy-chested style of a non-faired bike, you’re flat out of luck. We’ve got a true modem standard; we know how good it is. But you can’t have it.

And that’s a crying shame. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

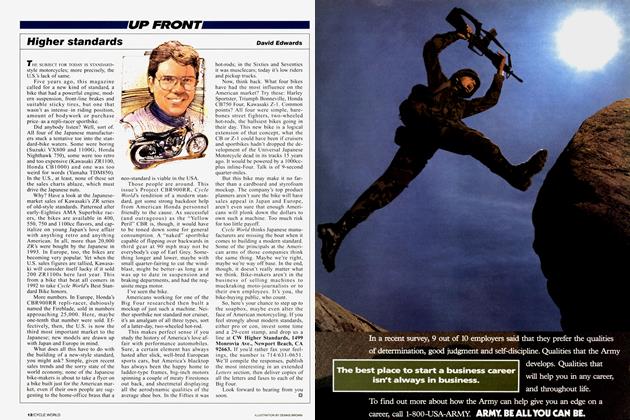

Up FrontHigher Standards

April 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsShould You Buy A German Bike?

April 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCClass Struggles

April 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupVr Harley Superbike For the Street?

April 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupVr 1000 Parts For the People

April 1994 By Robert Hough