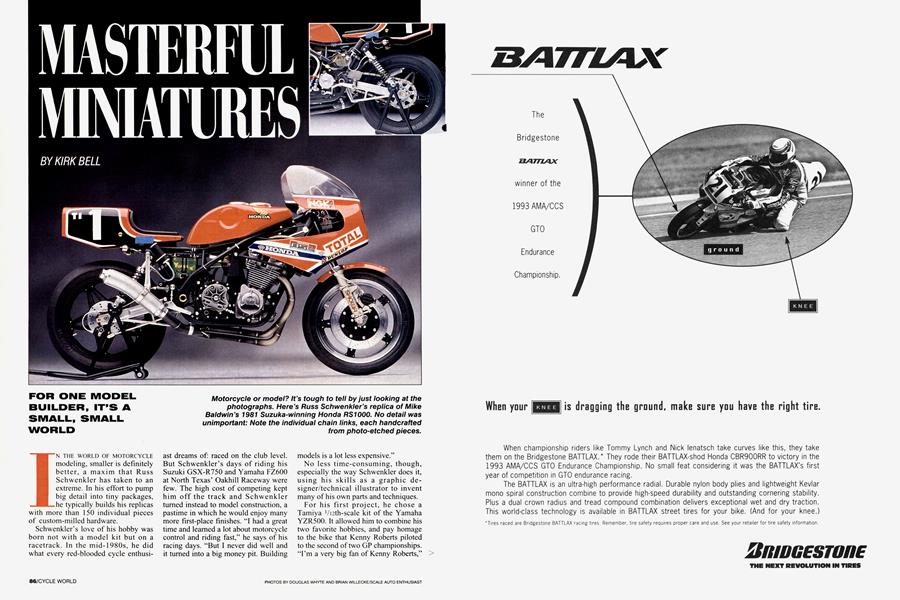

MASTERFUL MINIATURES

KIRK BELL

FOR ONE MODEL BUILDER, IT’S A SMALL, SMALL WORLD

IN THE WORLD OF MOTORCYCLE modeling, smaller is definitely better, a maxim that Russ Schwenkler has taken to an extreme. In his effort to pump big detail into tiny packages, he typically builds his replicas with more than 150 individual pieces of custom-milled hardware.

Schwenkler’s love of his hobby was born not with a model kit but on a racetrack. In the mid-1980s, he did what every red-blooded cycle enthusiast dreams of: raced on the club level. But Schwenkler’s days of riding his Suzuki GSX-R750 and Yamaha FZ600 at North Texas’ Oakhill Raceway were few. The high cost of competing kept him off the track and Schwenkler turned instead to model construction, a pastime in which he would enjoy many more first-place finishes. “I had a great time and learned a lot about motorcycle control and riding fast,” he says of his racing days. “But I never did well and it turned into a big money pit. Building models is a lot less expensive.”

No less time-consuming, though, especially the way Schwenkler does it, using his skills as a graphic designer/technical illustrator to invent many of his own parts and techniques.

For his first project, he chose a Tamiya 1/12th-scale kit of the Yamaha YZR500. It allowed him to combine his two favorite hobbies, and pay homage to the bike that Kenny Roberts piloted to the second of two GP championships. “I’m a very big fan of Kenny Roberts,” Schwenkler explains. “And I always thought that bike was particularly attractive, both visually and technically.” After thoroughly researching Roberts’ motorcycle in back issues of magazines, he began construction. Tamiya’s kit provided just the skeleton. Using a computer-aided design program, he produced threedimensional engineering drawings for some 65 different parts. These drawings were sent to machinist Cody Graylan, who cut the precisely specified parts. In addition to the machined items, Schwenkler created roughly two dozen camera-ready drawings that would be used to create a set of photo-etched detail pieces. Photo-etching is a process in which drawings of scale-model parts on transparent drafting film are placed on photosensitive metal and exposed to chemicals. The treatment creates a thin piece of metal-in this case, nickel silver-that reflects the original artwork. The use of photoetched parts greatly enhances the overall level of detail on scale models.

Schwenkler then fabricated another 35 pieces from such materials as brass, plastic and aluminum to further detail the Yamaha. All told, 135 pieces of his miniature were scratch-built or modified in some way.

The completed Yamaha was good, but not perfect in Schwenkler’s exacting judgment. Once finished, he immediately set to work on building an even better model.

This time, Russ chose Tamiya’s Vi2th-scale Honda RSI000 endurance racer kit. He hoped this model could better display his fine detailing work. “On the Yamaha, if I had the fairing in place, it hid all the chassis detail. And if 1 removed the fairing, I destroyed the lines of the bike. So, I wanted a model that would hold its own as a complete unit without having to disassemble it for display.” By constructing this kit as Mike Baldwin’s 1981 Suzuka 8-Hour race winner, Schwenkler could use a half-fairing and leave the chassis exposed.

Once again, he began by referring to old issues of motorcycle magazines. But this time he also examined a fullscale motorcycle, a Honda CB900, the production model upon which the RS 1000 racer was based.

Schwenkler decided that only about two dozen or so of the kit’s 100-plus plastic parts were good enough for his model. Two more sets of threedimensional drawings were created, calling for 251 machined parts and 45 photo-etched tidbits.

Schwenkler then turned his attention to the remaining kit parts. The frame was cut to correct a flaw in the rake and to replace some sections with plastic rod. To produce the appearance of a seamless frame, the modified unit had to be rebuilt and painted before engine installation.

Like the Yamaha, the Honda was also embellished with several parts that Schwenkler fabricated from brass, plastic and aluminum. The front fork, triple-clamps, brakes and wheels were redone in metal to create a sturdier and more realistic unit.

Down to every bolt, Allen screw or look-alike titanium fastener, the RS’s hardware was reproduced in aluminum. Machined sparkplugs, velocity stacks, carburetor details, clutchand throttle-cable fittings and dozens of other details have been added to the engine/transmission assembly. Schwenkler routed all of the electrical wiring, oil plumbing, and fuel and vacuum lines. In addition, he constructed a photo-etched clutch basket, visible through the ventilated clutch cover.

Schwenkler created the rear shocks from four machined pieces, complete with springs sourced from a specialtyengineering supplier. The rear-brake rotor and hub are turned from aluminum and enhanced with a scratchbuilt caliper and torque arm. Several hundred photo-etched rivets, each one hand-applied, detail the chain. All of the foot controls for the shifter and rear-brake mechanisms have been hand-made from sheet aluminum, stainless steel, photo-etched parts and watch mechanicals.

The master modeler’s hard work paid off. His finished product captured a coveted Best in Show award at the modeling world’s equivalent of the Pebble Beach Concours, the 1993 Greater Salt Lake International Model Car Championship.

The story of Schwenkler and his scale cycles doesn’t end here, however. He is already hard at work on another bike, a Vance & Hines Yamaha Superbike, hoping to prove yet again that a motorcycle doesn’t have to be full-scale to be a big-time classic. E2

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHigher Standards

April 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsShould You Buy A German Bike?

April 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCClass Struggles

April 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupVr Harley Superbike For the Street?

April 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupVr 1000 Parts For the People

April 1994 By Robert Hough