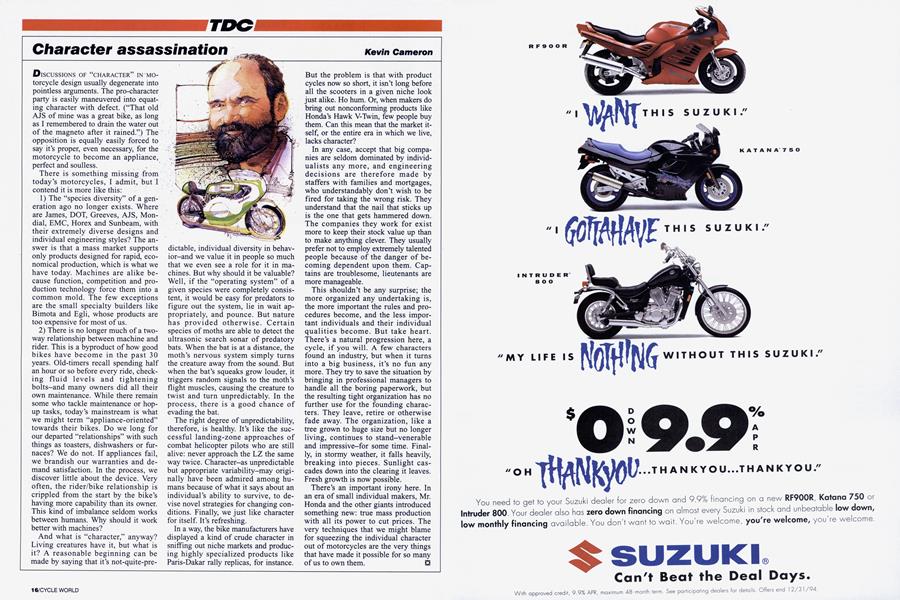

Character assassination

Kevin Cameron

TDC

DISCUSSIONS OF “CHARACTER” IN MOtorcycle design usually degenerate into pointless arguments. The pro-character party is easily maneuvered into equating character with defect. (“That old AJS of mine was a great bike, as long as I remembered to drain the water out of the magneto after it rained.”) The opposition is equally easily forced to say it’s proper, even necessary, for the motorcycle to become an appliance, perfect and soulless.

There is something missing from today’s motorcycles, I admit, but I contend it is more like this:

1) The “species diversity” of a generation ago no longer exists. Where are James, DOT, Greeves, AJS, Mondial, EMC, Horex and Sunbeam, with their extremely diverse designs and individual engineering styles? The answer is that a mass market supports only products designed for rapid, economical production, which is what we have today. Machines are alike because function, competition and production technology force them into a common mold. The few exceptions are the small specialty builders like Bimota and Egli, whose products are too expensive for most of us.

2) There is no longer much of a twoway relationship between machine and rider. This is a byproduct of how good bikes have become in the past 30 years. Old-timers recall spending half an hour or so before every ride, checking fluid levels and tightening bolts-and many owners did all their own maintenance. While there remain some who tackle maintenance or hopup tasks, today’s mainstream is what we might term “appliance-oriented” towards their bikes. Do we long for our departed “relationships” with such things as toasters, dishwashers or furnaces? We do not. If appliances fail, we brandish our warranties and demand satisfaction. In the process, we discover little about the device. Very often, the rider/bike relationship is crippled from the start by the bike’s having more capability than its owner. This kind of imbalance seldom works between humans. Why should it work better with machines?

And what is “character,” anyway? Living creatures have it, but what is it? A reasonable beginning can be made by saying that it’s not-quite-predictable, individual diversity in behavior-and we value it in people so much that we even see a role for it in machines. But why should it be valuable? Well, if the “operating system” of a given species were completely consistent, it would be easy for predators to figure out the system, lie in wait appropriately, and pounce. But nature has provided otherwise. Certain species of moths are able to detect the ultrasonic search sonar of predatory bats. When the bat is at a distance, the moth’s nervous system simply turns the creature away from the sound. But when the bat’s squeaks grow louder, it triggers random signals to the moth’s flight muscles, causing the creature to twist and turn unpredictably. In the process, there is a good chance of evading the bat.

The right degree of unpredictability, therefore, is healthy. It’s like the successful landing-zone approaches of combat helicopter pilots who are still alive: never approach the LZ the same way twice. Character-as unpredictable but appropriate variability-may originally have been admired among humans because of what it says about an individual’s ability to survive, to devise novel strategies for changing conditions. Finally, we just like character for itself. It’s refreshing.

In a way, the bike manufacturers have displayed a kind of crude character in sniffing out niche markets and producing highly specialized products like Paris-Dakar rally replicas, for instance. But the problem is that with product cycles now so short, it isn’t long before all the scooters in a given niche look just alike. Ho hum. Or, when makers do bring out nonconforming products like Honda’s Hawk V-Twin, few people buy them. Can this mean that the market itself, or the entire era in which we live, lacks character?

In any case, accept that big companies are seldom dominated by individualists any more, and engineering decisions are therefore made by staffers with families and mortgages, who understandably don’t wish to be fired for taking the wrong risk. They understand that the nail that sticks up is the one that gets hammered down. The companies they work for exist more to keep their stock value up than to make anything clever. They usually prefer not to employ extremely talented people because of the danger of becoming dependent upon them. Captains are troublesome, lieutenants are more manageable.

This shouldn’t be any surprise; the more organized any undertaking is, the more important the rules and procedures become, and the less important individuals and their individual qualities become. But take heart. There’s a natural progression here, a cycle, if you will. A few characters found an industry, but when it turns into a big business, it’s no fun any more. They try to save the situation by bringing in professional managers to handle all the boring paperwork, but the resulting tight organization has no further use for the founding characters. They leave, retire or otherwise fade away. The organization, like a tree grown to huge size but no longer living, continues to stand-venerable and impressive-for some time. Finally, in stormy weather, it falls heavily, breaking into pieces. Sunlight cascades down into the clearing it leaves. Fresh growth is now possible.

There’s an important irony here. In an era of small individual makers, Mr. Honda and the other giants introduced something new: true mass production with all its power to cut prices. The very techniques that we might blame for squeezing the individual character out of motorcycles are the very things that have made it possible for so many of us to own them. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Endless Ride

December 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsSaving For A Vincent

December 1994 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1994 -

Roundup

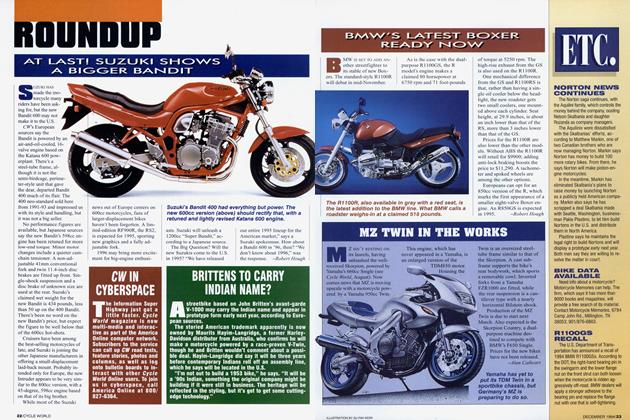

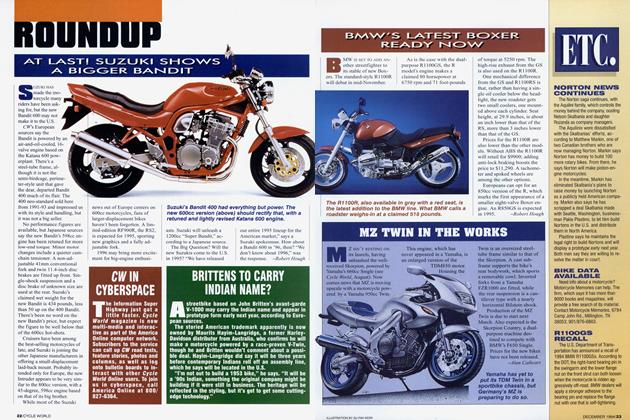

RoundupAt Last! Suzuki Shows A Bigger Bandit

December 1994 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupCw In Cyberspace

December 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupBrittens To Carry Indian Name?

December 1994