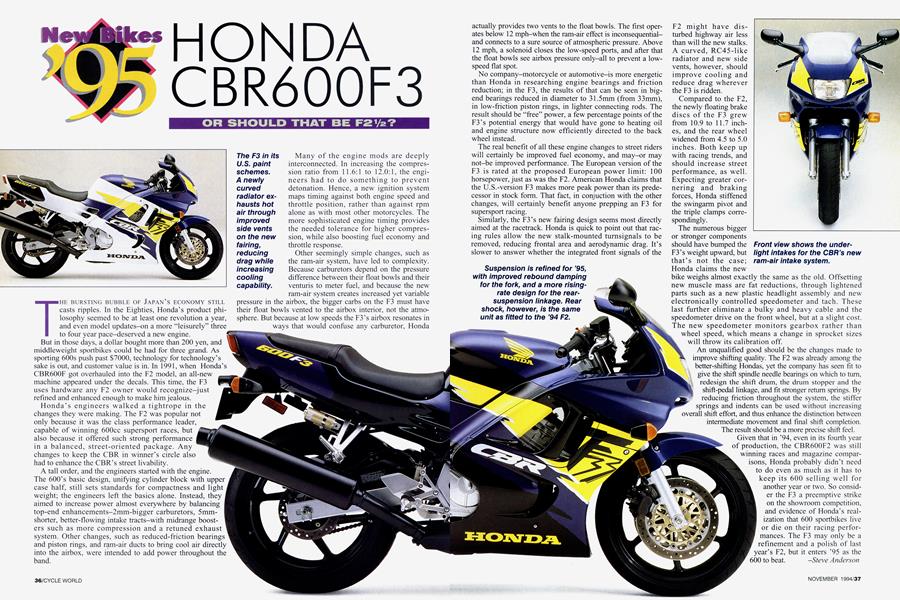

HONDA CBR600F3

New Bikes '95

OR SHOULD THAT BE F2½?

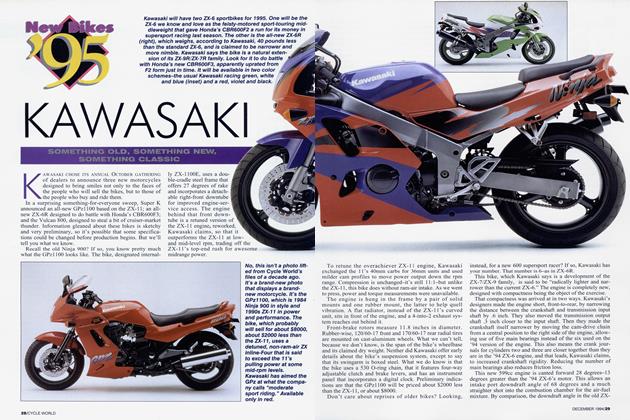

THE BURSTING BUBBLE OF JAPAN'S ECONOMY STILL casts ripples. In the Eighties, Honda's product philosophy seemed to be at least one revolution a year, and even model updates—on a more "leisurely" three to four year pace—deserved a new engine.

But in those days, a dollar bought more than 200 yen, and middleweight sportbikes could be had for three grand. As sporting 600s push past $7000, technology for technology’s sake is out, and customer value is in. In 1991, when Honda’s CBR600F got overhauled into the F2 model, an all-new machine appeared under the decals. This time, the F3 uses hardware any F2 owner would recognize-just refined and enhanced enough to make him jealous.

Honda’s engineers walked a tightrope in the changes they were making. The F2 was popular not only because it was the class performance leader, capable of winning 600cc supersport races, but also because it offered such strong performance in a balanced, street-oriented package. Any changes to keep the CBR in winner’s circle also had to enhance the CBR’s street livability.

A tall order, and the engineers started with the engine.

The 600’s basic design, unifying cylinder block with upper case half, still sets standards for compactness and light weight; the engineers left the basics alone. Instead, they aimed to increase power almost everywhere by balancing top-end enhancements-2mm-bigger carburetors, 5mmshorter, better-flowing intake tracts-with midrange boosters such as more compression and a retuned exhaust system. Other changes, such as reduced-friction bearings and piston rings, and ram-air ducts to bring cool air directly into the airbox, were intended to add power throughout the band. Many of the engine mods are deeply interconnected. In increasing the compres-

sion ratio from 11.6:1 to 12.0:1, the engi-

neers had to do something to prevent

detonation. Hence, a new ignition system

maps timing against both engine speed and throttle position, rather than against rpm alone as with most other motorcycles. The more sophisticated engine timing provides the needed tolerance for higher compression, while also boosting fuel economy and throttle response.

Other seemingly simple changes, such as

the ram-air system, have led to complexity. Because carburetors depend on the pressure difference between their float bowls and their

venturis to meter fuel, and because the new ram-air system creates increased yet variable pressure in the airbox, the bigger carbs on the F3 must have their float bowls vented to the airbox interior, not the atmosphere. But because at low speeds the F3’s airbox resonates in ways that would confuse any carburetor, Honda actually provides two vents to the float bowls. The first operates below 12 mph-when the ram-air effect is inconsequentialand connects to a sure source of atmospheric pressure. Above 12 mph, a solenoid closes the low-speed ports, and after that the float bowls see airbox pressure only-all to prevent a lowspeed flat spot.

No company-motorcycle or automotive-is more energetic than Honda in researching engine bearings and friction reduction; in the F3, the results of that can be seen in bigend bearings reduced in diameter to 31.5mm (from 33mm), in low-friction piston rings, in lighter connecting rods. The result should be “free” power, a few percentage points of the F3’s potential energy that would have gone to heating oil and engine structure now efficiently directed to the back wheel instead.

The real benefit of all these engine changes to street riders will certainly be improved fuel economy, and may-or may not-be improved performance. The European version of the F3 is rated at the proposed European power limit: 100 horsepower, just as was the F2. American Honda claims that the U.S.-version F3 makes more peak power than its predecessor in stock form. That fact, in conjuction with the other changes, will certainly benefit anyone prepping an F3 for supersport racing.

Similarly, the F3’s new fairing design seems most directly aimed at the racetrack. Honda is quick to point out that racing rules allow the new stalk-mounted turnsignals to be removed, reducing frontal area and aerodynamic drag. It’s slower to answer whether the integrated front signals of the

F2 might have disturbed highway air less than will the new stalks. A curved, RC45-like radiator and new side vents, however, should improve cooling and reduce drag wherever the F3 is ridden.

Compared to the F2, the newly floating brake discs of the F3 grew from 10.9 to 11.7 inches, and the rear wheel widened from 4.5 to 5.0 inches. Both keep up with racing trends, and should increase street performance, as well. Expecting greater cornering and braking forces, Honda stiffened the swingarm pivot and the triple clamps correspondingly.

The numerous bigger or stronger components should have bumped the F3’s weight upward, but that’s not the case; Honda claims the new

bike weighs almost exactly the same as the old. Offsetting new muscle mass are fat reductions, through lightened parts such as a new plastic headlight assembly and new electronically controlled speedometer and tach. These last further eliminate a bulky and heavy cable and the speedometer drive on the front wheel, but at a slight cost. The new speedometer monitors gearbox rather than wheel speed, which means a change in sprocket sizes will throw its calibration off.

An unqualified good should be the changes made to improve shifting quality. The F2 was already among the better-shifting Hondas, yet the company has seen fit to give the shift spindle needle bearings on which to turn, redesign the shift drum, the drum stopper and the shift-pedal linkage, and fit stronger return springs. By reducing friction throughout the system, the stiffer springs and indents can be used without increasing overall shift effort, and thus enhance the distinction between intermediate movement and final shift completion. The result should be a more precise shift feel. Given that in ’94, even in its fourth year of production, the CBR600F2 was still winning races and magazine comparisons, Honda probably didn’t need to do even as much as it has to keep its 600 selling well for another year or two. So consider the F3 a preemptive strike on the showroom competition, and evidence of Honda’s realization that 600 sportbikes live or die on their racing performances. The F3 may only be a refinement and a polish of last year’s F2, but it enters ’95 as the 600 to beat. -Steve Anderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontIncident On the Angeles Crest

November 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGs-Ing It

November 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCEngine Architecture

November 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Reveals Trick 250

November 1994 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Gets Savage For 1995

November 1994