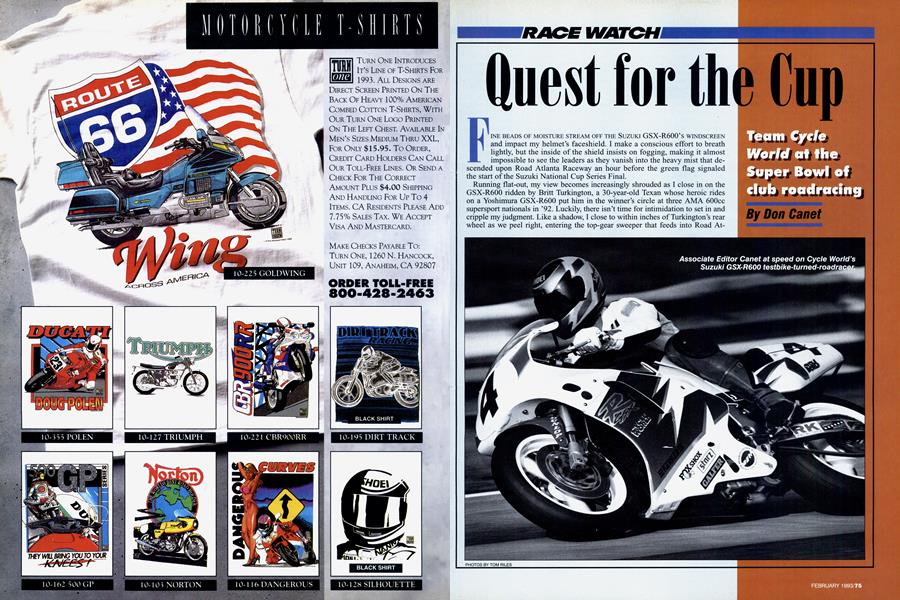

Quest for the Cup

RACE WATCH

Team Cycle World at the Super Bowl of club roadracing

Don Canet

FINE BEADS OF MOISTURE STREAM OFF THE SUZUKI GSX-R600's WINDSCREEN and impact my helmet's faceshield. I make a conscious effort to breath lightly, but the inside of the shield insists on fogging, making it almost impossible to see the leaders as they vanish into the heavy mist that descended upon Road Atlanta Raceway an hour before the green flag signaled the start of the Suzuki National Cup Series Final.

Running flat-out, my view becomes increasingly shrouded as I close in on the GSX-R600 ridden by Britt Turkington, a 30-year-old Texan whose heroic rides on a Yoshimura GSX-R600 put him in the winner's circle at three AMA 600cc supersport nationals in `92. Luckily, there isn't time for intimidation to set in and cripple my judgment. Like a shadow, I close to within inches of Turkington's rear wheel as we peel right, entering the top-gear sweeper that feeds into Road Atlanta’s infamous “Gravity Cavity,” a rollercoaster-like section where the track plunges 100 feet. Back in my full-time racing days, I crashed in the bottom of this dip at 160 mph on a nitrous-oxide-injected llOOcc FormulaUSA bike, an event that hastened a career change to journalism.

The memory of that terrifying experience is still fresh as I pull out of the draft and crawl alongside my opponent as we rush down into the heart of the dip. The slingshot effect gives my bike enough momentum to complete the pass before reaching the kink at the bottom of the hill. A mixed feeling of accomplishment and relief swells over me as I brake for the Bridge Turn, coming up fast.

What’s a moto-journalist like me doing getting in the way of the fast guys, you ask? Well, the Suzuki National Cup Series has become one of the mainstays of grass-roots roadracing in America and an excellent training ground for future stars, so in the spirit of participatory journalism, Cycle World decided to take a close-up look.

Started in 1986, the series is a contingency program that pays roadracers for high finishes at selected club events. “It was a simple marketing decision,” says a Suzuki spokesman about the series’ inception. “We thought it was the best way to promote the product. It helped set the GSX-R’s reputation, increased national exposure and showed that Suzuki was involved in the sport.” In the series’ current form, the country is divided into 10 regions, each region typically having 8 to 10 designated Suzuki Cup events over the course of the season, with contingency money paid to GSX-R600, 750 and 1100 riders placing in the top 10 overall in class, and Cup points being awarded down to 14th place. At the end of the season, the top five GSXR600, 750 and 1100 riders from each region are invited to the Road Atlanta Finals. Suzuki posted contingency money at 73 regional events in 1992, paying $500 for a win, $300 for second, $250 for third and so on down to $25 for 10th place. Not enough to retire on, but a good way of defraying entry fees, tire costs, fuel bills, etc. Running a GSX-R in Region 10-the AMA/CCS National Supersport Championship-paid $1500 for a win, breaking down to $450 for a fifth.

For many of the 240 registered Suzuki Cup racers this past year, the real motivation was the National Final, where big trophies, $5000 for a class win and the attention of the factory teams awaited.

Two-time World Superbike Champion Doug Polen is the most notable rider who has used Cup racing as a springboard for a professional racing career. Polen took the country by storm in ’86, the series’ inaugural year, traveling coast to coast, hitting a Cup race nearly every weekend, grossing $90,000 in contingency earnings. Others who made their > names Cup racing include ’92 AMA Superbike Champion Scott Russell, ’90 AMA Superbike Champion Jamie James, ’91 Daytona 200 winner David Sadowski and ’90 WERA FUSA Champion Mike Smith.

Team Cycle World's quest for the Cup started with race-prepping our ’92 GSX-R600 testbike (see “GrassRoots Racebike,” page 76) and checking the schedule to see how many Southwest Region Cup qualifier rounds we could make. The first outing was at Willow Springs Raceway, our home track, where I worked up from the back row of a 33-bike field, finishing fifth overall. Starting mid-field on my next visit to Willow Springs, I was able to break clear of the main pack and make a run at the leaders, turning the fastest lap of the race in the process, but eventually finishing third behind a Honda CBR600F2 and a Yamaha FZR600. At the next race in Las Vegas, Nevada, I finished a close second. The elusive win came in the final regional race at Firebird Raceway in Phoenix, Arizona. With it, I’d had wrapped up the 600 Cup points lead in the region and was all set for Road Atlanta.

Based on my regional points, which placed me fourth in the country, I received a second-row grid position in the Saturday’s four-lap GSX-R600 heat race at the Cup Final. Heat-race results are used to determine gridding for the Sunday main. But my sixthplace finish slipped me back to the third row for the final, not an encouraging sign. I was turning times 3 seconds a lap faster than in practice, but had run into a serious handling flaw that had the bike sliding all over the track. As it turned out, I traced the problem to low tire inflation caused by an inaccurate pressure gauge, a problem easily fixed.

Handling gremlins banished, I knocked another 1.5 seconds off my lap times and found myself right in the thick of things during the 600 final.

With the Gravity Cavity pass, I have Turkington behind me, and set sights on Dave Sadowski running in fifth place. I tuck in for yet another run down the long back straight, slowly catching Sadowski’s draft. I have momentum built up, but it’s a bit too late as we drop into the dip and I have to throttle back to avoid getting chopped off at the kink. My prudence pays off on the very next go-’round. With a better drive off of the turn leading onto the straightaway, this time there’s no need to roll out of it as I slip past Sadowski. The next lap, I catch and pass Chuck Graves-fourth place, not too bad for an out-of-practice Associate Editor, I tell myself. Two laps later, my self-congratulations are interrupted when Turkington overtakes me on the brakes. Damn! I stick on Turkington’s tail for another lap, taking a look up the inside entering Turn One, but he runs it in deep and it seems too risky a pass, so I ease off. Sadowski, charging from behind, > sees it differently, though, and puts a clean pass on me, sliding into position behind Turkington. Now I’m back to sixth place. Two turns later, an on-thegas Sadowski stuffs it past Turkington in the fast esses and snatches fourth place-why hadn’t I tried that?

We maintain the same running order for the next two laps, but as we come onto the back straight for the final time, I scrunch up to make myself as aerodynamic as possible and play the draft for all it’s worth. Careful not to pass too soon and give Turkington the opportunity to re-take me on the brakes as he’d done previously, I pull out of the slipstream as we run through Gravity Cavity, then wait just

a moment longer when Turkington pops upright from behind the windscreen and applies the brakes. I slip by and never look back until I’ve crossed the line in fifth place.

Ahead of all this slicing and dicing were the top three finishers, Kurt Hall, Donald Jacks and Michael Martin. In fact, for Hall, a 31-year-old from Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, the 600-class victory would be the start of a very successful day. He went on to win the 750 and 1100 finals, the first rider in Cup-racing history to make a clean sweep, pocketing some $15,000 in the process.

Hall, an organizational manager for the Western Eastern Roadrace Association, is a six-time WERA national endurance champion riding for Team Suzuki Endurance, and has been racing a 250cc GP-style two-stroke with success, but currently has no aspirations of going AMA Superbike racing.

“I don’t have a lot of natural talent, so I need seat time to keep my skills up,” Halls says modestly. “With the WERA Pro Series and the Suzuki Cup regionals, I can race almost every weekend. I get more track time, and make as much if not more than most Superbike racers.”

Adding up regional and Final winnings, Hall took home $26,400 in

Suzuki Cup money alone.

“Look, I’d be doing this whether it paid contingency or not,” says Hall. “But the Suzuki Cup allows riders to put back into their pockets some of what it takes to go racing. And it pays farther down the finishing order than other contingency programs: You don’t have to be a national-caliber rider to recoup some of your expenses.”

Asked if he will defend his trio of Suzuki Cup titles in 1993, Hall says slyly, “Oh, I’ll definitely be back.”

SUZUKI CUP RESULTS

GSX-R600 Final

1 .Kurt Hall

2. Donald Jacks

3. Michael Martin

4. Dave Sadowski

5. Don Canet

GSX-R750 Final

1 .Kurt Hall

2. Britt Turkington

3. Donald Jacks

4. Robert Wright

5. Tom Wilson

GSX-R1100 Final

1 .Kurt Hall

2.Donald Jacks

3.Stevie Patterson.

4. Robert Wright

5. Tray Batey

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOr Best Offer

February 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Ducks of Autumn

February 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCComputers Vs. Intuition

February 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupIndian Wars Continue

February 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupOxygenated Fuel And the Motorcyclist

February 1993 By Kevin Cameron