LEANINGS

Room at the inn

Peter Egan

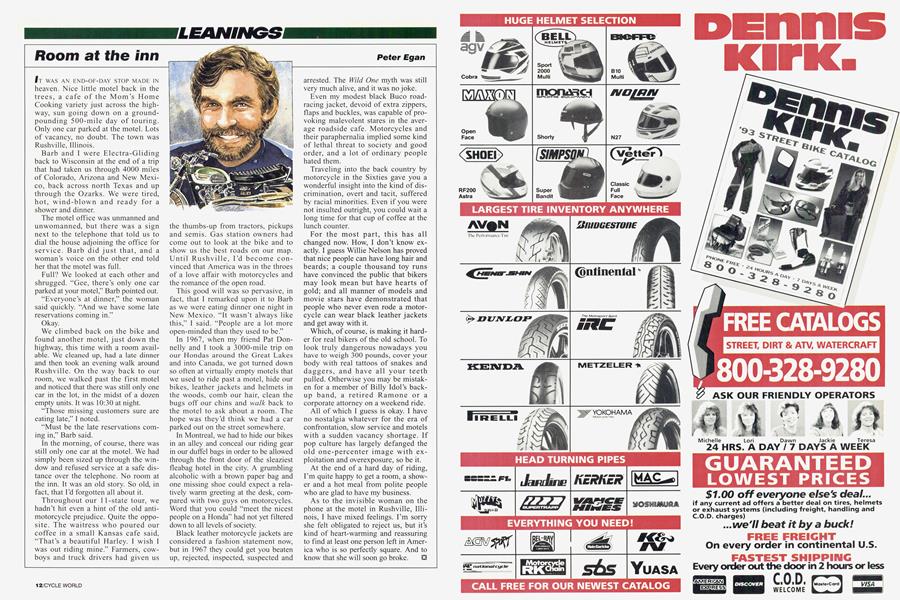

IT WAS AN END-OF-DAY STOP MADE IN heaven. Nice little motel back in the trees, a cafe of the Mom’s Home Cooking variety just across the highway, sun going down on a ground-pounding 500-mile day of touring. Only one car parked at the motel. Lots of vacancy, no doubt. The town was Rushville, Illinois.

Barb and I were Electra-Gliding back to Wisconsin at the end of a trip that had taken us through 4000 miles of Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico, back across north Texas and up through the Ozarks. We were tired, hot, wind-blown and ready for a shower and dinner.

The motel office was unmanned and unwomanned, but there was a sign next to the telephone that told us to dial the house adjoining the office for service. Barb did just that, and a woman’s voice on the other end told her that the motel was full.

Full? We looked at each other and shrugged. “Gee, there’s only one car parked at your motel,” Barb pointed out.

“Everyone’s at dinner,” the woman said quickly. “And we have some late reservations coming in.”

Okay.

We climbed back on the bike and found another motel, just down the highway, this time with a room available. We cleaned up, had a late dinner and then took an evening walk around Rushville. On the way back to our room, we walked past the first motel and noticed that there was still only one car in the lot, in the midst of a dozen empty units. It was 10:30 at night.

“Those missing customers sure are eating late,” I noted.

“Must be the late reservations coming in,” Barb said.

In the morning, of course, there was still only one car at the motel. We had simply been sized up through the window and refused service at a safe distance over the telephone. No room at the inn. It was an old story. So old, in fact, that I’d forgotten all about it.

Throughout our 11-state tour, we hadn’t hit even a hint of the old antimotorcycle prejudice. Quite the opposite. The waitress who poured our coffee in a small Kansas cafe said, “That’s a beautiful Harley. I wish I was out riding mine.” Farmers, cowboys and truck drivers had given us

the thumbs-up from tractors, pickups and semis. Gas station owners had come out to look at the bike and to show us the best roads on our map. Until Rushville, I’d become convinced that America was in the throes of a love affair with motorcycles and the romance of the open road.

This good will was so pervasive, in fact, that I remarked upon it to Barb as we were eating dinner one night in New Mexico. “It wasn’t always like this,” I said. “People are a lot more open-minded than they used to be.”

In 1967, when my friend Pat Donnelly and I took a 3000-mile trip on our Hondas around the Great Lakes and into Canada, we got turned down so often at virtually empty motels that we used to ride past a motel, hide our bikes, leather jackets and helmets in the woods, comb our hair, clean the bugs off our chins and walk back to the motel to ask about a room. The hope was they’d think we had a car parked out on the street somewhere.

In Montreal, we had to hide our bikes in an alley and conceal our riding gear in our duffel bags in order to be allowed through the front door of the sleaziest fleabag hotel in the city. A grumbling alcoholic with a brown paper bag and one missing shoe could expect a relatively warm greeting at the desk, compared with two guys on motorcycles. Word that you could “meet the nicest people on a Honda” had not yet filtered down to all levels of society.

Black leather motorcycle jackets are considered a fashion statement now, but in 1967 they could get you beaten up, rejected, inspected, suspected and

arrested. The Wild One myth was still very much alive, and it was no joke.

Even my modest black Buco roadracing jacket, devoid of extra zippers, flaps and buckles, was capable of provoking malevolent stares in the average roadside cafe. Motorcycles and their paraphernalia implied some kind of lethal threat to society and good order, and a lot of ordinary people hated them.

Traveling into the back country by motorcycle in the Sixties gave you a wonderful insight into the kind of discrimination, overt and tacit, suffered by racial minorities. Even if you were not insulted outright, you could wait a long time for that cup of coffee at the lunch counter.

For the most part, this has all changed now. How, I don’t know exactly. I guess Willie Nelson has proved that nice people can have long hair and beards; a couple thousand toy runs have convinced the public that bikers may look mean but have hearts of gold; and all manner of models and movie stars have demonstrated that people who never even rode a motorcycle can wear black leather jackets and get away with it.

Which, of course, is making it harder for real bikers of the old school. To look truly dangerous nowadays you have to weigh 300 pounds, cover your body with real tattoos of snakes and daggers, and have all your teeth pulled. Otherwise you may be mistaken for a member of Billy Idol’s backup band, a retired Ramone or a corporate attorney on a weekend ride.

All of which I guess is okay. I have no nostalgia whatever for the era of confrontation, slow service and motels with a sudden vacancy shortage. If pop culture has largely defanged the old one-percenter image with exploitation and overexposure, so be it.

At the end of a hard day of riding, I’m quite happy to get a room, a shower and a hot meal from polite people who are glad to have my business.

As to the invisible woman on the phone at the motel in Rushville, Illinois, I have mixed feelings. I’m sorry she felt obligated to reject us, but it’s kind of heart-warming and reassuring to find at least one person left in America who is so perfectly square. And to know that she will soon go broke. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

November 1993 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

November 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

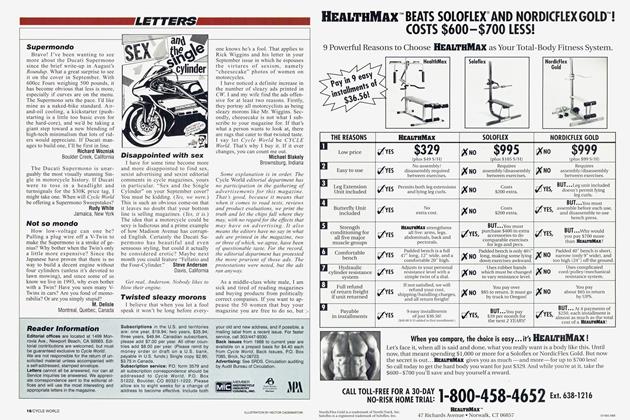

LettersLetters

November 1993 -

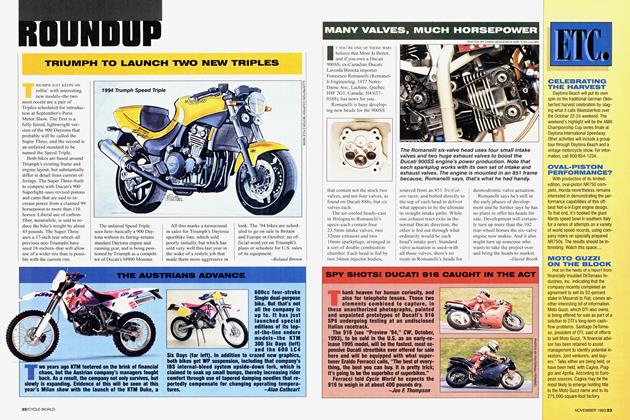

Roundup

RoundupTriumph To Launch Two New Triples

November 1993 By Roland Brown -

Roundup

RoundupThe Austrians Advance

November 1993 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupMany Valves, Much Horsepower

November 1993 By David Booth