GOODMAN H·D·S

Britbike with a heart of American iron

ROLAND BROWN

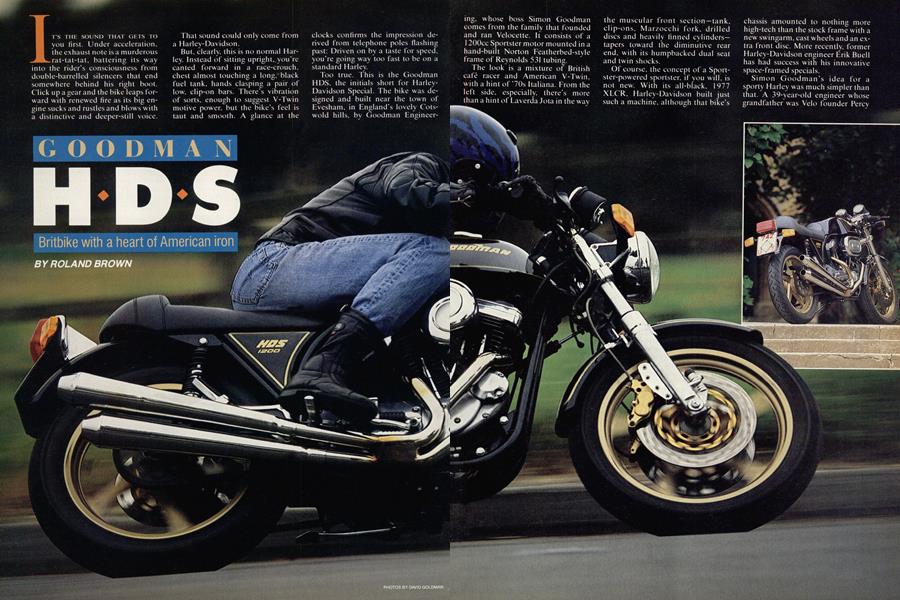

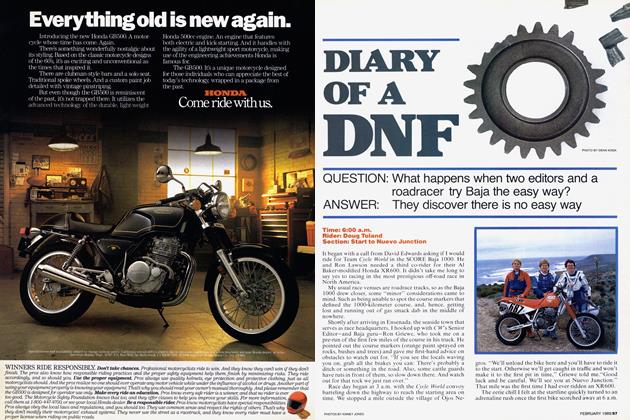

IT'S THE SOUND THAT GETS TO YOU first. Under acceleration, the exhaust note is a murderous rat-tat-tat, battering its way into the rider's consciousness from double-barrelled silencers that end somewhere behind his right boot. Click up a gear and the bike leaps forward with renewed fire as its big engine sucks and rustles and blows with a distinctive and deeper-still voice.

That sound could only come from a Harley-Davidson.

But, clearly, this is no normal Harley. Instead of sitting upright„you’re canted forward in a race-crouch, chest almost touching a long, black fuel tank, hands clasping a pair of low, clip-on bars. There’s vtoration of sorts, enough to suggest V-Twin motive power, but the bike’s feel is taut and smooth. A glance at the

clocks confirms the impression derived from telephone poles flashing past: Driven on by a taste for speed, you’re going way too fast to be on a standard Harley.

Too true. This is the Goodman HDS, the initials short for HarleyDavidson Special. The bike was designed and built near the town of Evesham, in England's lovely Cotswold hills, by Goodman Engineer ing, whose boss Simon Goodman comes from the family that founded and ran Velocette. It consists of a 1200cc Sportster motor mounted in a hand-built Norton Featherbed-style frame of Reynolds 531 tubing.

The look is a mixture of British café racer and American V-Twin, with a hint ot '70s Italiana. From the left side, especially, there's more than a hint ol Laverda Jota in the wav the muscular front section —tank, clip-ons, Marzocchi fork, drilled discs and heavily finned cylinders— tapers toward the diminutive rear end, with its humpbacked dual seat and twin shocks.

Of course, the concept of a Sportster-powered sportster, if you will, is not new. With its all-black, 1977 XLC'R, Harley-Davidson built just such a machine, although that bike's chassis amounted to nothing more high-tech than the stock frame with a newswingarm, cast w heels and an extra front disc. More recently, former Harley-Davidson engineer Erik Buell has had success with his innovative space-framed specials.

Simon Goodman’s idea for a sporty Harley was much simpler than that. A 39-year-old engineer whose grandfather was Velo founder Percy Goodman and whose father Bertie also headed the firm, Simon grew up around bikes and was managing director of BSA before leaving last year to concentrate on his own business, Goodman Engineering Ltd. (Westwood, Buckle Street, Honeybourne, Evesham, Worcestershire, England WRl l 5QQ; telephone Ol l-44-386832090; FAX 831614).

Velocette produced the odd street racer in its time, notably the 500cc Venom Thruxton Single in the ’60s, and Goodman wanted to retain that appeal. “Eve always thought the classic British café racer was one of the best-looking machines ever made,” he says, wistfully.

The answer was close at hand because, although most of Goodman’s eight-strong work force is employed on industrial subcontracting, one successful sideline is the production of replica Norton Featherbed frames. The HDS frame retains the Featherbed look: Twin front tubes split on the way down, run beneath the engine and then curve back upwards with a distinctive loop in front of the sidepanels. The hefty Harley motor did require Goodman to produce an enlarged version of his normal frame, bronze-welded in the same 1.25inch-diameter, 16-gauge Reynolds tubing, but beefed-up in the steeringhead and swingarm-pivot areas.

“We started from scratch, keeping the Featherbed lines,” he says. “It had to be much stronger because the original had a tendency to nod its head, and it wasn’t designed to stand the braking force from two massive, great discs.” The swingarm is made from oval-section 531 tubing, with chain-adjustment facilities at the pivot, says Goodman, “because it’s stronger that way.”

It would be all too easy to despair of ever taming the dreaded Sportster shakes. But when Goodman conceived the idea for a Featherbedframed Harley-Davidson special, he brought to the table the confidence that its vibration could be controlled by using Metalastik bushings—each basically a steel sandwich containing a small piece of insulating rubber.

With the chassis taken care of, a suitably mean-looking sportbike was sketched out, then —after being shown to a few friends for comments—drawn up on a computer screen by Goodman and engineer Martyn Roberts (a member of the team that designed the new Triumphs). The neat black-and-gold prototype, 18 months in the making, is remarkably faithful to that original artist’s impression.

The 5.2-gallon, steel fuel tank and the humped seat were dispatched to local suppliers for manufacture. The seat is an example of traditional British craftsmanship, a blend of fiberglass base and genuine Connolly hide cover. “It’s done by a friend who’s an antique furniture restorer,” grins Goodman. “Using leather gives us lots of problems, but nice touches are what people want on a bike like this.”

One of Goodman’s responsibilities at BSA—which these days produces a dual-purpose model with a BSA-built frame and a 175cc Yamaha DT engine-had been dealing with Italian parts suppliers, so that country was the obvious choice for outfitting the HDS. He prefers not to name individual suppliers. “Most of the stuff is made to our design; you can't just buy it off the shelf anymore,” he says. But there’s no concealing the rebound-damping-adjustable 42mm Marzocchi fork, nor the distinctive, four-piston Brembo calipers that bite on floating, 1 1.8-inch discs.

Also of Italian origin are the magnesium wheels, 18-inchers at each end, and in the prototype’s case, fitted with Avon Super Venoms in 110/ 90 front, 130/80 rear sizes. Twin Koni shocks complete a spec sheet that would have been state-of-the-art a decade or so ago. Many other parts, including the triple clamps, clip-ons, adjustable footrests and aluminum engine-plates (which hold Metalastik bushes at each of the 10 mounting points) are designed and built by Goodman, as is the tuneful, twin-silencer exhaust system.

Harley-Davidson’s contribution restricted to instruments, a few electrical parts and the all-important motor. Goodman can supply the HDS as either a chassis kit or as a finished bike; export prices are £5995 (about $10,000) without engine, or £8700 (about $14,800) for a ready-to-roll, five-speed 1200, complete with paintwork and powder-coated frame in any color you like. Goodman hopes he’ll soon be building them at a rate of 100 per year.

He’s also happy to give the motor tweak. The one propelling the prototype is a four-speed 1200 benefiting from Screamin’ Eagle cams and ignition, plus a larger-than-stock, 40mm Keihin carb. The bulky air-filter cover jutting out by the rider’s right knee is standard, though, and along with the H-D instruments are the rider’s only visual reminders, as he reaches forward to the bars, of the bike’s American connection. If anything, the bike seems more like an old air-cooled Ducati, but the 45-degree motor has quite a different feel than any 90-degree Duck engine as you fire it up, prod home the tall first gear and gallop off.

The juices take a couple of miles to warm up, but after that, the Keihin carburâtes crisply and the engine pulls with all the low-rev punch you’d expect of a breathed-on Twin displacing 1200cc. Even this hottedup Harley is probably not making much more than 60 horsepower, but peak torque (71.5 foot-pounds) on the stocker arrives at just 4000 rpm, and the Goodman puts out plenty of grunt even at half that figure.

Roll the Keihin open at anything above 40 mph in top gear, and the HDS charges forward eagerly and with surprising smoothness. Apparently, the Metalastik system really does work, calming most of the stock Sportster’s judders until the revs get above about 4300 rpm, at which point the dancing pistons make their presence felt through bars and seat. The tuned test bike’s tall gearing meant that by the time it was turning 4300 rpm it was traveling at more than 80 mph, so for backroad riding, the HDS was comfortable as well as respectably quick.

But what’s especially impressive is that the bike handles like no other Harley I’ve ridden, combining solid feel with easy steering, thanks to firm suspension and distinctly un-Harleylike rake-and-trail figures of 26 de-

grees and 3.2 inches. The Konis were too firm even for my 200 pounds, but they still provided a massive improvement on the stock Sportster’s short-travel shocks.

The Marzocchi fork proved well up to the job, even if a couple of times it transmitted the slightest of headshake; generally, it kept the bike pointed exactly where it was aimed. The brakes were brilliant, the Avons very competent, and despite being no lightweight at 450 pounds (20 less than stock), the 1200 could be thrown around with confidence.

On a straight stretch leading back to Goodman's base, nearing the conclusion of my short test ride, the HDS touched an indicated 120 mph, and would doubtless have gone slightly faster given more space. But by then, the vibes had set in, the engine was sounding strained and the lack of fairing was adding to the discomfort. Best to slow down, find a twistier road, and enjoy the grunt and the ground clearance in the top-gear sweet zone between 40 and 85 mph.

Even this sportiest of Sportsters has distinct performance limits. Indeed, Simon Goodman is the first to accept that his creation is no bike for sustained three-figure speeds.

But forget the limits. The Goodman HDS is handsome, well-made, distinctive. On the right road, this fast and very entertaining motorcycle is not at all bounded by conventional limitations. It’s a unique blend of European and American engineering that helps you understand just how special a Special can be. s

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

March 1992 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

March 1992 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

March 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1992 -

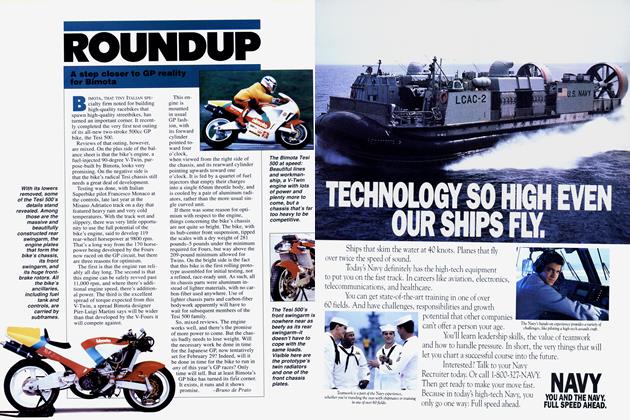

Roundup

RoundupA Step Closer To Gp Reality For Bimota

March 1992 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupAmerica 1: Gold-Plated Superbike

March 1992 By Jon F. Thompson