CYCLE WORLD TEST

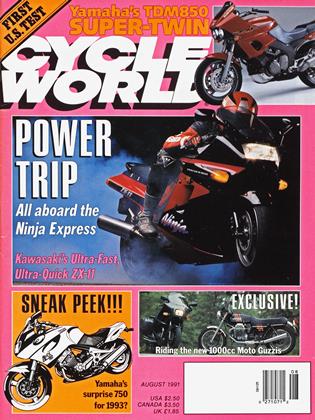

KAWASAKI ZX-11

ON A SCALE OF 1 TO 10, THIS ONE'S AN 11

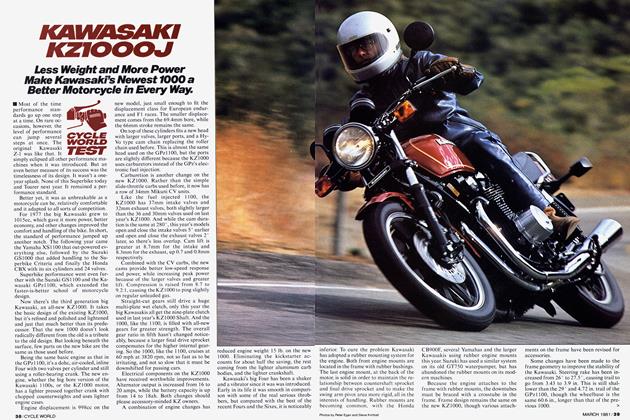

THE EVIDENCE WAS IRREFUTABLE. As SOON AS WE SAW the telltale black stripes in the parking lot, as soon as we saw the dark streak Whoosh past our windows, we knew. It was back. The ZX-11. That jet without wings that transforms everyone who climbs aboard it into Jay Gleason. Or Don Vesco. Or God.

Now two years old, the Kawasaki ZX-11 Ninja is still the baddest, meanest, flat-nastiest motorcycle available. Forget about the other big-bore sportbikes: They're ail slow. The ZX-1 1 w'axes the fastest of them—the 163-mph Yamaha FZR1000—by a whopping I I mph. To go any faster than the 174 mph our ZX-1 1 clocked, you'll need aur wheels. Or a flight plan. And you'd have to spend a money than the Ninja's $7999 asking price, does the ZX-1 1 go so darn fast? The traditional way, with a combination of sheer horsepower-an estimated 145-and aerodynamics. Its fully encompassing bodywork includes a flush-mounted headlight, fin-like protrusions that house the turnsignals, and a huge fender that wraps around the front tire, splaying at its rearward edge to funnel air across the fairing’s surface.

But there's a twYst. Not only does the ZX-1 1 's bodywork aid its aerodynamics, it also plays a part in the motor's power production. In the 1970s, Ram Air was a phrase coined by Suzuki to describe the shrouds that routed cooling air over its two-strokes’ cylinder heads. These days, Kawasaki uses the term to describe its air-induction system. Simply put, the system draws air through a scoop below the headlight and routes it through an elaborate snorkel to a huge airbox beneath the fuel tank. It is the airbox’s sole source of oxygen. The incoming stream pressurizes the airbox. forcing air into the bank of four 40mm Keihin semi-flat-slide carburetors, and the resultant fuel mixture then rushes through the hand-polished intake ports into the combustion chambers.

In order to match the fuel supply to the variable air pressure, the carbs' float bowls vent through a single hose that runs up to the front of the air scoop, where incoming air pressurizes the float bowls in the same manner as it does the airbox.

The result is that the faster the ZX-1 1 goes, the more horsepower its dohc, 16-valve inline-Four motor produces. Which is a lot. because the ZX-1 1 's engine is based

on the one used in the ZX-10—no average performer in its own right—with a number of changes. There’s 55cc more displacement, thanks to a 2mm-larger bore; 2mm-larger carburetors; lighter, concave pistons, which in conjunction with the narrow, 30-degree included valve angle produce a spherical combustion chamber; bigger valves; longer-duration cams; and chrome-moly connecting rods that bolt to larger crankpins.

Those interested in doing their own maintenance will be happy to know that valve clearances can be set with the cams still m the heads, thanks to the use of individual linger followers that are spring-loaded on their shafts and can be slid out of the way to allow for shim replacement.

To keep operating temperatures out of the red zone, a huge, curved radiator tills the space behind the front wheel, while a small oil cooler resides just beneath. Exhaust gases exit through a large-volume. 4-into-1-into-2 system, which is extremely quiet, not only for a bike as powerful as the ZX-1 l. but for a bike of any size.

Transferring the Ninja’s awesome power to the rear wheel is a hydraulically actuated wet clutch, with thicker, larger-diameter plates than on the old ZX-IO, and radially grooved drive plates that improve oil flow for increased cooling and resistance to fading. The slick-shifting sixspeed transmission uses the same internal ratios as the ZX10, but second through fourth gears were made stronger and the primary drive ratio was raised a bit.

With all that power on tap. one would imagine the ZXl l would be an animal to ride. But in reality, it's a sweetheart. smooth at anything above 2500 rpm thanks to a counterbalancer that dampens vibration. If you can muster the restraint to keep the motor in the lower portion of its powerband, you can exploit its vast reserves of torque. Doing the Texas two-step on the shift lever is not a requirement for riding the big Kawasaki, even on a swervy backroad.

The ZX is geared too tall to be a roll-on king, but it's got power—and plenty of it—from just above idle right on up to redline. Carburetion is spot-on, though response can sometimes be too abrupt, causing the bike to lunge forward hard enough to amplify its slight driveline lash. Still, the driveline is not as sloppy as that oí' its smaller sibling, the ZX-6. even in the 6's improved 1991 configuration.

It's when you whack the throttle on, though, that the ZX-l l really grabs your attention. Snick it into first gear, let out the clutch, turn the throttle to the stops and the Ninja Express is on its way. By 7000 rpm, the front wheel is aiming skyward, and if you run the tach to redline in first, you'll see an indicated 70 mph. You could cruise a German autobahn in second gear and still keep up with most trafile. That is, until some wannabe Hans Stuck in an

Audi turbo toyed with you, at which point you'd be obligated to upshift and blow his doors into the stratosphere.

In spite of its incredible motor, the Ninja is capable of f ar more than straight-line performance. Its tw in-spar aluminum frame—widely bowed around the cylinders—and equally massive swingarm are rigid, and well up to the task of harnessing the ZX's megapower output. There are limits, however. Push too hard, fling the bike into a corner, then grab a handful of throttle, and the Ninja spins its giant rear Dunlop Sportmax radial, the bike’s rear end stepping out: Wayne Rainey and the rest of the GP boys have got nothing on a ZX-l 1 owner. Except maybe cornering clearance, and even there, the ZX fares pretty well. Its neutral steering inspires explorations to the outer fringes of traction and lean angle, and though it's no repliracer, the 1 1 doesn't touch much down.

Adding to the Ninja's surefootedness is its suspension — a 43mm, conventional telescopic fork and single, remotereservoir shock, both easily adjustable for spring preload and rebound damping. Adjusting the damping on the fork entails the simple use of a straight-blade screwdriver; preload is altered w ith a 1 7mm wrench. The shock's damping is changed by a knob you can turn by hand, hidden behind a removable plastic cover; its preload uses a threaded collar and locknut, which requires the use of a spanner or the more primitive hammer-and-punch technique to adjust. All but the shock's spring preload can be adjusted with tools provided in the pouch under the removable onepiece seat.

Our test bike arrived with its fork-spring preload set with six of the eight index lines showing, and on the secondsoftest of four rebound-damping settings. That worked well, though after experimenting, we turned the rebound damping up one click. At the rear, we settled on spring preload about halfway up the threaded collar, and set the rebound on the second of the four positions, which turned out to be ideal in all street-riding situations. Only an overabundance of compression damping detracts from the Ninja's ride; at moderate speeds over small bumps, it’s too harsh, resulting in a rough ride. It makes up for that, though, with a supremely composed feeling at speeds more suited to the Bonneville Salt Flats.

Creature comforts aren't something most hardcore sportbikes are known for. but the Ninja iscush city. It has a

smoothly contoured seat with plenty of room for two, adjustable brake and clutch levers for the rider, a grabrai! for the passenger, and the fairing provides excellent protection from the hurricane-like windblast the ZX-l I is capable of producing.

If there's one component of the Ninja we're not impressed with, it's the iront disc brakes. Though the dual, four-opposed-piston Tokico calipers are plenty strong, they fade too easily. Attack a road with a bunch of tight corners—perhaps one punctuated by fast straightaways— and by the end of the ride, your heartbeat will be racing. Similar brakes work flawlessly on the Z.X-7 and ZX-6, but come up short on the l I. The problem lies in the speeds generated by the ZX. and in its weight—58 l pounds w ith a full tank of fuel.

The ZX-1 l isn't the only big bike saddled w ith too much mass. In fact, the elimination of weight seems to be the next front for big-bore sportbikes, as even the Suzuki GSX-R l 100 and Yamaha FZR 1000 have picked up some pounds over the years. As reported in last month's Roundup section, Honda w ill likely have a CBR900RR in 1992. rumored to weigh-in at a feathery 420 pounds dry. Whether that bike will surpass the Kawasaki as the new absolute king of speed remains to be seen.

In the meantime, the ZX-l l still reigns, even if it is two years old and unchanged. Well, there is one difference: The 1991 ZX-l l now comes in what Kawasaki's marketing types unashamedly call an “ebony/luminous rose opera" color scheme. Hype aside, the paint job is more dramatic than last year's all-black, so that the bike now looks fast at a standstill, too.

Which, if you're riding anything else, may be the only way you'll ever see it. E2

KAWASAKI

ZX-11

$7999

EDITORS' NOTES

DRAWING ON MY MANY HOURS OF P1lot training. I concentrate on settin' her down easy. Due to a high angle of attack, nothing but blue sky fills the windscreen. Pushing 100 knots per hour. it becomes increasingly diffi cult to maintain the nose-high atti tude. As she begins to stall, I apply more throttle, but she's already at full burn and the nose drops to the horizon. The tire lets out a wail and a puff of blue smoke as the landing gear absorbs the impact of the front wheel hitting the deck.

Oh well, another aborted run through the Carlsbad timing lights.

Keeping both wheels grounded. the skipper tells me. is the key to turning low ETs in the quarter-mile. But that's a tall order when flying a Kawasaki ZX-I 1 through the clocks. And not nearly as much fun, either.

I probably won't ever get a chance to shoot a carrier landing in an F-14 Tomcat. As long as I can get some stick time in the cockpit of a ZX-l I. though, I won't be too disappointed. -Don Canet. Associate Editor

LISTEN: IT'S A GOOD THING WE'VE reached adulthood, and no longer are graded on such things as citizenship. I wouldn't fare very well, not with the ZX-1 I around.

Oh, it's a long way from being my favorite motorcycle. I'd prefer some thing with a more padded seat and a less stiff-legged ride, something that weighs less and doesn't so easily smoke its brakes. But never mind comfort and balance. The ZX~ 11 has

That Engine, and the power it churns out makes it very difficult to win citizenship awards. When I ride it, I hear it goading me, "Come on, come on! We can go a lot faster." Indeed. I suppose I'm predisposed toward this sort of temptation. At least I've been lucky: I haven't been tossed in jail for speeding. Not yet, anyway. Is that because I've been wearing my old Good Citizenship pin on my leathers? -Jon F Thompson. Feature Editor

IN MV THREE-AND-A-HALF-YEAR CA reer as a motojournalist. there have been a few motorcycles that stand out as personal milestones. I remem ber the first one well, a 1988 Kawa saki ZX-lO. It was a big bike. pretty heavy, too, `but it was the fastest streetbike in the world. Then I heard about the ZXI 1. "It's a V-Max that handles," the rumors said.

Sounded like the ZX-lO to me. Boy, was I wrong. Although the ZX11 is the same size and a few pounds heavier than the ZX-1O. it somehow feels smaller and lighter. And it seems so much faster that i(s almost unbelievable. But what really seems im possible is how mild-mannered the ZX1 I is. If you can spore the little devil on your shoulder chiding you to `Gas it," you'll find that it's an extremely civilized streetbike.

We all like to fantasize about going just shy of 200 mph, but in real-world riding, it's civility that counts. The ZX-1 l's got it in spades. -Brian Catierson, Managing Editor

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

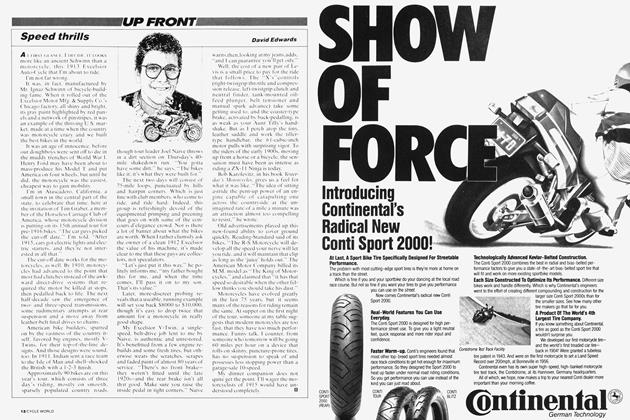

Up Front

Up FrontSpeed Thrills

August 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeStatus Miles

August 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

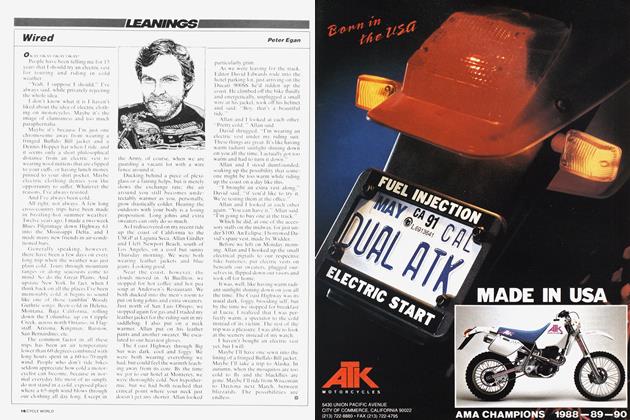

Leanings

LeaningsWired

August 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupNorton In Trouble, Cagiva To the Rescue?

August 1991 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupMove Over Rolls, Hesketh's Back

August 1991 By Alan Cathcart