Soichiro Honda, 19061991

KEVIN CAMERON

The man behind the machines

SOICHIRO HONDA HAS DIED AT age 84 after a remarkable life. His name is known evcrywhere today as that of a man who created in 25 years a manufacturing empire as powerful as any in the world. It is correct to say that he Was rude, unconventional, difficult and an extremely original thinker. T his is all the more remarkable when we recall that he was born in a nation that reveres formality and tradition. Soichiro Honda burst the bonds of traditional Japanese life, never fearing to offend anyone, never giving up an idea because experts said it wouldn't work, always respecting people, not for their degrees or positions, but for their originality and character.

Born a blacksmith's son in I 906, Honda entered an impossibly split world: private life went on in the mannered wavs of medieval Japan, but industry was fast changing everything else. As a boy, Honda was intoxicated by the strangeness and power of the first automobile he saw. Later on. he did an unthinkable thing, disobeying his father to travel to a nearby tow n —to see an airplane. It would not be the last time he broke with tradition to follow his ow n path.

Moving to a faraway city to work in the auto trades, Honda lived through a numbing apprenticeship, unable to show his special understanding of machines. But when the Tokyo earthquake of 1923 hit, real talent was suddenly more valuable than seniority. Honda was quickly made branch manager. Machines made sense to Honda, and he was soon able to live well and drink deep of life’s pleasures.

It wasn't enough. I londa wanted to build his own ideas. At first, this meant constructing and racing automobiles. but even this was simply Tinkertoys to his powerful imagination. Brashly. he entered the pistonring business, but discovered quickly that raw enthusiasm and a knack with machines wasn't enough. The business came close to failure, but I londa rescued it by finding people who understood metallurgy and casting, and by experimenting relentlessly.

Then came the war. ending in devastation. It is now legend how Honda bought surplus generator engines, attached them to bicycles, and sold cheap, basic transportation. With gasoline strictly rationed, he and his few employees made a turpentinelike fuel for their customers—out of evergreen tree roots.

Honda Motor Company rose above its many competitors by constant improvement and creative marketing. The primitive generator engine was replaced by better Honda designs. Honda franchised dealers all over Japan in an era when motorbike brands were only sold locally. The Korean War pumped capital into Japan's economy, but the war's end brought recession. Honda somehow survived it. Many other motor companies did not.

Racing was always central to Honda’s marketing, but success was slow to come. The company struggled with racing’s special problems until success came—first in Japanese national racing. In emphasizing the importance of racing, Honda was surely recalling the power of the excitement he had felt as a boy. seeing his first self-propelled machines.

In 1954, Honda took another great step; he left Japan to tour Europe’s motorcycle and machine-tool producers. He wanted to know what the world standard was in these areas, and what he learned was hard to swallow. The most powerful Honda 25()cc engine developed only onethird the power of similar-sized German engines.

Honda knew the power of research and development; he had saved his piston-ring enterprise by finding correct answers in a sea of wrong ones. Through research and development, his products would achieve high quality. Through marketing, Honda would become a household word, lo establish the name, he set an ambitiousgoal: to defeat the best motorcycles in the world at the Isle of Man TT roadraces. At this time. Japan was derided in Western countries as a maker only of toys and cheap cameras. Westerners laughed at Japanese engineering, calling it uncreative copying.

Honda proved otherwise. I lis company equalled the power of European racers by 1959. then outpowered them decisively in 1962, when the Honda factory team won its first 250cc world championship. Honda personally attended the presentation ceremony and told the world it could no longer dismiss Japan as "d nation of copyists." I low' right he was.

Having launched his company on post-war demand for transportation, Honda needed a new market. He would create it. Motorcycles had been sold as cheap wheels, a substitute for a car. but Honda had seen the West and knew of its affluence and leisure. He would sell motorcycles to Americans, and they would ride them because it was fun. We did. The coming of Honda motorcycles to America created the biggest motorcycle market ever known—and it created a generation of riders who have kept motorcycling in their lives ever since.

Even as this market was expanding, Honda entered the automobile business. Early models failed to click with the U.S. market, but the coming of the Civic coincided with the first oil crisis. Small, economical and reliable, the Civic made Honda owners of millions more Americans. More sophisticated models followed. By the 1980s, Honda Motor Company was recognized as one of the most powerful and innovative auto makers in the world.

In the production of motorcycles, Honda showed the world that high quality in a sophisticated product need not be expensive. Honda models brought to market features previously found only in factory racing machines: overhead camshafts, multiple valves, liquid-cooling. His factories showed that rational production methods—not cheap labor—were the key to all this. When Honda automobile and motorcycle factories were built here in the U.S.. high quality and reasonable price continued to be achieved with highly paid American industrial workers.

Honda always emphasized that failure is an essential ingredient of success. If you haven't the stomach to push confidently through failure, eliminating the wrong answers one by one, you will never succeed. Only through this creative struggle can success be reached.

Despite his position, Honda was never a remote figure locked away in a boardroom. He wore the company cap and jacket or coveralls when he joined in problem-solving sessions on the factory floor—and when he attended meetings with high government officials. He believed that work, not clothing, gave dignity.

He was impatient with muddled or stereotyped thinking. There is a story of his having entered a lab where two technicians were struggling to remove the cylinder head from a prototype machine: it w;as too close to the frame. Honda helped with the removal, then summoned the engineer responsible. When the frightened man arrived, he had to duck a flying cylinder head, personally hurled by the president.

After his retirement in 1973, his presence and influence continued much as before. When the Gold Wing touring bike was in development, he quietly appeared one night at the test track, where under bright lights, an untried prototype was being readied for the morrow’s testing. Without a word, he eased the heavy machine off its stand, and rode smiling into the darkness. Returning some hours later, to the great relief of apprehensive employees, he parked the machine, sai, “Pretty good,” and went home.

Throughout his long and creative life, Honda went his own way. But it w'as our way, too. We who are motorcycle enthusiasts share the wonder and excitement of that little boy, so long ago, who ran after the first motorcar he had seen. We are fortunate that he had the combination of fascination, unconventionality, patience and knowledge to give those powerful feelings solid form in the machines we have enjoyed so much.

Thank you. Soichiro Honda. S3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Norton Girl And Other Tragedies

November 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeNone Dare Call It Progress

November 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsReplacements

November 1991 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUpheavals

November 1991 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1991 -

Roundup

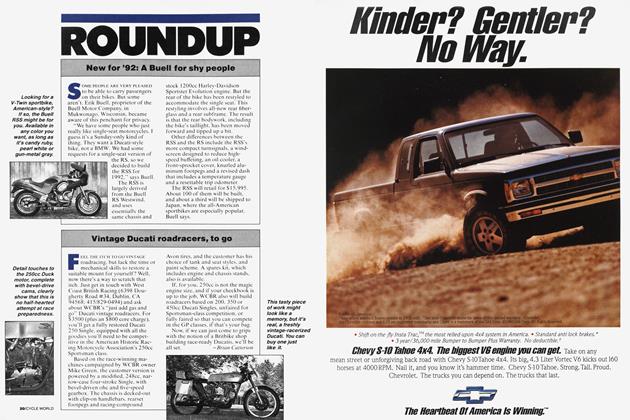

RoundupNew For '92: A Buell For Shy People

November 1991