Death of the fork?

UP FRONT

David Edwards

I HAVE SEEN THE FUTURE, AND I’M NOT

so sure about it.

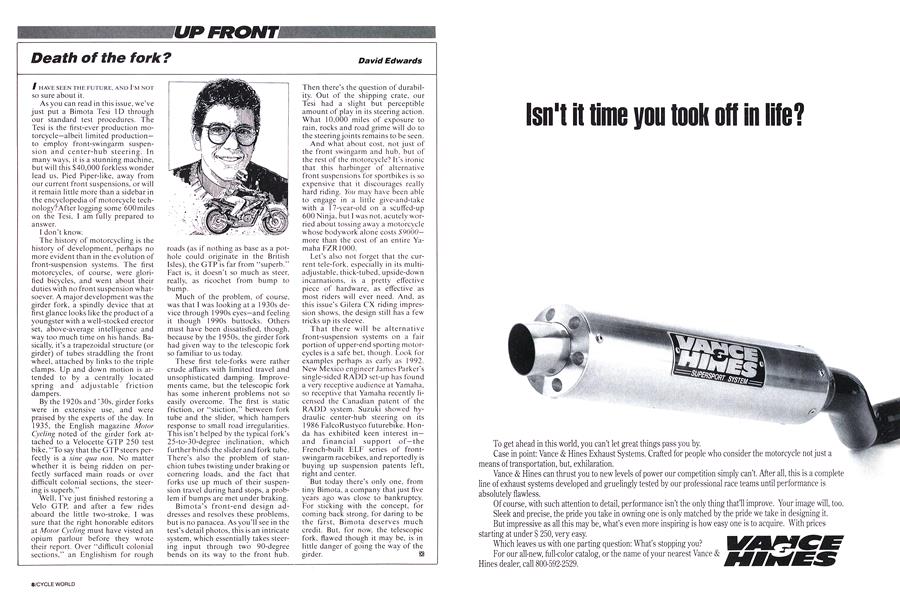

As you can read in this issue, we’ve just put a Bimota Tesi 1D through our standard test procedures. The Tesi is the first-ever production motorcycle—albeit limited production — to employ front-swingarm suspension and center-hub steering. In many ways, it is a stunning machine, but will this $40,000 forkless wonder lead us. Pied Piper-like, away from our current front suspensions, or will it remain little more than a sidebar in the encyclopedia of motorcycle technology?After logging some óOOmiles on the Tesi, I am fully prepared to answer.

I don't know.

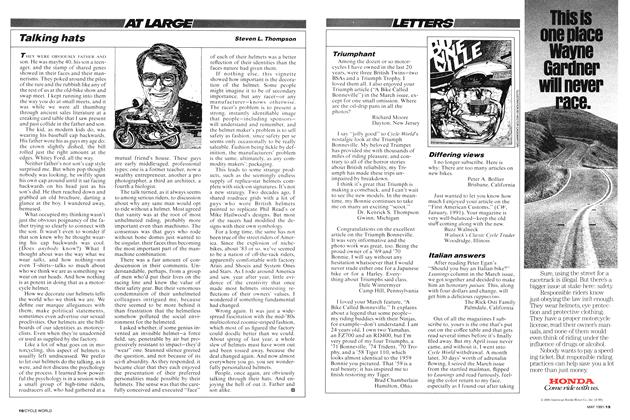

The history of motorcycling is the history of development, perhaps no more evident than in the evolution of front-suspension systems. The first motorcycles, of course, were glorified bicycles, and went about their duties with no front suspension whatsoever. A major development was the girder fork, a spindly device that at first glance looks like the product of a youngster with a well-stocked erector set, above-average intelligence and way too much time on his hands. Basically, it’s a trapezoidal structure (or girder) of tubes straddling the front wheel, attached by links to the triple clamps. Up and down motion is attended to by a centrally located spring and adjustable friction dampers.

By the 1 920s and '30s, girder forks were in extensive use, and were praised by the experts of the day. In 1935, the English magazine Motor Cycling noted of the girder fork attached to a Velocette GTP 250 test bike, “To say that the GTP steers perfectly is a sine qua non. No matter whether it is being ridden on perfectly surfaced main roads or over difficult colonial sections, the steering is superb.”

Well, I’ve just finished restoring a Velo GTP, and after a few rides aboard the little two-stroke, I was sure that the right honorable editors at Motor Cycling must have visted an opium parlour before they wrote their report. Over “difficult colonial sections,” an Englishism for rough

roads (as if nothing as base as a pothole could originate in the British Isles), the GTP is far from “superb.” Fact is, it doesn’t so much as steer, really, as ricochet from bump to bump.

Much of the problem, of course, was that I was looking at a 1930s device through 1990s eyes—and feeling it though 1990s buttocks. Others must have been dissatisfied, though, because by the 1 950s, the girder fork had given way to the telescopic fork so familiar to us today.

These first tele-forks were rather crude affairs with limited travel and unsophisticated damping. Improvements came, but the telescopic fork has some inherent problems not so easily overcome. The first is static friction, or “stiction,” between fork tube and the slider, which hampers response to small road irregularities. This isn't helped by the typical fork’s 25-to-30-degree inclination, which further binds the slider and fork tube. There’s also the problem of stanchion tubes twisting under braking or cornering loads, and the fact that forks use up much of their suspension travel during hard stops, a problem if bumps are met under braking.

Bimota’s front-end design addresses and resolves these problems, but is no panacea. As you'll see in the test’s detail photos, this is an intricate system, which essentially takes steering input through two 90-degree bends on its way to the front hub.

Then there’s the question of durability. Out of the shipping crate, our Tesi had a slight but perceptible amount of play in its steering action. What 10,000 miles of exposure to rain, rocks and road grime will do to the steering joints remains to be seen.

And what about cost, not just of the front swingarm and hub, but of the rest of the motorcycle? It's ironic that this harbinger of alternative front suspensions for sportbikes is so expensive that it discourages really hard riding. You may have been able to engage in a little give-and-take with a 17-year-old on a scuffed-up 600 Ninja, but I was not, acutely worried about tossing away a motorcycle whose bodywork alone costs $9000— more than the cost of an entire Yamaha FZR1000.

Let’s also not forget that the current tele-fork, especially in its multiadjustable, thick-tubed, upside-down incarnations, is a pretty effective piece of hardware, as effective as most riders will ever need. And, as this issue’s Güera CX riding impression shows, the design still has a few tricks up its sleeve.

That there will be alternative front-suspension systems on a fair portion of upper-end sporting motorcycles is a safe bet. though. Look for examples perhaps as early as 1992. New Mexico engineer James Parker's single-sided RADD set-up has found a very receptive audience at Yamaha, so receptive that Yamaha recently licensed the Canadian patent of the RADD system. Suzuki showed hydraulic center-hub steering on its 1986 FalcoRustyco futurebike. Honda has exhibited keen interest in — and financial support of—the French-built ELF series of frontswingarm racebikes, and reportedly is buying up suspension patents left, right and center.

But today there’s only one, from tiny Bimota, a company that just five years ago was close to bankruptcy. For sticking with the concept, for coming back strong, for daring to be the first, Bimota deserves much credit. But. for now. the telescopic fork, flawed though it may be, is in little danger of going the way of the girder. £3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

At LargeTalking Hats

May 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1991 -

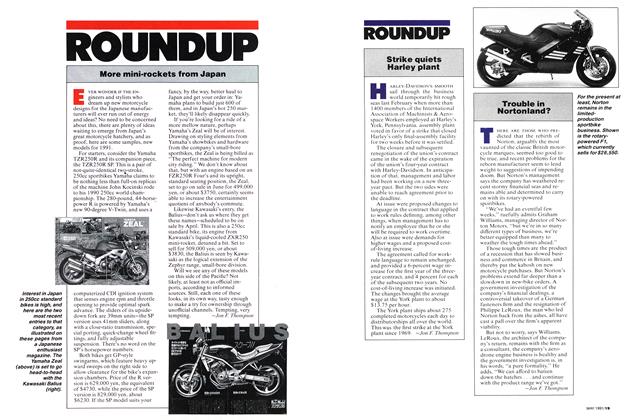

Roundup

RoundupMore Mini-Rockets From Japan

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

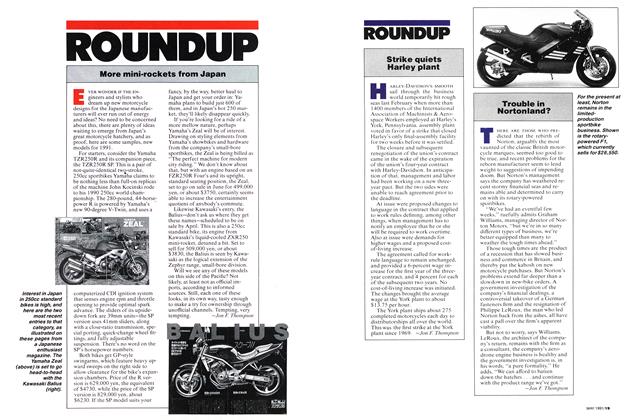

Roundup

RoundupStrike Quiets Harley Plant

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

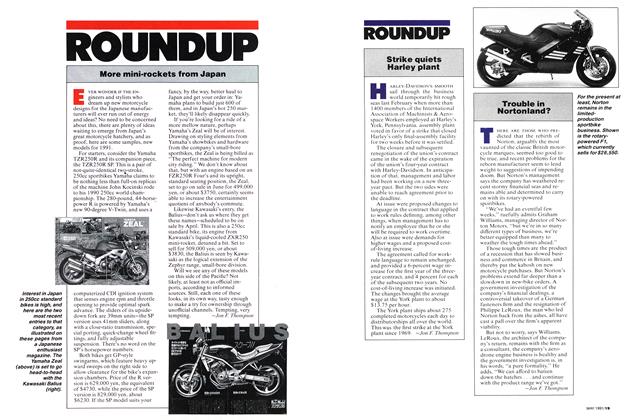

Roundup

RoundupTrouble In Nortonland?

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

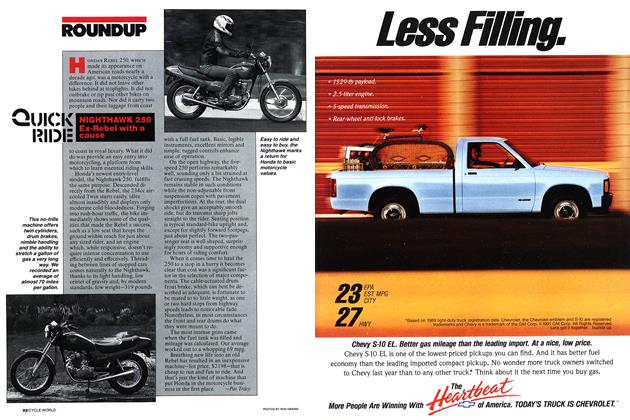

Roundup

RoundupNighthawk 250 Ex-Rebel With A Cause

May 1991 By Pal Tracy