UP FRONT

Going boom

David Edwards

TONY BENNETT SINGS ABOUT LEAVING his heart in San Francisco. Big deal. I left my collarbone in Austin, Texas.

Well, that's not quite true. I went to Austin with two collarbones, and came back with four, my left clavicle snapped in two places.

It was a glory crash, occurring as it did in the last lap of a Twins-class roadrace while I was in the midst of a pass for the lead.The guy in first place took the classic, arching line through a corner. I, adrenal glands at the limit, friends and family in the grandstands, squared the thing off; a strategy that insured his modified lOOOcc Yamaha and my Kawasaki EX500 would cross paths at some point in the corner.

I blinked first. Or rather tried to scrub off speed and avoid the oncoming collision by feathering my front brake while still heeled over. No dice. Metzeier Comp K Lasers are good, but not that good, and dow n I went at about 45 mph. right onto my unsuspecting left shoulder. My collarbone never had a chance.

In 20 years of street and oflf-road riding. I'd never before broken a bone. Sure, there had been bumps, scrapes and bruises, and a stretched knee ligament, but nothing more serious than could have been sustained in a pick-up basketball game between friends.

Collarbones, it turns out, weren't really designed with falling off of motorcycles in mind. Ask almost any racer, they've all got clavicles with abnormal bumps or waves. At least the vulnerable bones seem to knit readily, without the need of a cast. My sports-medicine doctor cinched me into a sling, told me to stay of!' bikes for a few weeks and assured me that the bump in my shoulder would subside somewhat, “though you'd better think twice about a career in porno movies.” Gee, and Mom always told me to have something to fall back on.

Ten days later (sorry. Doc), I was riding again, tentatively at first on a 50cc scooter. Then came streetbikes a week after, and six weeks on, I was in the saddle of an endurance racebike, blasting down Willow Springs’

front straight at a buck fifty and change.

The husband of a friend once spoke to me about riding motorcycles—actually about not riding motorcycles. “I don't know how you guys do it,” he said in earnest tones. “It's just too dangerous for me.” A few months after that pronouncement, he got into his car after drinking too much alcohol, passed out at the wheel and rammed into another car. Months of bone operations and skin grafts and physical therapy have cost $85.000. and he still doesn't have proper use of his legs. Luckily, no one else was injured. And this guy thinks we 're daredevils.

Of course, we've all run into this before. Mothers who won't let their daughters ride with you to the highschool homecoming bonfire because a distant uncle once broke a leg on an old Indian Chief. Medical professionals who corner you at parties and regale you with the latest emergencyroom horror stories about downed motorcyclists. Forgetting, of course, to fill you in on the details of all the auto-accident victims that pass under their scalpels. After all, they and most of the other party-goers, came to the party in automobiles, not on motorcycles.

Not for a second would I try to portray motorcycle riding as being free of risk, of not being without danger. Every rider I've ever known, from

multi-time world champion to million-mile touring man to Vespa-riding co-ed. has taken a tumble. Most falls are minor, skinned-knee-and-elbows sorts of things, no more serious than falling off a bicycle as a kid. Some are more serious, some deadly. There are no guarantees with motorcycling, just as not everyone who climbs into a car for the morning commute gets to work, just as not everyone w ho boards a passenger plane arrives at the other airport.

Motorcycling, you see, is about movement, both physical and spiritual, and whenever you’re moving— whether it be those first halting steps as a child, whether it be along a career path, whether it be in a relationship or whether it be on a motorcycle— there is always risk. People who have stopped taking risks, I’ve found, have stopped moving. In essence, have stopped living.

Not that I expect every citizen of this country to strap on parachute harnesses and start jumping out of airplanes, or go rock-climbing up the face of El Capitan, or even try to shove the nose of a little EX500 underneath a big booming Yamaha at some obscure track in the capital of Texas. Come to think of it, though, that might not be such a bad idea. Probably cut down on hyper-tension, not to mention alcoholism, obesity, per-capita Valium intake and the current outbreak of couch-potatoism.

The racing EX500 is gone now. And missed. I keep photos of it in my desk drawer, and every so often, while rummaging around for a personnel file or company directive, I'll gaze upon the pictures and be transported back to the two years that were spent club roadracing—the friendship between competitors, the pride in bike preparation, the backand-forth dices, the plastic trophies held aloft as if they were Olympic gold. I don't think about the Austin crash much. And when I do, I find myself singing the refrain from a favorite country-and-western song. The ride with you, my friend, it goes, was worth the fall.

It’s a love ballad. Entirely appropriate. 63

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

December 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

December 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1990 -

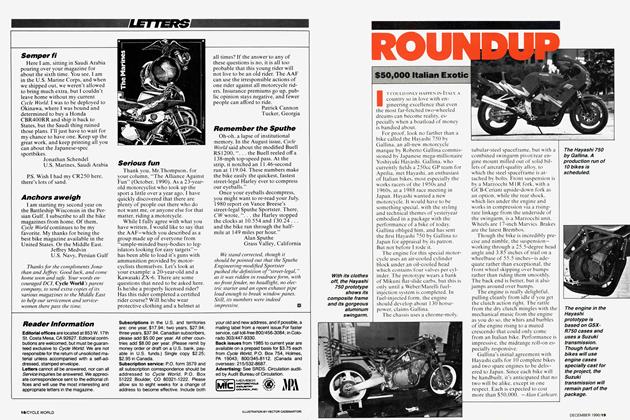

Roundup

Roundup$50,000 Italian Exotic

December 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupIndian Wars of 1991

December 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupCw 25 Years Ago December, 1965

December 1990 By Doug Toland