UP FRONTA

Memory's keeper

David Edwards

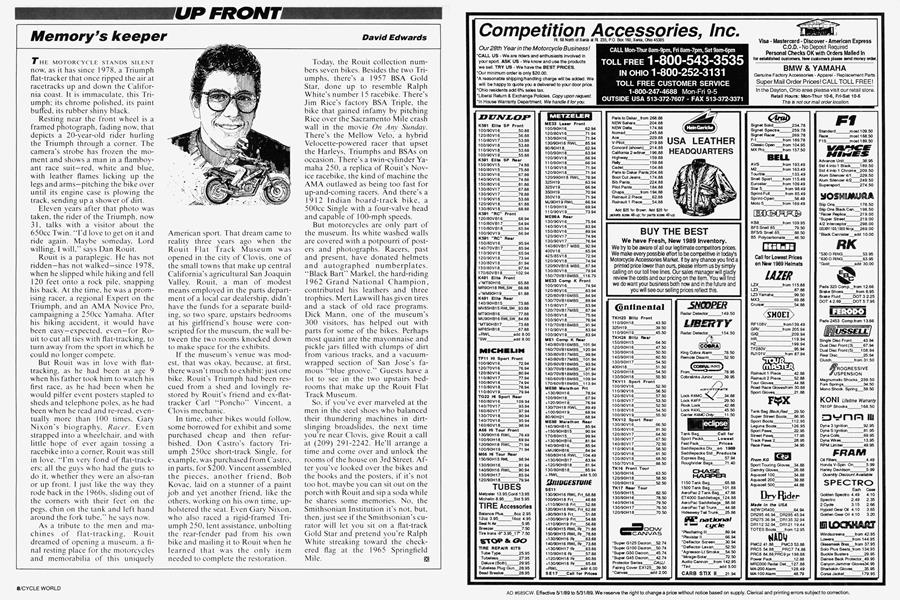

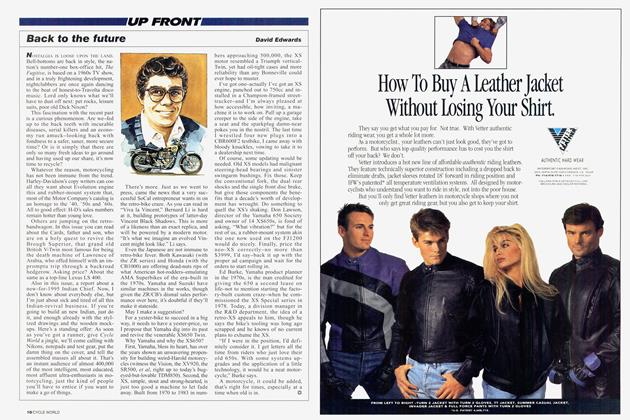

THE MOTORCYCLE STANDS SILENT now. as it has since 1978, a Triumph flat-tracker that once ripped the air at racetracks up and down the California coast. It is immaculate, this Triumph; its chrome polished, its paint buffed, its rubber shiny black.

Resting near the front wheel is a framed photograph, fading now', that depicts a 20-year-old rider hurling the Triumph through a corner. The camera’s strobe has frozen the moment and shows a man in a flamboyant race suit—red, white and blue, with leather flames licking up the legs and arms—pitching the bike over until its engine case is plowing the track, sending up a shower of dirt.

Eleven years after that photo was taken, the rider of the Triumph, now 31, talks with a visitor about the 650cc Tw'in. “I’d love to get on it and ride again. Maybe someday. Lord willing, I will." says Dan Rouit.

Rouit is a paraplegic. He has not ridden—has not walked—since 1978, when he slipped while hiking and fell 120 feet onto a rock pile, snapping his back. At the time, he was a promising racer, a regional Expert on the Triumph, and an AMA Novice Pro, campaigning a 250cc Yamaha. After his hiking accident, it would have been easy—expected, even—for Rouit to cut all ties with flat-tracking, to turn away from the sport in which he could no longer compete.

But Rouit was in love with flattracking. as he had been at age 9 when his father took him to watch his first race, as he had been when he would pilfer event posters stapled to sheds and telephone poles, as he had been when he read and re-read, eventually more than 100 times. Gary Nixon’s biography. Racer. Even strapped into a wheelchair, and with little hope of ever again tossing a racebike into a corner. Rouit was still in love. “I'm very fond of flat-trackers; all the guys who had the guts to do it, whether they were an also-ran or up front. I just like the way they rode back in the 1960s, sliding out of the corners with their feet on the pegs, chin on the tank and left hand around the fork tube," he says now'.

As a tribute to the men and machines of flat-tracking. Rouit dreamed of opening a museum, a final resting place for the motorcycles and memorabilia of this uniquely American sport. That dream came to reality three years ago when the Rouit Flat Track Museum was opened in the city of Clovis, one of the small tow ns that make up central California’s agricultural San Joaquin Valley. Rouit, a man of modest means employed in the parts department of a local car dealership, didn't have the funds for a separate building. so two spare, upstairs bedrooms at his girlfriend's house were conscripted for the museum, the wall between the two rooms knocked down to make space for the exhibits.

If the museum’s venue was modest, that was okay, because, at first, there wasn't much to exhibit: just one bike. Rouit's Triumph had been rescued from a shed and lovingly restored by Rouit's friend and ex-flattracker Carl “Poncho” Vincent, a Clovis mechanic.

In time, other bikes would follow, some borrowed for exhibit and some purchased cheap and then refurbished. Don Castro's factory Triumph 250cc short-track Single, for example, was purchased from Castro, in parts, for $200. Vincent assembled the pieces, another friend, Bob Kovac, laid on a stunner of a paint job and yet another friend, like the others, working on his own time, upholstered the seat. Even Gary Nixon, who also raced a rigid-framed Triumph 250, lent assistance, unbolting the rear-fender pad from his own bike and mailing it to Rouit when he learned that was the only item needed to complete the restoration.

Today, the Rouit collection numbers seven bikes. Besides the two Triumphs, there’s a 1957 BSA Gold Star, done up to resemble Ralph White's number 1 5 racebike. There's Jim Rice’s factory BSA Triple, the bike that gained infamy by pitching Rice over the Sacramento Mile crash wall in the movie On Any Sunday. There's the Mellow Velo, a hybrid Velocette-powered racer that upset the Harleys, Triumphs and BSAs on occasion. There's a twin-cylinder Yamaha 250, a replica of Rouit’s Novice racebike. the kind of machine the AMA outlawed as being too fast for up-and-coming racers. And there’s a 1912 Indian board-track bike, a 500cc Single with a four-valve head and capable of 100-mph speeds.

But motorcycles are only part of the museum. Its white washed walls are covered with a potpourri of posters and photographs. Racers, past and present, have donated helmets and autographed numberplates. “Black Bart” Marked, the hard-riding 1962 Grand National Champion, contributed his leathers and three trophies. Mert Lawwill has given tires and a stack of old race programs. Dick Mann, one of the museum’s 300 visitors, has helped out with parts for some of the bikes. Perhaps most quaint are the mayonnaise and pickle jars filled with clumps of dirt from various tracks, and a vacuumwrapped section of San Jose's famous “blue groove." Guests have a lot to see in the two upstairs bedrooms that make up the Rouit Flat Track Museum.

So, if you've ever marveled at the men in the steel shoes who balanced their thundering machines in dirtslinging broadslides, the next time you’re near Clovis, give Rouit a call at (209) 291-2242. He'll arrange a time and come over and unlock the rooms of the house on 3rd Street. After you've looked over the bikes and the books and the posters, if it's not too hot. maybe you can sit out on the porch with Rouit and sip a soda while he shares some memories. No, the Smithsonian Institution it’s not, but, then, just see if the Smithsonian’s curator will let you sit on a flat-track Gold Star and pretend you're Ralph White streaking toward the checkered flag at the 1965 Springfield Mile.