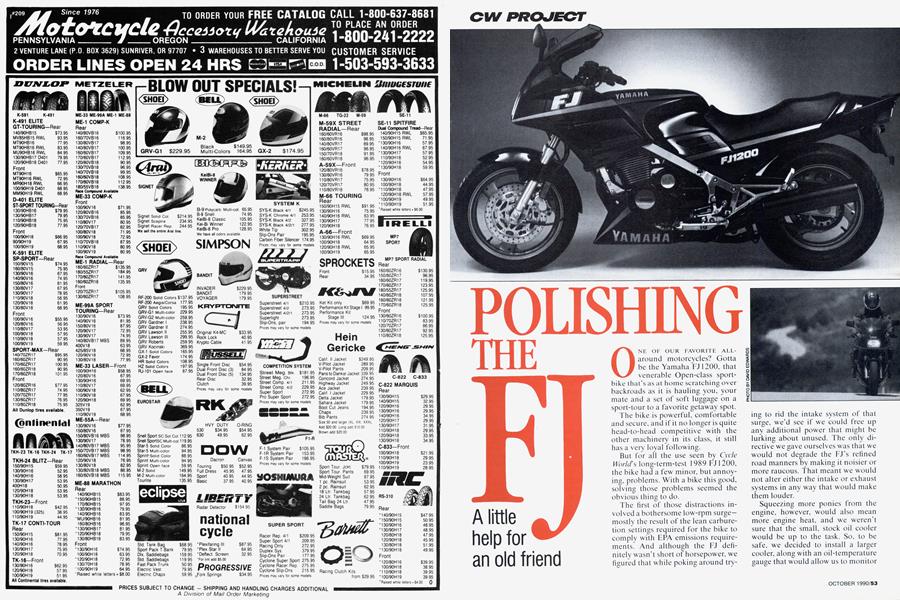

POLISHING THE FJ

CW PROJECT

A little help for an old friend

ONE OF OUR FAVORITE ALL-around motorcycles? Gotta be the Yamaha FJ1200, that venerable Open-class sport-bike that's as at home scratching over backroads as it is hauling you, your mate and a set of soft luggage on a sport-tour to a favorite getaway spot.

The bike is powerful, comfortable and secure, and if it no longer is quite head-to-head competitive with the other machinery in its class, it still has a very loyal following.

But for all the use seen by Cycle Worlds long-term-test 1989 FJ1200, the bike had a few minor, but annoying, problems. With a bike this good, solving those problems seemed the obvious thing to do.

The first of those distractions involved a bothersome low-rpm surgemostly the result of the lean carburetion settings required for the bike to comply with EPA emissions requirements. And although the FJ definitely wasn’t short of horsepower, we figured that while poking around trying to rid the intake system of that surge, we’d see if we could free up any additional power that might be lurking about unused. The only directive we gave ourselves was that we would not degrade the FJ's refined road manners by making it noisier or more raucous. That meant we would not alter either the intake or exhaust systems in any way that would make them louder.

Squeezing more ponies from the engine, however, would also mean more engine heat, and we weren’t sure that the small, stock oil cooler would be up to the task. So, to be safe, we decided to install a larger cooler, along with an oil-temperature gauge that would allow us to monitor the heat-dissipation differences between the stock oil radiator and the larger one.

As it turned out, just finding an oiltemperature gauge for the FJ was a project in itself. A check of the most likely aftermarket sources came up empty, and we finally tracked down an illuminated, one-size-fits-all gauge in the automotive catalog of J.C. Whitney, the well-known mailorder company in Chicago.

After receiving the gauge about a week after placing the order, we found that installing it was no walk in the park, either. We had to remove the entire exhaust system to gain access to the oil pan, which had to be removed, drilled and tapped to accept the gauge's sending unit. And while tapping the hole, we found that, because the walls of the pan are quite thin, there would be only three coarse threads holding the sending unit in place. We effected a quick fix by sealing the threads with Teflon tape and applying some epoxy around the junction of the sending unit and the oil pan; a more-permanent solution would be to heliarc a suitable nut or threaded collar to the oil pan to give the sending unit more purchase.

Fitting and wiring the gauge itself involved dismantling a few right-side body pieces and cutting a 2-inch-diameter hole in the inner-right fairing panel. That location put the gauge where the rider could always see it, even if he was wearing a full-coverage helmet. We glued a strip of foam to the gauge where it seats against the panel to help dampen vibration.

Once we got the oil-temperature gauge installed, we took the FJ to John Cordona at Fours N' More in Reseda, California, for installation of the larger oil cooler ($349, including mounting, fittings and steelbraided lines), and to have the lowrpm surge exorcised. Cordona also agreed to see if he could boost engine performance without making the FJ noisier, but admitted that he would be exploring new territory. “Fve never done anything like this before,” he explained, “but we’ll never see how it works unless we try.”

Cordona began by rejetting the carburetors, eventually settling on No. 0.8 air jets (up from 0.6), No. 40 pilots (up from 37.5) and No. 125 main jets (up from 1 10), with the needles shimmed 0.20 inch higher. He then degreed the camshaft lobe centers to 104 and 106 degrees, respectively, for the intake and exhaust. “That’s where FJs run best,” he said. And he swapped the original, pleated-paper air filter for an oiled-gauze K&N stock-replacement unit that permits greater airflow without increasing intake noise. Cost of the carb-and-cam fiddling came to $236, including about $20 worth of new jets.

After these modifications, no trace of the low-rpm surge remained. The càrburetion was sharp and crisp everywhere in the entire rpm range, and the FJ’s powerband seemed as wide as ever. Plus, the oil temperature during normal running ranged from 190 to 240 degrees F, about 10 degrees less than with the stock cooler.

But somewhat to our surprise, the overall performance was not improved at all. The quarter-mile and 40-to-60-mph roll-on times were virtually identical, and the 60-to-80 roll-ons were actually a tick slower (3.25 seconds, compared with 3.05 for the stocker), although the difference wasn’t great enough to feel in the seat of the pants. Obviously, coaxing more power from the FJ would have required exactly what we didn’t want: more noise.

One area that we knew for sure could be improved was the suspension. The FJ was so softly sprung that simply pushing it off its centerstand would use up most of the suspension travel. And when the FJ was ridden at a brisk pace on a winding road, both the front and rear suspension would compress too quickly and rebound too slowly, causing the bike to wallow in the faster corners.

The cure for the rear was simple: Crank up the preload adjuster to the maximum setting. But the front fork required stiffer springs, which we obtained from Progressive Suspension. Once the FJ was set up this way, the wallowing vanished; and although the suspension was then firm enough to provide good chassis control and stability, it still was compliant enough for a smooth ride.

We decided to finish off the package with tires that would work well with the improved suspension. We chose Avon radiais (a 120/70VR17 ST22 up front and a 160/80VR17 ST23 in the rear) because they are touted as general-use/sport-touring tires rather than pure-sport/racetrack specials. That seemed a perfect complement to the FJ1200’s intended all-around mission.

And. indeed, the Avons did deliver a significant performance improvement over the stock Dunlop K330s. They gave better cornering traction and feedback when pushed at a sporttouring pace on twisty roads, provided a noticeably smoother ride, and made rain grooves and most pavement transitions seem to disappear altogether.

So, in the end, our project was a qualified success. Admittedly, we were unable to make the FJ 1200 any faster, but only because of our selfimposed noise constraints—and because Yamaha obviously did a commendable job of engineering the bike’s EPA-legal intake and exhaust systems in the first place. But we did succeed in making the FJ run more smoothly, handle more precisely, ride more comfortably and deliver more engine-status information to the rider.

That’s no small achievement on a bike like the FJ1200. It’s a terrific ride just the way it comes from Yamaha. And with just a little fiddling, it can be made even better. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1990 -

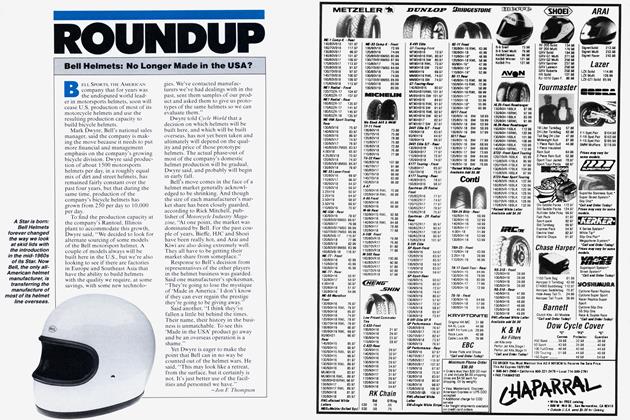

Roundup

RoundupBell Helmets: No Longer Made In the Usa?

October 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Update: News From Cagiva, Aprilia And Ferrari

October 1990 By Alan Cathcart