NORTON'S BACK!

Joining the rotary club

ALAN CATHCART

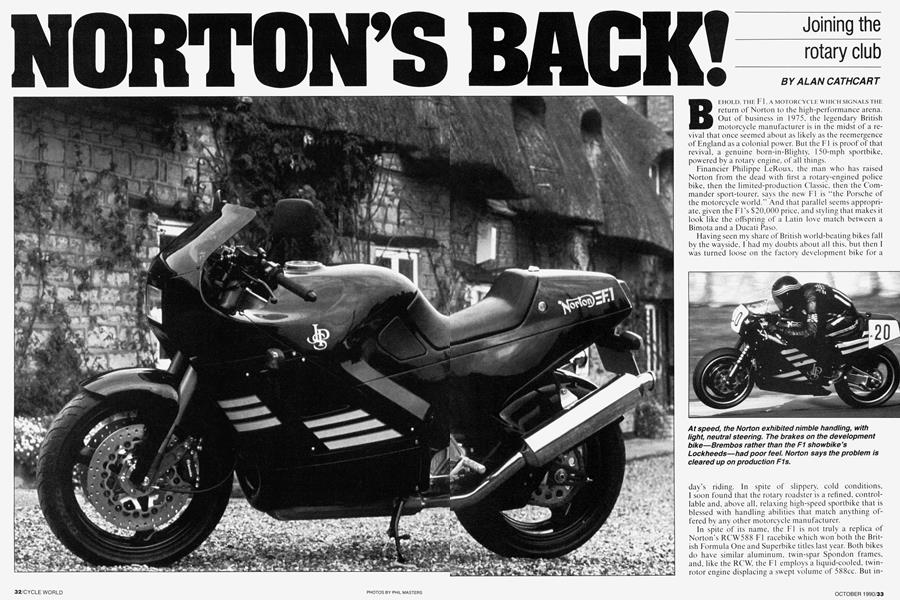

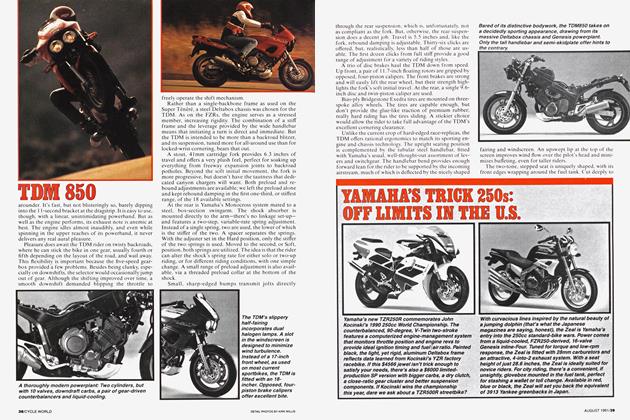

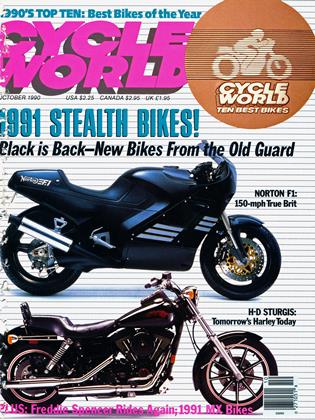

BEHOLD, THE F1, A MOTORCYCLE WHICH SIGNALS THE return of Norton to the high-performance arena. Out of business in 1975, the legendary British motorcycle manufacturer is in the midst of a revival that once seemed about as likely as the reemergence of England as a colonial power. But the F1 is proof of that revival, a genuine born-in-Blighty, 150-mph sportbike, powered by a rotary engine, of all things.

Financier Philippe LeRoux, the man who has raised Norton from the dead with first a rotary-engined police bike, then the limited-production Classic, then the Commander sport-tourer, says the new FI is “the Porsche of the motorcycle world.” And that parallel seems appropriate, given the F1's $20,000 price, and styling that makes it look like the offspring of a Latin love match between a Bimota and a Ducati Paso.

Having seen my share of British world-beating bikes fall by the wayside, I had my doubts about all this, but then I was turned loose on the factory development bike for a day’s riding. In spite of slippery, cold conditions, I soon found that the rotary roadster is a refined, controllable and, above all, relaxing high-speed sportbike that is blessed with handling abilities that match anything offered by any other motorcycle manufacturer.

In spite of its name, the FI is not truly a replica of Norton’s RCW588 FI racebike which won both the British Formula One and Superbike titles last year. Both bikes do have similar aluminum, twin-spar Spondon frames, and, like the RCW, the FI employs a liquid-cooled, twinrotor engine displacing a swept volume of 588cc. But instead of the racer’s antique, Triumph-based transmission, the FI is fitted with a five-speed Yamaha FZR1000 gear cluster. This is carried in a Norton casing and is mated to a hydraulically operated clutch.

The fitting of the Yamaha gearbox necessitated a complete revamp of the engine layout. With only two shafts rather than three as on the old gearbox, the Yamaha transmission required that the engine run “backwards.” This was accomplished by simply turning the Norton’s rotor housing—akin to a conventional engine’s cylinders and block—around 180 degrees. The revisions made for a more-compact powerplant, and in turn enabled Spondon and Norton to produce a bike that is more 500 GP racer than superbike in terms of overall size. However, it also meant there was no room for the car-type SU carburetors used on the police and touring versions, leading to the adoption of a pair of downdraft 34mm Mikunis as fitted to the FZ750 Yamaha. That revision permits shorter inlet tracts, which, coupled with revised port timing and much larger inlet ports, enable the FI engine to deliver more power at the top-end than the sport-touring Commander engine: 94 horsepower at 9500 rpm, against the Commander’s 85 horsepower at 9000 rpm.

This may sound humble by modern hyperbike standards, but it is sufficient to propel the FI roadster to an indicated 155 miles per hour by the time the rev limiter cuts in at 10,500 rpm, though in terms of outright acceleration, conventionally motored 750 and lOOOcc sportbikes will leave it well behind. But, as Norton has shown with the RCW racer, which now produces about 140 horsepower, the rotary engine is capable of being tuned to a considerable extent without losing flexibility or torque.

Except for being flip-flopped, the FI’s rotor housing is the same as the Commander's, and contains cast-iron rotors which are sent to Mazda in Japan to have their allimportant tips machined before being returned to Norton for final assembly. Lubrication is handled by a two-strokestyle injection system, with oil supplied from a 2.5-quart tank located below the seat. Oil is injected directly into the main bearings, at the rate of about 1 quart per 900 miles, via a metering unit on the right side of the rotor housing. Both the gearbox and primary drive have their own separate oil supplies.

Thumb the starter button, and the FI throbs into life, settling at a potent, lumpy, 1 500-rpm idle. When you twist the throttle a little, the exhaust note changes to that of a heavily muffled marine outboard, but in anything approaching normal working conditions, the exhaust note remains a unique song.

Though the FI will pull smoothly from very low revs, its sporting state of tune means that real power is only available from 5000 rpm onwards. Above that, the engine’s rendezvous with its rev-limiter is surprisingly easy to keep, for the rotary engine is so uncannily smooth the rider has no real indication he’s about to intercept redline. Of course, since it has neither valves to tangle nor rods to break, the F1 engine has a theoretically infinite capacity to rev. The reality, however, is that excessive rpm tends to dramatically shorten rotor-tip life.

The rotary’s lack of vibration, coupled with its easy power delivery, wide torque band and impressive, if not exactly mind-boggling, straight-line performance, makes the FI an unusually mellow ride. You don’t feel obliged to race everywhere at ten-tenths: The Norton will tailor its behavior to your mood and the prevailing conditions, rather than create the subconscious expectation that it needs to be ridden flat-out all day long.

The engine’s only disconcerting traits are a hesitation when the throttle is suddenly cracked open; a tendency to hunt and snatch at small throttle openings; and a mild graunching noise on the overrun, caused by backlash in the engine’s stationary gears, on which the rotors turn, when the engine is not under load. You only notice the noise at lower rpm, but it is there and is at odds with the otherwise sophisticated feel of the bike.

Part of that sophistication comes from the bike’s White Power suspension, which combines with the rigid frame to offer a very high level of handling. Steering is light and precise, and the longish, 57-inch wheelbase imparts security and stability in fast corners. The Fl uses a White Power upside-down fork and a revised version of the same shock the racer uses, coupled to a street-rate linkage system. Though set on maximum softness for my ride, the 4.3-inch-travel fork took even the bumpiest backroads in stride. The rear end was just as good, with smooth, progressive response and 5.6 inches of wheel travel.

One notable aspect of riding the FI on craggy country lanes was how taut and “together” it felt. Despite it being a prototype, there were no creaks or squeaks from the tight-fitting bodywork, only that distinctive, subdued rotary burble from the twin exhaust pipes.

About that bodywork: Drawn for Norton by the British designer firm Seymour/Powell, it has won several important awards, including Best Overall Design, in a prestigious British competition sponsored by Design Week magazine.

Norton, which as of mid-June had delivered its first 17 FIs, one of which was immediately stolen from its south London owner and quickly recovered, is in the process of homologating a 49-state version of the Fl for sale in the U.S. later this year under rules set up for low-volume manufacturers. Satisfying California’s more stringent emissions and noise requirements may take longer. But, said Norton spokesman David O’Neill, “We regard this as a key market for the bike, so we’ll be working to get the FI on sale throughout the U.S. by the end of the year.” U.S. marketing of the bike is tentatively scheduled to commence with a fall, 1990 advertising campaign.

So, what we have here is a Made in England superbike for the 1990s, a motorcycle that proves that miracles can happen, even in the Britbike business. The FI, risen from the ashes of the Dominator, the Manx and the Commando, has put life back in the fabled Norton name. Perhaps this bike’s nickname ought to be Phoenix. ®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1990 -

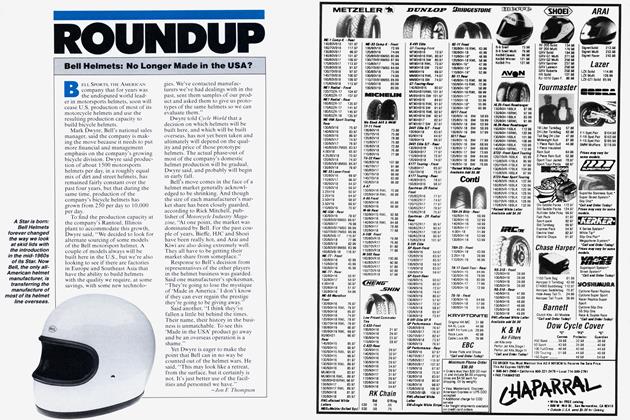

Roundup

RoundupBell Helmets: No Longer Made In the Usa?

October 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Update: News From Cagiva, Aprilia And Ferrari

October 1990 By Alan Cathcart