AT LARGE

The Alliance Against Fun

Steven L. Thompson

SO WE'RE STANDING THERE, LATE Braker Williams and I, talking to the young sales manager of Rick’s Cycle Center in Bound Brook, New Jersey, and suddenly Williams gives us the answer to the question everybody in the motorcycle biz is asking: Why aren’t the kids buying motorcycles?

It happened when we were all agreeing that the problem with the idea of “standard” motorcycles as the panacea for lousy sales is that resurrecting UJMs seems to appeal mostly to fortysomethings, insofar as it really appeals to anyone. For the youngersomethings (and, for a whole lot of othersomethings, too), the old, proven formula for mixing hormones with gasoline still sells. Call it speed with style. Call it FZRs, GSXRs, ZXs, and VFRs.

Call it mostly unattainable for middle-class American youth, Williams said, thanks to the Alliance Against Fun. In his view, the root cause of motorcycling’s malaise.

If some other guy had told me this, I’d have headed for the exit. But James E. “Late Braker” Williams has earned the right to opine on the subject of speed and fun and the bureaucratic forces of darkness.

I met him at Car and Driver magazine, where he was doing a second tour and I my only tour. Following our joint departure from C/D when its czar moved it to Michigan from Manhattan, we collaborated on various magazine design projects, and he went off to learn, as he put it, “everything else a guy could learn” about the car biz.

Since he already knew how to design and build cars, what that meant was that he worked as: PR guy for Volvo, advertising creative guy on the VW, Audi, Porsche, Toyota, Jaguar and Saab accounts, and forwardplanning guy for Chrysler’s ad agency. As well as creative director of an agency that dealt with one of the biggest car retail dealer networks in the country. Along the way, he built and raced such diverse hardware as MGTFs and RZ350s. And also studied, as a professional, the social and governmental forces affecting the automotive world. In sum, this is a guy you listen to when the subject is internal-combustion enthusiasm, or anything relating thereto.

So I did. And he described how the Alliance Against Fun works to keep kids out of motorcycling . . . how, in fact, it tries to keep everyone out of motorcycling. Basically, through insurance premiums.

When the sales manager at my local bike shop tries to put a 20-yearold onto a Kawasaki ZX-6, he faces not only the price hurdle of the machine, but a tremendous barrier in the insurance. A barrier that has risen silently, swiftly and inexorably to block more and more people from riding. People like that 20-year-old, who, based on the McGraw Insurance Ratings Guide, would have to cough up $3313 per year to ride a 600cc Kawasaki in California.

That’s not a typo. Three thousand plus. Per year. The cost of a good used bike, every 12 months. Any reasonable, not-rich guy would run up against numbers like that and kiss off motorcycles. Probably forever.

Which is, according to Williams, the whole point of the AAF. His theory is that what’s going on here is not simply the insurance guys penalizing the ZX-kid for his statistical propensity for crashing, as well as the eyepopping expense of replacing all that plastic if he does.

What’s going on, he thinks, is that the safety-Nazis are trying to kill off motorcycling altogether.

It’s not, he argues, simply a matter of money. What he thinks is happening is that our society has inadvertently allowed social “minders” to flourish almost beyond control, dictating anonymously for all of us what is correct behavior and what is not. And somehow, motorized fun—on motorcycles, jet skis, sports cars, even ultralights—has become a target for the minders.

What Williams sees behind our astronomical insurance costs is a kind of counter-revolution against the ideals that established America. Fuelled by people with genuine social and ecological concerns, perhaps, but driven by righteous zealots.

Extended beyond the confines of the Rick’s Cycle Center issues, this line of thought might lead to an extreme form of civil libertarianism. Late Braker does not go that far. He stops at postulating the existence of the Alliance Against Fun.

Who are the members of the alliance? Williams can elucidate them clearly, from simple-minded busybodies to legislators looking for easy targets. But behind most of them stand the self-serving insurance-industry organizations, which operate smoothly in the corridors of power to promulgate their views. Organizations which wield their clout without fear of accountability to anyone. And which, having failed to legislate motorcycles out of existence (remember the Danforth Debacle?), have shifted their strategy to simple economic warfare.

Is he right? I don’t know how you’d prove it. But worse, if it’s true, I don’t know how you'd fix it. Unless you took another Williams thesis and made it work.

That’s the one in which the manufacturers underwrite their customers’ insurance themselves. Doing so, he argues, is about the only way that the agenda of the alliance can be slowed. And without slowing the agenda, motorcycling, Williams thinks, will ultimately become uninsurable and unaffordable for most people.

It’s a bleak view. But no bleaker than showrooms full of hardware that young people want but cannot afford to insure. And certainly no bleaker than what might follow that: no showrooms at all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

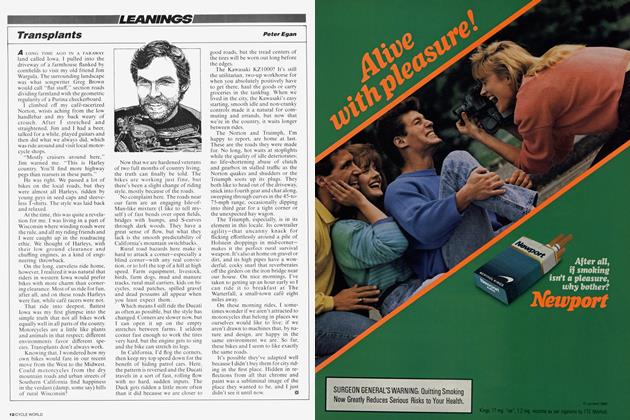

ColumnsLeanings

October 1990 By Peter Egan -

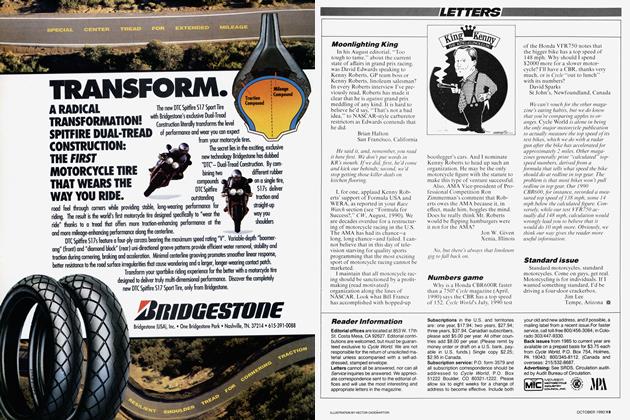

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1990 -

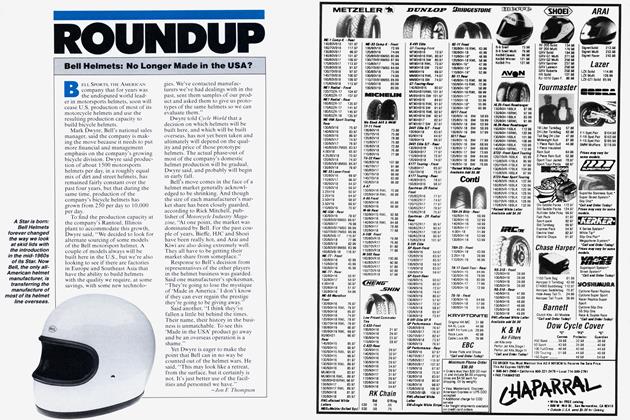

Roundup

RoundupBell Helmets: No Longer Made In the Usa?

October 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Update: News From Cagiva, Aprilia And Ferrari

October 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

October 1990 By Ron Griewe