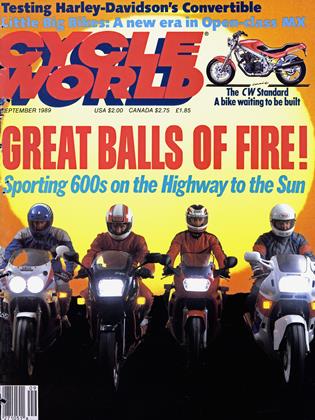

THE CYCLE WORLD CONVERTIBLE

Modular motorcycling for the masses

WE THINK HARLEY-DAVIDSON'S CONVERTible is one of the better ideas to come along in a while. And like all good ideas, it has spawned others, among them, this one: One of Japan’s Big Four ought to build its own version of the Convertible, one based upon the once-endangered, and now re-emergent, standard chassis, but with a sporting flavor.

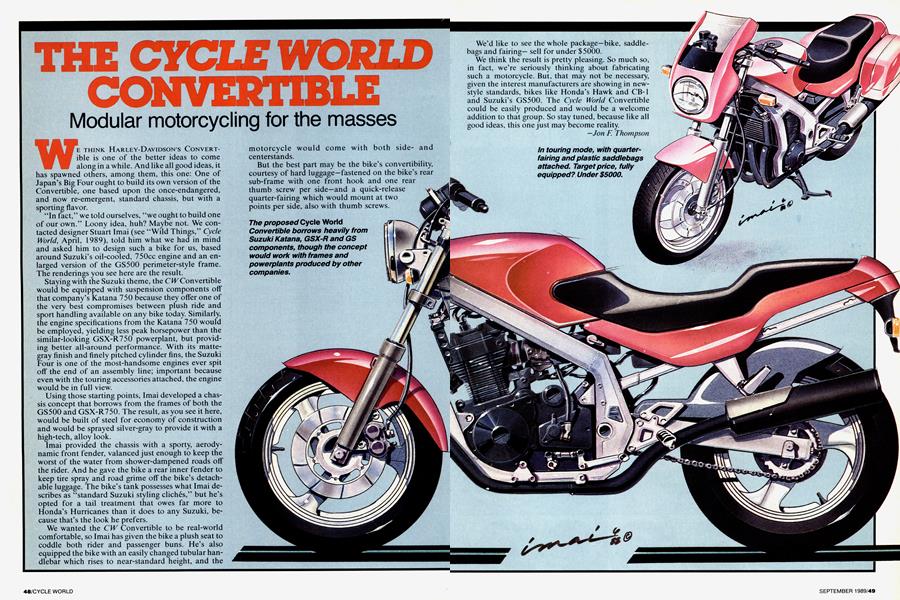

“In fact,” we told ourselves, “we ought to build one of our own.” Loony idea, huh? Maybe not. We contacted designer Stuart Imai (see “Wild Things,” Cycle World, April, 1989), told him what we had in mind and asked him to design such a bike for us, based around Suzuki’s oil-cooled, 750cc engine and an enlarged version of the GS500 perimeter-style frame. The renderings you see here are the result.

Staying with the Suzuki theme, the OF Convertible would be equipped with suspension components off that company’s Katana 750 because they offer one of the very best compromises between plush ride and sport handling available on any bike today. Similarly, the engine specifications from the Katana 750 would be employed, yielding less peak horsepower than the similar-looking GSX-R750 powerplant, but providing better all-around performance. With its mattegray finish and finely pitched cylinder fins, the Suzuki Four is one of the most-handsome engines ever spit off the end of an assembly line; important because even with the touring accessories attached, the engine would be in full view.

Using those starting points, Imai developed a chassis concept that borrows from the frames of both the GS500 and GSX-R750. The result, as you see it here, would be built of steel for economy of construction and would be sprayed silver-gray to provide it with a high-tech, alloy look.

Imai provided the chassis with a sporty, aerodynamic front fender, valanced just enough to keep the worst of the water from shower-dampened roads off the rider. And he gave the bike a rear inner fender to keep tire spray and road grime off the bike’s detachable luggage. The bike’s tank possesses what Imai describes as “standard Suzuki styling clichés,” but he’s opted for a tail treatment that owes far more to Honda’s Hurricanes than it does to any Suzuki, because that’s the look he prefers.

We wanted the CW Convertible to be real-world comfortable, so Imai has given the bike a plush seat to coddle both rider and passenger buns. He’s also equipped the bike with an easily changed tubular handlebar which rises to near-standard height, and the

motorcycle would come with both sideand centerstands.

But the best part may be the bike’s convertibility, courtesy of hard luggage—fastened on the bike’s rear sub-frame with one front hook and one rear thumb screw per side—and a quick-release quarter-fairing which would mount at two points per side, also with thumb screws.

We’d like to see the whole package—bike, saddlebags and fairing— sell for under $5000.

We think the result is pretty pleasing. So much so in fact, we’re seriously thinking about fabricating such a motorcycle. But, that may not be necessary, given the interest manufacturers are showing in newstyle standards, bikes like Honda’s Hawk and CB-1 and Suzuki’s GS500. The Cycle World Convertible could be easily produced and would be a welcome addition to that group. So stay tuned, because like all good ideas, this one just may become reality.

Jon F. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

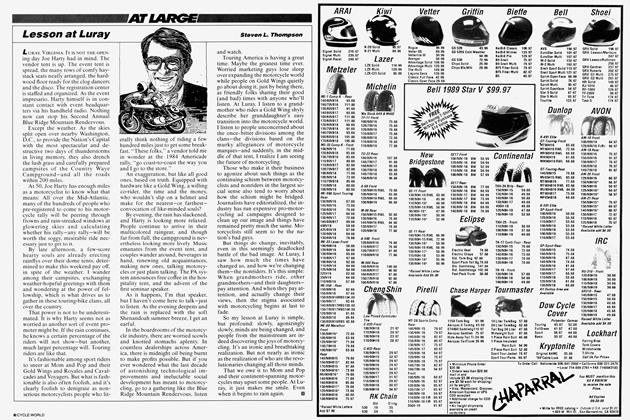

ColumnsAt Large

September 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

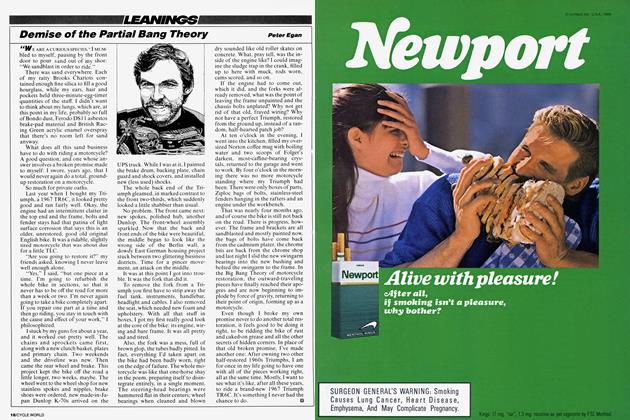

ColumnsLeanings

September 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

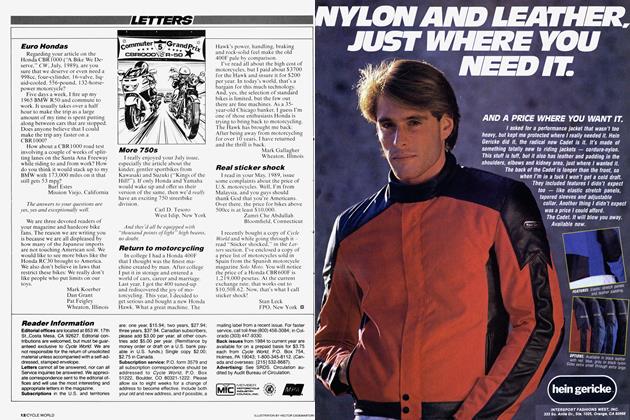

LettersLetters

September 1989 -

Roundup

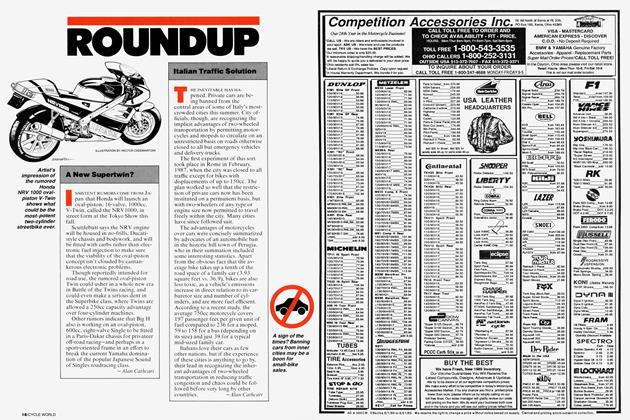

RoundupA New Supertwin?

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Traffic Solution

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart