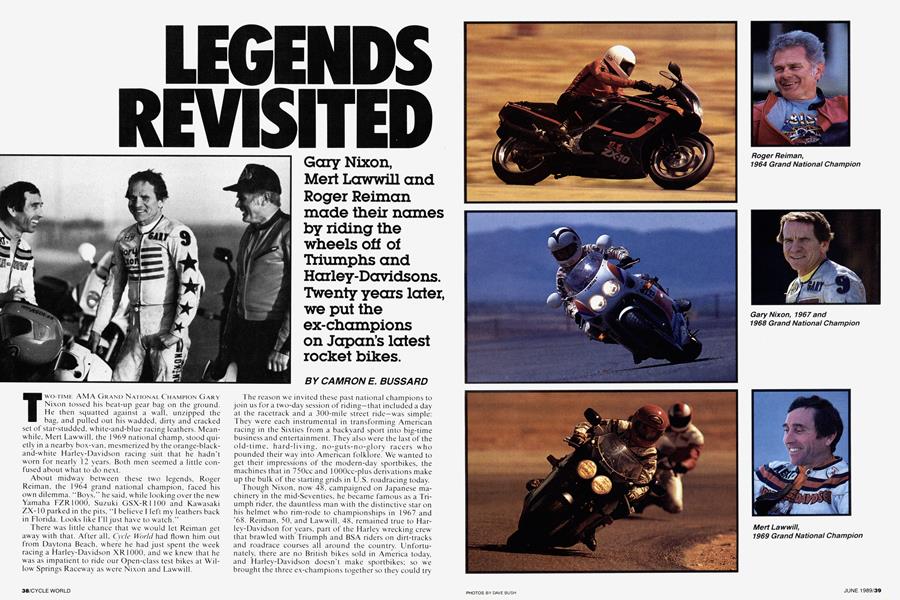

LEGENDS REVISTED

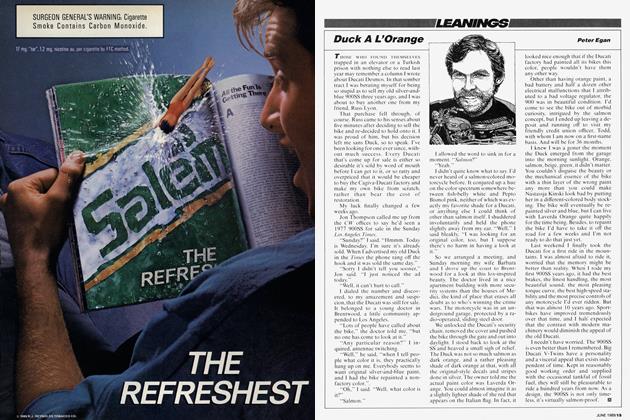

Gary Nixon, Mert Lawwill and Roger Reiman made their names by riding the wheels off of Triumphs and Harley-Davidsons. Twenty years later, we put the ex-champions on Japan's latest rocket bikes.

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

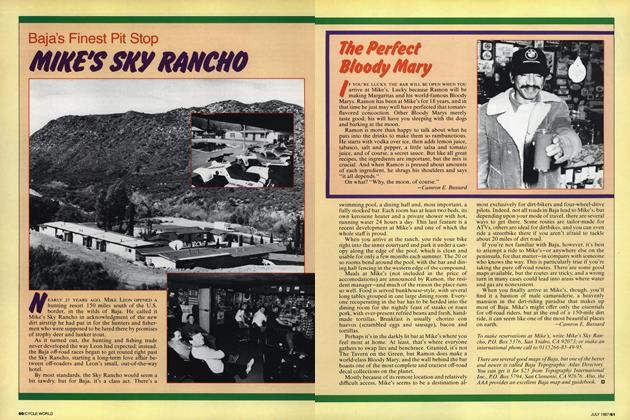

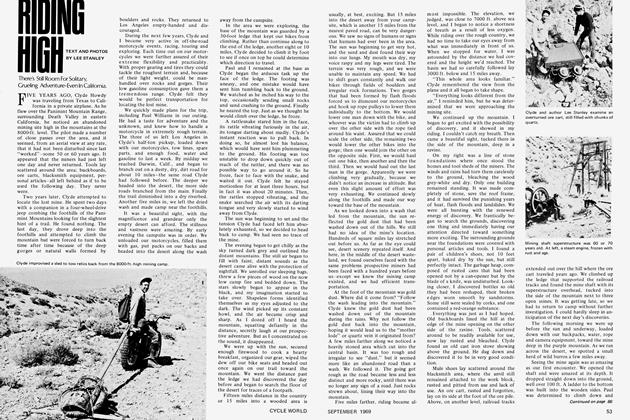

TWO-TIME AMA GRAND NATIONAL CHAMPION GARY Nixon tossed his beat-up gear bag on the ground. He then squatted against a wall, unzipped the bag, and pulled out his wadded, dirty and cracked set of star-studded, white-and-blue racing leathers. Meanwhile, Mert Lawwill, the 1969 national champ, stood quietly in a nearby box-van, mesmerized by the orange-blackand-white Harley-Davidson racing suit that he hadn't worn for nearly 12 years. Both men seemed a little confused about what to do next.

About midway between these two legends, Roger Reiman, the 1964 grand national champion, faced his own dilemma. “Boys," he said, while looking over the new Yamaha FZR1000, Suzuki GSX-R1100 and Kawasaki ZX-10 parked in the pits, “I believe 1 left my leathers back in Florida. Looks like I'll just have to watch."

There was little chance that we would let Reiman get away with that. After all, Cycle World had flown him out from Daytona Beach, where he had just spent the week racing a Harley-Davidson XR1000, and we knew that he was as impatient to ride our Open-class test bikes at Willow Springs Raceway as were Nixon and Lawwill.

The reason we invited these past national champions to join us for a two-day session of riding—that included a day at the racetrack and a 300-mile street ride—was simple: They were each instrumental in transforming American racing in the Sixties from a backyard sport into big-time business and entertainment. They also were the last of the old-time, hard-living, no-guts-no-glory racers who pounded their way into American folklore. We wanted to get their impressions of the modern-day sportbikes, the machines that in 750cc and 1 OOOcc-plus derivations make up the bulk of the starting grids in U.S. roadracing today.

Though Nixon, now 48, campaigned on Japanese machinery in the mid-Seventies, he became famous as a Triumph rider, the dauntless man with the distinctive star on his helmet who rim-rode to championships in 1967 and '68. Reiman, 50, and Lawwill. 48, remained true to Harley-Davidson for years, part of the Harley wrecking crew that brawled with Triumph and BSA riders on dirt-tracks and roadrace courses all around the country. Unfortunately, there are no British bikes sold in America today, and Harley-Davidson doesn't make sportbikes; so we brought the three ex-champions together so they could try out the ultimate in performance machinery from Japan, the FZR 1000, GSX-R 1 100 and ZX-10.

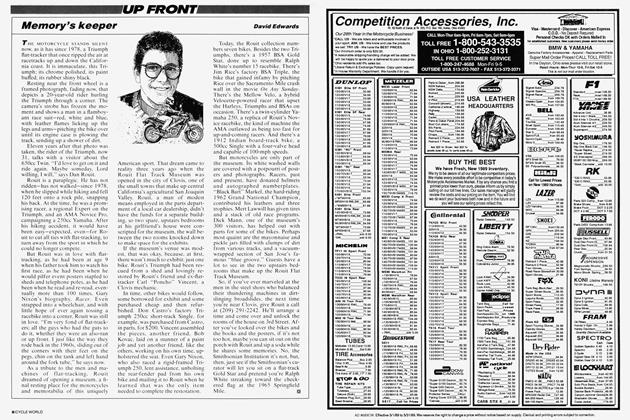

Nixon was perhaps the most notoriously flamboyant of the trio in his heyday, but he has overcome his legendary problems with alcohol and now runs a hobby shop for remote-control model cars. He stopped racing in 1976, although he does occasionally journey from his Maryland home to Baja. Mexico, for the run-w hat-ya-brung La Carrera street race. “I rode the race on a 250 Ninja,” he said, “and was in a photo finish with (1972 champion) Mark Brelsford after we had drafted each other for a hundred miles, but the camera was broken, so 1 don't know for sure who won.”

Lawwill, charismatic and outgoing, has been a fixture in American racing—as first a rider and then a tuner—since 1958. “But for the first time in 30 years,” the Northern California resident said. “I won't be on the circuit.” That's because last year, frustrated with the AMA and HarleyDavidson, he retired. Lawwill had stopped riding in 1977. but stayed involved as a race-team manager while also running a small company that produced chassis and engine parts for Harley dirt-track racers. When he retired from racing altogether last year, he also closed down his business.

Reiman, however, has never really retired from competition. He owns and operates a Harley-Davidson dealership in Kewanee, Illinois, that was originally opened by his father. But each year. Reiman, a soft-spoken and contemplative man. heads for the AMA season opener in Daytona (he has won the 200 three times in his career: 1961, '64 and '65) to compete in several of the support races that precede the big 200-miler on Sunday. The rest of the year finds him at the shop taking care of business.

Once we brought these three together at the track, we didn't have to wait long to see what they thought of the new machinery. Nixon quickly strapped on his helmet and took off for an exploratory lap or two around the 2.5-mile course on a Yamaha FZR400 we had along. A few minutes later, he rolled into the pits, the 400's tires feathered to their edges. “If you can convince me the chains won’t break, the tires won't go flat and the engines won't seize.” he said, motioning towards the big bikes, “I'll go for it.”

Nixon had no sooner come to a stop than Lawwill was on the 400. “just to see if I remember how to do it.” A couple of laps later, he pulled in and slipped off his helmet. With a broad grin that would seldom disappear for the next two days, he admitted. “I feel a little old and rusty,” but added, “I had forgotten how' much fun this is.” That's entirely understandable, as the last time any of the three had been to Willow Springs was way back in 1967. And none of them had ever ridden a modern Japanese sportbike.

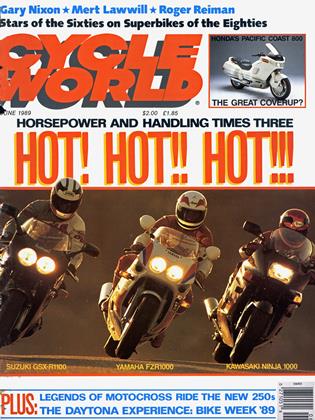

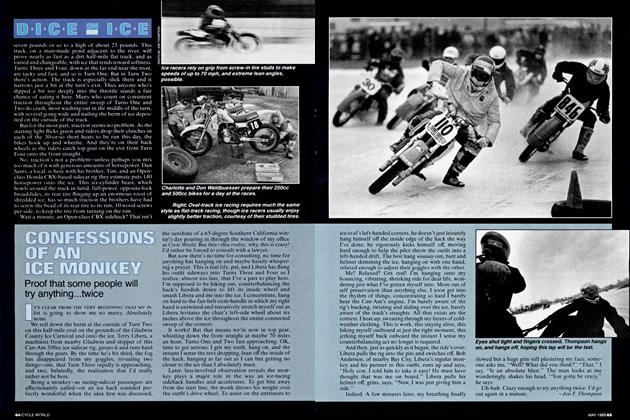

For their first track outing on the 1000s, Nixon grabbed the I ZR, Laww ill the GSX-R, and Reiman hopped on the ZX-10. Racers being racers, in a matter of minutes Law will and Nixon were locked in a dice for the lead, as if 20 years had suddenly disappeared and the two were in a down-to-the-wire run for the Number-One plate. Nixon would cue off Lawwill as both braked a little early for the corners, only to twist the throttle wide-open and rocket dow n the straights. In spite of their years away, both men rode with remarkable smoothness, carving graceful lines around the track, toes barely skimming the asphalt.

Reiman, fresh from racing at this year's Daytona, was faster and smoother yet. All three men are from an era before hanging-off was the accepted riding style, so they remained tucked-in through the turns, using their toes, rather than their knees, as feelers. “I tried hanging-off out there,” said Nixon, “but when I looked down, my knee was still two feet above the ground.”

During the lunch break, Reiman recalled the first season the three had competed against one another. “It was 1964, the year I won the championship,” he said, “and I spent the season trying to keep out of Nixon’s way,” obviously remembering some close on-track encounters. “Ah. Roger.” replied Nixon. “I never really tried to knock you down ... I was just out of control.” Law^will chuckled and remembered that in those days, when it came to roadracing, “those guys were head and shoulders above me. Dirt-track was where I was comfortable.”

While Law w ill would go on to rack up 1 5 dirt-track w ins in his career and gain a measure of immortality as one of the stars of the 1971 Bruce Brow n motorcycle documentary On Any Sunday. Reiman and Nixon would have classic roadrace battles throughout their careers, including one race at Loudon, the famous treeand lake-lined circuit in New Hampshire.

During practice for that 1964 race. Reiman would tuck in behind Nixon, hoping to learn the Triumph rider's cornering lines. “All week," laughed Nixon. “1 would back off before the turn by the lake, and Roger w ould back off, too. But during the race, 1 went through there flat out. and he tried to go with me. He went over the bars and into the water."

“I damn near drowned," recalled Reiman.

A quarter of a century after the incident, Nixon turned to Reiman and in mock apology said, “Gee, Roger, I'm sure sorry about that."

Reiman merely responded, “Paybacks are a bitch." He was referring to the flrst time that the less-experienced Nixon had faced Reiman on a roadrace course back in 1960 at Daytona. “Hell," said Nixon, “by the fourth lap. Reiman had lapped me. I think he must have passed me four times that day."

Almost 30 years later at WillowSprings, the memories of those early roadraces were put aside as Reiman, Nixon and Lawwill piled up lap after lap on 1989's fastest, besthandling sportbikes. All three men were astounded at how good the production machines are. “The bikes we roadraced w-obbled and danced all over the place," said Lawwill. “But these bikes are so stable, I can't find any bumps out there on the track." Reiman, whose current Harley racer is capable of more than 150 miles an hour, said, “My XR feels as strong as the Yamaha, but it’s been tweaked as much as it can and the Yamaha is stock, right from the showroom."

When it came time to decide which bike was the king of the track, Reiman summed up the ex-champs' consensus opinion, putting it in racer's terms: “If you set these bikes in a row. and told us that we had to chose one to race for a $ 1000 prize, you would have to get three FZR 1000s."

For the street-riding portion of our outing with the three Number Ones, we laid out a loop through the mountains and canyons of Southern California. Only Reiman had much street-riding experience; the last time that Lawwill had done any “street" riding at all was a year ago when he and Steve Morehead raced two XR750 dirt-track bikes up and down the county roads near Morehead's house; and other than at La Carrera, Nixon had not ridden a streetbike for more years than he could remember.

The flrst leg of our journey was up Ortega Highway, a famous stretch of fast, curvy Southern California road that leads to the Lookout Roadhouse cafe overlooking Lake Elsinore. Cycle Worlds staff riders know the road well, but that didn't mean that we had to poke along w hile Reiman, Nixon and Lawwill, unfamiliar with the highway's tw ists and turns, dawdled along at the rear. Lawwill, in particular, was having fun, and kept sticking a wheel under the leader just to showhe was there. Once at the cafe, the three liter-class sportbikes drew the attention of the younger riders gathered at the popular hangout, but the older guys there couldn’t believe that it was Mert Lawwill, Gary Nixon and Roger Reiman who had ridden the bikes in. Some of them would sidle up to our group, respectfully listen in for a minute, then wander off to tell their friends.

Before the day was through, we had covered more than 300 miles on some of the best motorcycling roads in the world at a pace that could best be described as on the outlying side of brisk. All three men had clearly enjoyed themselves, with Lawwill especially enchanted. Throughout the day, whenever we were faced with a choice of one road over another, his stock answer was, “Let’s do both.” By the end of the ride, however, sportbike ergonomics being what they are-and 50-year-old bones being what they are—the three champs were all ready to get off the motorcycles. Nixon, his caustic sense of humor at full strength, claimed he had never been tucked in for so long in his whole life.

On the street, as on the racetrack, each of the men agreed on the preferred machine: the Yamaha FZR1000. “I can’t believe that something that hits so hard down low still pulls so strong up on top,” said Lawwill. Nixon agreed and added, “This is the quickest thing 1 have ever ridden. It feels just like a good. Erv Kanemoto racebike,” referring to his long-time friend and tuner, the man who is now spinning the wrenches for Eddie Lawson’s 1989 grand prix effort.

When the ride was over and we were firmly ensconced in a hotel lounge engaged in some ardent bench racing, it was clear that these guys had a newfound respect for streetbikes. Nixon, between taking potshots at the former Elarley team members, clearly was amazed by the machines' competence, saying that there was just no comparison between these three fully street-legal sportbikes and the evil-handling, streetbike-based racers that he piloted in the 1970s, during the infancy of Superbike racing in America. Lawwill concurred and said, “I used to think that streetbikes weren't the real thing, but I never realized how much fun they could be. I would really love to have one, although I better find a regular means of employment first.”

But it was Reiman, the most reflective of the three, who w'as best able to sum up the modern sportbike experience. Even though he has a yearly outlet for his need for speed with his racing at Daytona, he obviously relished the day’s ride. “I could ride for 3000 miles back in Illinois, and not go around half as many turns as we did today,” he said. Then, after a pause, he continued. “And if I could ride bikes like these on roads like this. 1 probably wouldn't race at all. Ed just go out a couple of times a week for a long ride instead.” é