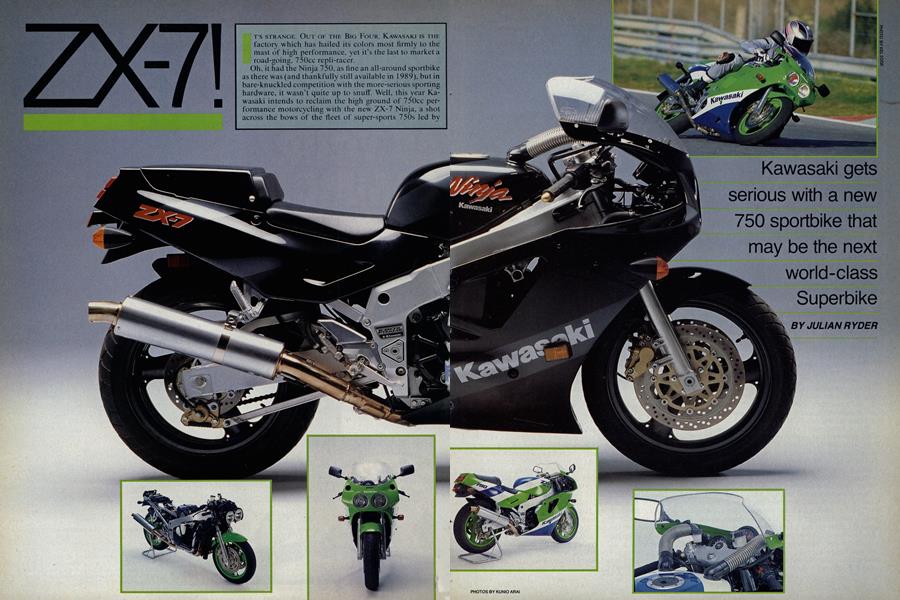

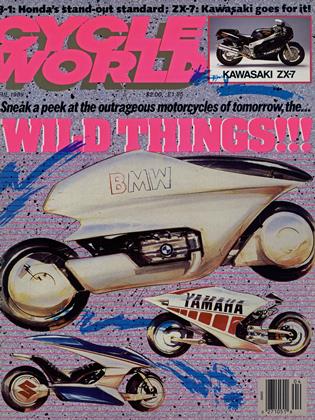

ZX-7!

IT'S STRANGE. Out OF THE BIG FOUR. KAWASAKI IS THE factory which has hailed its colors most firmly to the mast of high performance. yet it's the last to market a road-going. 750cc repli-racer.

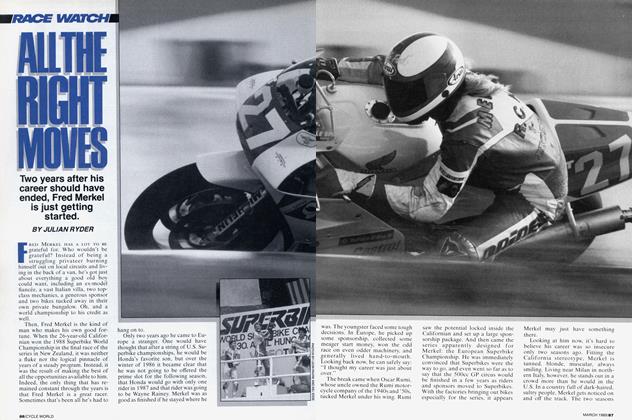

Oh. it had the Ninja 750. as fine an all-around sportbike as there was (and thankfully still available in 1989), hut in bare-knuckled competition with the more-serious sporting hardware, it wasn't quite up to snuff. Well, this year Ka wasaki intends to reclaim the high ground of 750cc per formance motorcycling with the new ZX-7 Ninja, a shot across the bows of the fleet of super-sports 750s led by Honda’s RC30, the bike that took Fred Merkel to the inaugural World Superbike Championship.

Kawasaki gets serious with a new 750 sportbike that may be the next world-class Superbike

JULIAN RYDER

Truth be told, the Japanese giants were almost humbled in that series by the Italian Bimota factory’s Yamahapowered racers. Merkel’s RC30 was down on power most of the season and the American rider owes his crown more to determination and good luck than to superior machinery (see “All the Right Moves,” CW, March, 1989). Yamaha’s own FZR750 turned out to be a worse bet in that championship than the old steel-framed FZ, and Suzuki made some fundamental chassis errors with the GSXR750J. Kawasaki’s steel-framed Ninja 750 was obviously at a disadvantage, although it did manage to sneak a win courtesy of rider Adrien Morillas.

But in Japanese FI and world endurance racing things were different. Prototype Kawasaki racebikes, called ZXR7s, with heavily modified Ninja 750 motors housed in aluminium frames, finished second in their debut at the 24 Hours of Le Mans and third at the Suzuka 8 Hours. The bike’s potential was underlined by good showings in the intensely competitive Japanese FI Championship and the Swann Series in Australia.

It was an open secret that this was the bike that would form the basis of the 1 989 street bike. And so it proved to be. The ZX-7 motor is a heavily modded Ninja powerplant with a completely new cylinder-head design and totally revised intake system. Rocker arms are out this year; the ZX-7 reverts to the direct-actuation, bucket-and-shim design favored by engineering purists. Air finds its way into the new head via a 6.4-liter airbox and 36mm downdraft carburetors, traveling through intake tracts hand-finished at the factory to taper smoothly from carb to cylinder

head. The new valvetrain means that the mixture gets an almost straight run to the cylinder and doesn’t have to cope with as much interference from the valve guides.

The claimed result is 107 horsepower at 10,500 rpm, with maximum torque arriving 1000 rpm lower.

The aluminum chassis follows the same practice as the ZX-10. A cast steering head is welded to two extruded side beams which connect it to the box-section swingarm pivot. The swingarm itself carries an overhead brace that features the first of several clever touches. The left rear of the brace is bolted to the arm, not welded, thus enabling an endless chain to be replaced without removing the entire swingarm.

The Unitrak shock linkage has needle roller bearings throughout and incorporates an eccentric bushing where the linkage rods pivot on the arm. Slacken the clamp and rotate this eccentric and you alter ride height.

That type of detail suggests serious racing potential, and Kawasaki is happy to admit that the rapidly growing popularity of Superbike racing outside of its usual strongholds of the USA and Australia was a major factor in the design of the ZX-7. Hoping to cash in on that popularity with the world’s street racers, Kawasaki has set the ZX-7’s price at $6299, cheaper than the very-limited-production, notavailable-in-the-U.S. RC30 by over $5000. But then it is also 5 horsepower down and about 70 pounds heavier than Honda’s banner carrier. In fact, the new ZX-7 is 30 pounds heavier than Suzuki’s GSX-R750 and even 25 pounds heavier than the old Ninja 750.

With that in mind, can it really be a Superbike contender? Kawasaki has faith; For the bike’s press introduction, it set 70 European journalists loose at the Estoril racetrack in Portugal, a circuit with a variety of corners, two good-length straights and enough bumps to give the suspension a real workout. Only the close proximity of large amounts of Armco barriers dampened enthusiasm.

The fastest lap of Estoril I can find in the record books is 1 minute, 39.97 seconds, set by a 500cc RG Suzuki Formula One bike in 1985. The fastest 250cc lap at the same meeting was 1 minute, 47.62 seconds. At the Kawasaki press launch, the fastest anyone got a standard ZX-7 around was 1 minute, 57 seconds. As Kawasaki left the bikes totally road-standard, down to the turnsignals and sidestands, that is far from shabby.

The track proved a few things beyond doubt. The ZX7’s semi-floating twin front discs and their four-piston calipers couldn’t be persuaded to fade, nor could the 17-inch Bridgestone Cyrox radiais be encouraged to misbehave, at least not at the fast, street-riding velocities that I attained. Thus reassured that a close encounter with the Armco was less than likely, I was able to discover another truth: The ZX-7’s top end is truly impressive. The 1500 revs between peak power and redline are surplus to requirements, providing a useful upwards kink in the otherwise flat torque curve.

After making a hash of one of Estoril's blind, late-apex corners, I realized that my life had been made considerably easier (and probably longer) by the ZX-7’s unimpeachably neutral steering. You want to lean over a little further? No problem, just put slightly more pressure on the bars and it’s done. Make a serious error due to enthusiasm outweighing ability, and feel that you really should shut off in a corner? You are immediately forgiven.

In short, this is another amazingly competent Japanese sportbike. Put next to an RC30, it acts like a roadster that could be turned into a racer, as opposed to a racer that’s had a lighting kit added. It feels like an FZR that’s had a course of steroids. Come to think of it, that's how it looks.

In order to become a serious contender in Superbike racing, the first thing it’ll have to do is diet. One of Kawasaki’s biggest engineering problems has always been noise—they aren’t very good at getting rid of it—so junking the efficient but heavy 4-into-2-into-1 exhaust system will lose a lot of poundage straight away. Kawasaki claims that the addition of a full race kit plus unbolting the rest of the street-legal necessities will lose 65 pounds. If true, that would only get it to within 5 pounds of a standard RC30.

Still, the professional racers getting their first taste of a ZX-7 at the Estoril intro were happier than they thought they’d be. After all, Kawasaki has never had any trouble finding power when it needs to. In street terms, it’ll be interesting to find out if the ZX-7 can summon up the midrange to punch out of a corner like a V-Four Honda or a well-sorted FZR, but it’ll need a test track and timing lights to settle that argument.

The racetrack argument will also have to wait. But Kawasaki is serious, as they’ve re-employed Frenchman Patrick Igoa, three times a world endurance champion with Honda, to lead the World Superbike challenge. Can he win? If a steel-framed Ninja 750 can, I should think so, although showing a rear fender to the Honda RC30s, the revised GSX-R750Rs and new Yamaha OWOls on a regular basis won’t be a walkover.

But with the ZX-7, Kawasaki has made a couple of things certain: All of the Japanese manufacturers now have a super-serious 750 sportbike, and for the first time in many a year we’re going to see the Big Four slug it out head-to-head in world-championship roadracing.

Julian Ryder is a British motor-journalist who currently lists his job description as “Editor, Publisher phone-answerer and tea-boy" at Road Racer magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSo Many Curves, So Little Time

April 1989 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeSilver Wing For A Silver Eagle

April 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsTen Percenters

April 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Spada: the Newest World Standard

April 1989 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupHailwood Ducati For Sale: $19,000

April 1989