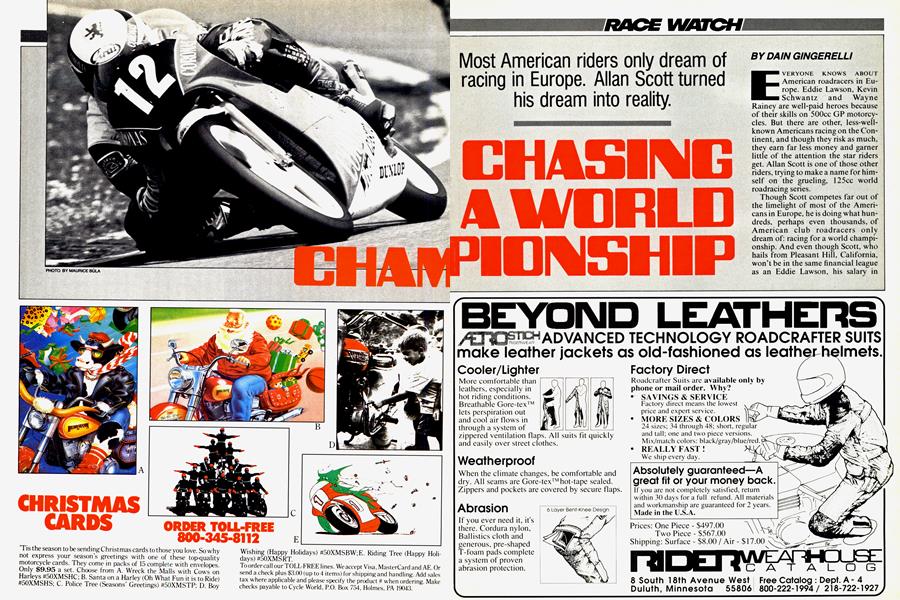

CHASING A WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP

RACE WATCH

Most American riders only dream of racing in Europe. Allan Scott turned his dream into reality.

DAIN GINGERELLI

EVERYONE KNOWS ABOUT American roadracers in Europe. Eddie Lawson, Kevin Schwantz and Wayne Rainey are well-paid heroes because of their skills on 500cc GP motorcycles. But there are other, less-well-known Americans racing on the Continent, and though they risk as much, they earn far less money and garner little of the attention the star riders get. Allan Scott is one of those other riders, trying to make a name for him self on the grueling, 125cc world roadracing series.

Though Scott competes far out of the limelight of most of the Ameri cans in Europe. he is doing what hun dreds, perhaps even thousands, of American club roadracers only dream of: racing for a world champi onship. And even though Scott, who hails from Pleasant Hill, California, won't be in the same financial league as an Eddie Lawson, his salary in 1990 will make it possible for him to concentrate on racing. That’s because the 24-year-old Scott, virtually unknown in America, has just signed a contract with the Spanish cigarette company Coronas for next season. Scott’s deal with Coronas wasn't just a matter of being in the right place at the right time. He paid his dues as a privateer, including three lean years in which he subsisted solely on his meager earnings from racing, not unusual for GP privateers.

The Allan Scott story actually begins in Scotland, where he was born. When Scott was just a year old, his father, Dave, packed up the clan and headed for California. As a former Scottish roadrace champion, the senior Scott became involved in the San Francisco Bay-area roadracing community that then constituted the hub of roadracing in the U.S. By 1970, Scott had earned the coveted AFM Number One plate, at the time perhaps the top honor—other than winning Daytona—a roadracer could earn in America.

Four years later, Scott crashed hard during a Sears Point race. Says the elder Scott, “I just gave up after that.” End of roadracing story, as far as anybody in the Scott family was concerned. Or so they thought.

By then, Allan and older brother David had acquired a sense of balance to match an inbred competitive spirit. Bicycle motocross led to real motocross, which soon led to roadracing, and David Jr. and Allan found themselves on the grid at Sears Point, waiting for the green flag to drop on their first pavement race.

At first, David Jr. showed the most promise, while Allan was building a reputation as a wild rider. His father testifies: “He wrecked a lot of bikes in the beginning. He was a tuner’s nightmare. He’d come in after practice never asking for changes. He’d just ride the bike to its limit.”

Obviously, though, Allan Scott began doing something right. By 1983, he captured the AFM 125cc GP championship. “Once I rode a 125,” he recalls today, “I wanted to go to Europe and become world champion.”

Scott got his first crack at the bigtime in August of 1986, when he was awarded an entry for the British GP after cutting through mountains of political red tape. But Scott’s GP debut was a failure: He didn’t qualify for the race. The FIM still allowed twin-cylinder engines in the 125 class then, and Scott’s EMC racer was powered by a single-cylinder Rotax, and, hence, severely outgunned by the Twins. Still, Scott forged ahead in 1987 with the EMC, knowing that in 1988, when a single-cylinder-only rule was to be implemented in the 125cc class, he would be on equal footing with everybody else.

Scott failed to qualify in his first five races of the ’87 season, but at the

French Grand Prix, he made the grid, going on to post his best finish of the year, a 13th.

Nineteen eighty-eight was a pivotal year for Scott. He showed up at the first race, the Italian GP, with all of $50 in his wallet. “That was the closest to quitting I ever got,” he says today. But he qualified for the race, earning enough money to continue on to the next event.

As in 1987, Scott’s performance in 1988 was littered with double-digit finishes. Finally, at the Belgian GP, he put his new Honda 125 within spitting distance of the victory podium, with a sixth-place finish. After a ninth at the following race in Yugoslavia, the racing world was beginning to take notice of Scott. Then, after qualifying eighth for the French GP, he crashed—with little damage to bike or rider-while running fourth.

The prospects for the remainder of the season appeared good for Scott and his mechanic/best friend Jeff Markus. Or so it seemed, when, on his way from France to England for the British GP, his racing career stared catastrophe in the face. The Allan Scott Racing van, a Ford Econoline of 1969 vintage, caught fire when a rear wheel came loose, and, as the van skidded to a halt, friction from the pavement ignited some grease. Help arrived in time to douse the flames before his race equipment was burned, but sparks had ignited a

nearby farmer’s field.

“After that fire was out,” jokes Scott today, “the police questioned me. They took me to jail because they wanted to put the blame (for the field fire) on me. Pius they wanted to take all my money to pay for the damage.” Following a lot of head nodding, hand waving and shoulder shrugging, Scott cut a deal with the police: “They kept the van. It wasn’t worth much anyway, but it left me without a ride to England.”

As events unfolded, several other 125-class riders volunteered to haul his equipment to Donington for the GP. And Honda of Great Britain also loaned Scott a van for the week, so total calamity was avoided.

However, Scott’s troubles didn’t end at the French border. Awaiting them in England was a customs official who felt loyal to both the Queen and Parliament. Essentially, the cus-

toms official wouldn’t let Markus, who holds an American passport, enter the UK because he was a worker for Scott (who holds a British passport). The official reasoned that Markus was depriving some poor, starving, unemployed British citizen of the chance of going to Donington to tune for Scott. After much bickering, the matter was straightened out,

allowing Scott and Markus to carry on to the racetrack.

Scott responded with a fifth at Donington, and, followed by a 10th at the Czech GP, he was rated 12th overall for the 1988 season. He also gained the attention of a few sponsors, including Jyohoku (better known as JHa), an exhaust-pipe builder from Japan, as well as Arai Helmets and Castrol Oil.

Scott charged head-on into the 1989 season, but a disappointing 13th at the season opener in Japan brought new doubts about his program. He responded at the Australian GP with a third-place finish, marking his first visit to victory circle. By season’s end, Scott had accumulated enough points to rank him 10th overall in the class. More to the point, he gained the attention of Coronas following his front-row qualifying at the Spanish GP. With Coronas’ backing for 1990, Scott’s immediate future in racing seems secure. In fact, some big companies are taking notice.

Recently, the Italian motorcycle conglomerate Cagiva invited Scott and some other riders to a trial session aboard the same red racer that Randy Mamola has ridden the past two seasons. The riders included GP veterans Kevin Magee and Ron Haslam. In short, Magee was fastest, followed by Haslam. Scott, with no previous 500 experience, was three seconds off the pace. And even if Scott isn’t given a factory ride with Cagiva, he feels the 94 laps he spent on the bike were valuable experience. He says, “I think that with a little time, I could ride it (a 500) fast.”

With the 1990 race season just around the corner, one thing’s for certain, though: Scott won’t have to dip into his own pocket to pay for his racing. His apprenticeship is over. Now, it’s time to get on with the job at hand; the job, according to Scott, of winning a world championship, no matter what class he’s in. A big goal, to be sure, one that dreamers only dream of, while believers make happen. Believers such as Eddie Lawson . . . and maybe even Allan Scott, s

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWelcome Back, Honda

December 1989 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeThe Year of Riding Dangerously

December 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Museum of Prehistoric Helmets

December 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1989 -

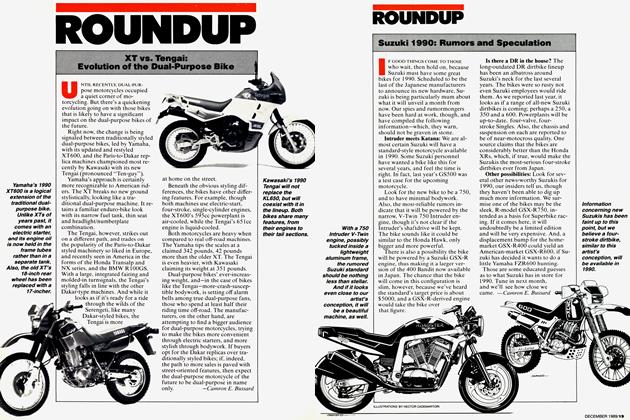

Roundup

RoundupXt Vs. Tengai: Evolution of the Dual-Purpose Bike

December 1989 By Camron E. Bussard -

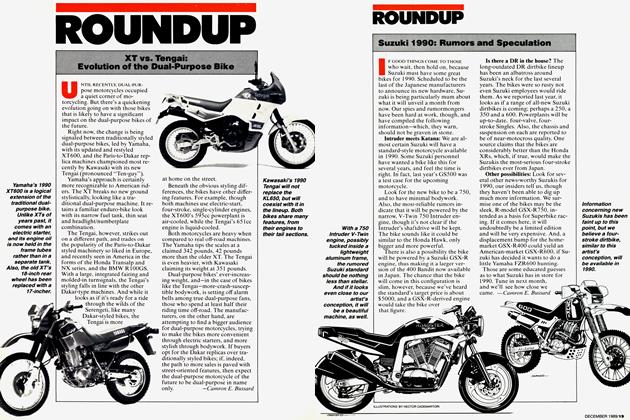

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki 1990: Rumors And Speculation

December 1989 By Camron E. Bussard