AT LARGE

Progress report on Proposition K

Steven L. Thompson

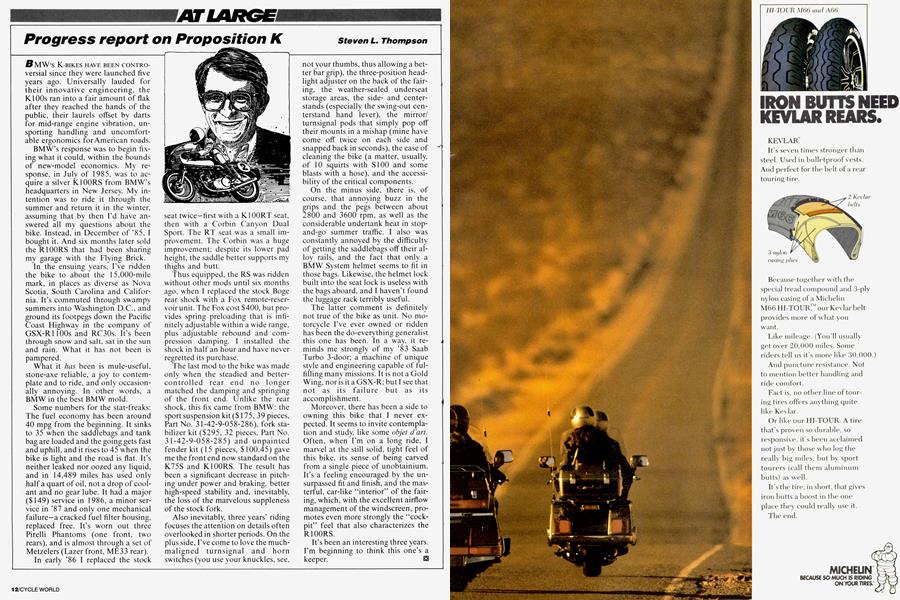

BMW's K-BIKES HAVE BEEN CONTROversial since they were launched five years ago. Universally lauded for their innovative engineering, the K100s ran into a fair amount of flak after they reached the hands of the public, their laurels offset by darts for mid-range engine vibration, unsporting handling and uncomfortable ergonomics for American roads.

BMW’s response was to begin fixing what it could, within the bounds of new-model economics. My response, in July of 1985, was to acquire a silver K100RS from BMW’s headquarters in New Jersey. My intention was to ride it through the summer and return it in the winter, assuming that by then I’d have answered all my questions about the bike. Instead, in December of ’85, I bought it. And six months later sold the R100RS that had been sharing my garage with the Flying Brick.

In the ensuing years, I’ve ridden the bike to about the 15,000-mile mark, in places as diverse as Nova Scotia, South Carolina and California. It’s commuted through swampy summers into Washington D.C., and ground its footpegs down the Pacific Coast Highway in the company of GSX-R 1100s and RC30s. It’s been

through snow and salt, sat in the sun and rain. What it has not been is pampered.

What it has been is mule-useful, stone-axe reliable, a joy to contemplate and to ride, and only occasionally annoying. In other words, a BMW in the best BMW mold.

Some numbers for the stat-freaks: The fuel economy has been around 40 mpg from the beginning. It sinks to 35 when the saddlebags and tank bag are loaded and the going gets fast and uphill, and it rises to 45 when the bike is light and the road is flat. It’s neither leaked nor oozed any liquid, and in 14,489 miles has used only half a quart of oil, not a drop of coolant and no gear lube. It had a major ($149) service in 1986, a minor service in ’87 and only one mechanical failure—a cracked fuel filter housing, replaced free. It’s worn out three Pirelli Phantoms (one front, two rears), and is almost through a set of Metzelers (Lazer front, ME33 rear).

In early ’86 I replaced the stock seat twice—first with a K100RT seat, then with a Corbin Canyon Dual Sport. The RT seat was a small improvement. The Corbin was a huge improvement; despite its lower pad height, the saddle better supports my thighs and butt.

Thus equipped, the RS was ridden without other mods until six months ago, when I replaced the stock Boge rear shock with a Fox remote-reservoir unit. The Fox cost $400, but provides spring preloading that is infinitely adjustable within a wide range, plus adjustable rebound and compression damping. I installed the shock in half an hour and have never regretted its purchase.

The last mod to the bike was made only when the steadied and bettercontrolled rear end no longer matched the damping and springing of the front end. Unlike the rear shock, this fix came from BMW: the sport suspension kit ($175, 39 pieces, Part No. 31-42-9-058-286), fork stabilizer kit ($295, 32 pieces, Part No. 31-42-9-058-285) and unpainted fender kit ( 15 pieces, $ 100.45) gave me the front end now standard on the K75S and K100RS. The result has been a significant decrease in pitching under power and braking, better high-speed stability and, inevitably, the loss of the marvelous suppleness of the stock fork.

Also inevitably, three years’ riding focuses the attention on details often overlooked in shorter periods. On the plus side, I’ve come to love the muchmaligned turnsignal and horn switches (you use your knuckles, see, not your thumbs, thus allowing a better bar grip), the three-position headlight adjuster on the back of the fairing, the weather-sealed underseat storage areas, the sideand centerstands (especially the swing-out centerstand hand lever), the mirror/ turnsignal pods that simply pop off their mounts in a mishap (mine have come off twice on each side and snapped back in seconds), the ease of cleaning the bike (a matter, usually, of 10 squirts with SI00 and some blasts with a hose), and the accessibility of the critical components.

On the minus side, there is, of course, that annoying buzz in the grips and the pegs between about 2800 and 3600 rpm, as well as the considerable undertank heat in stopand-go summer traffic. I also was constantly annoyed by the difficulty of getting the saddlebags off their alloy rails, and the fact that only a BMW System helmet seems to fit in those bags. Likewise, the helmet lock built into the seat lock is useless with the bags aboard, and I haven’t found the luggage rack terribly useful.

The latter comment is definitely not true of the bike as unit. No motorcycle I’ve ever owned or ridden has been the do-everything generalist this one has been. In a way, it reminds me strongly of my ’83 Saab Turbo 3-door; a machine of unique style and engineering capable of fulfilling many missions. It is not a Gold Wing, nor is it a GSX-R; but I see that not as its failure but as its accomplishment.

Moreover, there has been a side to owning this bike that I never expected. It seems to invite contemplation and study, like some objet d'art. Often, when I’m on a long ride, I marvel at the still solid, tight feel of this bike, its sense of being carved from a single piece of unobtainium. It’s a feeling encouraged by the unsurpassed fit and finish, and the masterful, car-like “interior” of the fairing, which, with the excellent airflow management of the windscreen, promotes even more strongly the “cockpit” feel that also characterizes the R100RS.

It’s been an interesting three years. I’m beginning to think this one’s a keeper.