PARIS TO DAKAR,1988

RACE WATCH

RON LAWSON

PAUL BLEZARD

IN TEN YEARS. THE PARIS-To-

Dakar Rally has grown from

an obscure North African ad-

venture for a few crazy

Frenchmen to the toughest and bestknown motor rally in the world. In Europe, the event is like the Superbowl. the Indy 500. Daytona Speedweeks and the presidential elections all rolled into one.

The 1988 edition of the P-to-D was intended to be a joyful 10thanniversary celebration, a fitting tribute to its creator, the late Thierry Sabine. But that’s not what happened. Instead, it became one of the most widely criticized events in the history of mo tors ports.

Not that this rally is a stranger to death: 23 people had died in the previous nine rallies. But this year's event was the most disastrous ever. After three weeks and 8000 miles, seven people w'ere dead. 33 were seriously injured, and the future of the rally was in serious question.

What went wrong?

Things started well enough. The rally attracted more competitors than ever before, with nearly 1000 racers spread between 329 cars, 1 19 trucks and 193 bikes, sidecars and fourwheel ATVs. There was massive sponsorship from Pioneer, backed up by Paris-Match magazine and CocaCola. Including all the sponsorship behind the entrants, and the cost of their vehicles, some $100,000,000 was tied up in the rally. And European TV and radio coverage promised to be the best ever.

The ultimate adventure turns into a North African nightmare

But behind the scenes, trouble was brewing even before the rally started. The Thierry Sabine Organization had been rocked some months earlier when most of Sabine’s closest associates left the organization to promote the Trans-Amazonas rally in North and South America. That left Sabine's 62-year-old father. Gilbert, to hold the Paris-to-Dakar event with only a handful of the original players.

There also were problems with the routing in Algeria, and only the lastminute intervention of the French minister of the interior persuaded the Algerian government to let the rally proceed. Gilbert Sabine admitted that he had very nearly called the whole thing off.

After the first leg of the rally, many of the riders probably wished he had. The going was incredibly difficult. and by the half way mark at Agadés, more than two-thirds of the entrants were already out of the rally, a truck and a car competitor were dead, and former World Motocross Champion André Malherbe had been left paralyzed after a frightful crash. There also was another paralysis, three serious chest injuries and over a dozen broken bones. As a consequence, the event provoked a chorus of criticism around the world.

Jean-Marie Balestre. president of the car-sanctioning body, the FISA, waded in with the first of many pronouncements. “This year the organizers have distanced themselves from the original philosophy of the event in transforming it into a flatout sprint. For Dakar to keep its significance, we must confront the power of money with strict rules.” There was critisism from long-time friends of the rally, too. Mano Dayak, a personal friend and guide to Thierry Sabine, said that the Dakar seemed to have lost its friendly charm. “There’s too much talk about business and advertising. The organization must recapture the sprit that existed two or three years ago.” Jean-Claude Olivier, who had been riding near Malherbe when the former world champion had his accident, complained about the late starts and the long stages that forced most of the motorcyclists to ride for hours in the dark every night. Twotime motorcycle winner Hubert Auriol, who followed the race as an observer after breaking his buggy in the first special test, said that the race had become a “crash pump.” He claimed that no one at the promoting organization really understood bike racing, and that night sections were supposed to be forbidden in the rally. Five-time winner Cyril Neveu agreed. “The bikes arrive too often at night and they’re sick of it. This is not a rally for bikes anymore.”

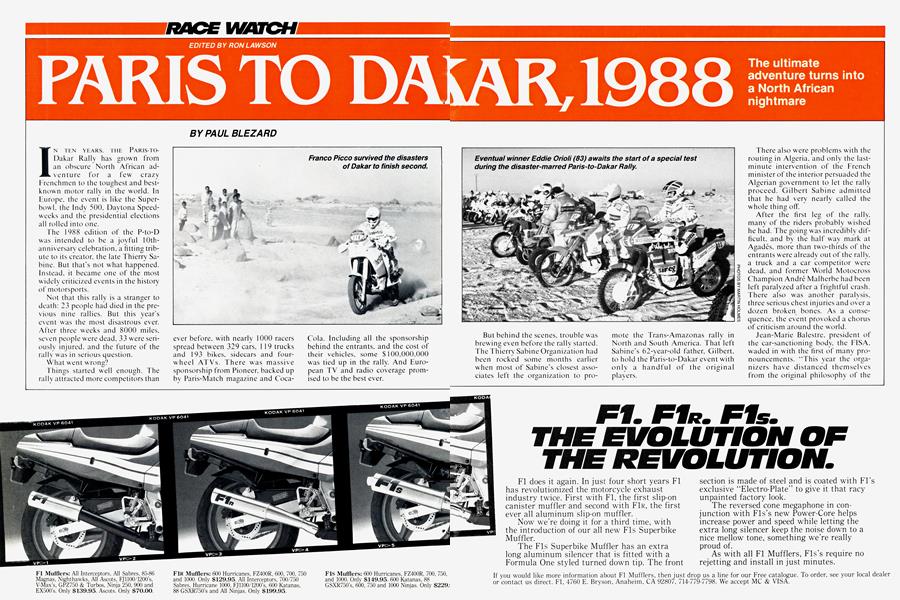

In the meantime, the rally—and its trou bl es—continued. On January 1 Oth, a mechanic was run over while sleeping in the camping area. Two days later. Neveu crashed and broke his foot, knocking him out of the event. Early leader Gaston Rahier also was involved in a early crash, and then had engine trouble. He remained in the rally, but his chances of a win were gone, while Hondamounted Eddie Orioli of Italy developed a lead over Franco Picco.

Several factors seemed to climax around the 13th of January. In the Vatican’s newspaper, the Pope criticized the rally for its gross commercialism and waste of life. By that time, entire organizations had been formed to attempt the stoppage of the rally. The most powerful was the Pa’Dak, an association of 250 groups opposed to the rally. On top of that, an influential French environmental group called SOS Environment, sort of a French equivalent of the Sierra Club, called on governments not to allow passage of the competitors. The Mali government did just that for half a day on the 13th, and it took high-level pressure from French diplomats to allow the rally to continue.

The list of problems got longer and longer. There was crisis after crisis dealing with fuel for the rescue aircraft. disruption from sandstorms, and problems with the course directions. No less than six control points marked in the road book turned out not to exist. Of the planned 17 special tests, five were cancelled or neutralized during the event.

Worse yet. the death toll rose still higher. In addition to two car drivers killed earlier, motorcyclist JeanClaude Huger crashed on the 1 7th of January and died two days later without regaining consciousness. On the 18th, a 10-year-old African girl was hit and killed by a Toyota in a dust storm, bringing the total number of deaths to four at that point.

But the rally continued, with Orioli holding out for the win. Even on the last two days of the event, though, the glow of his victory was overshadowed by more death. A mother and daughter were killed by an errant camera car, and a little girl was crushed to death when one of the posts holding the finish banner fell on her in Dakar.

It was clear, even to Gilbert Sabine, that the casualties had gotten far out of hand. He admitted that many mistakes had been made. “We accepted too many entries and allowed too many people to follow the rally. There were too many mechanics and too many tourists. We must limit the support behind each team at all levels, and see about revising the regulations.” He also promised the route would be better balanced, without being less difficult. “I sincerely regret the way things went in the first stage, which destabilized the rally. Next year, the stages will be more progressive.”

As to the exclusion of motorcycles altogether, as proposed by the FISA, Sabine said, “If bikes are banned from the Dakar, then there won’t be another Dakar. It’s the bikes that have made the Dakar famous. The representatives of the sport should think about the importance of longdistance rallies; they are the future for motorized sports. But I want to get back to a more human Dakar, closer to the original spirit.”

But whether or not there will even be another P-to-D rally seems highly in doubt at this time. As if to answer his critics, Sabine said, “I intend to organize a round table with all the interested parties. We have to think it over, to see if the game is worth the candle. Right now I’m not sure of anything.” But later he said, “I will do everything in my power to ensure that the Dakar continues.”

Before his death, Thierry Sabine himself said that the 10th Paris-Dakar should be the last; he may yet turn out to be right. One thing seems certain, though: With the incredible popularity of the rally in Europe among individuals and corporations, some sort of rally will spring up to take its place.

What will it be? Well, there’s already talk of a Paris-to-Peking rally.