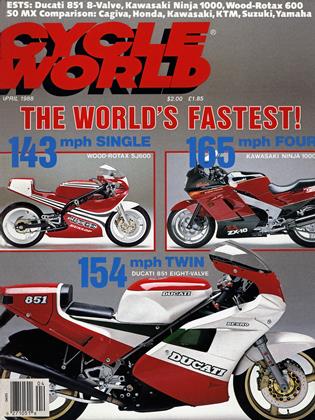

SuperSingle

Faster than a 600 Hurricane. AS quick as most 750s. All on just one cylinder.

STEVE ANDERSON

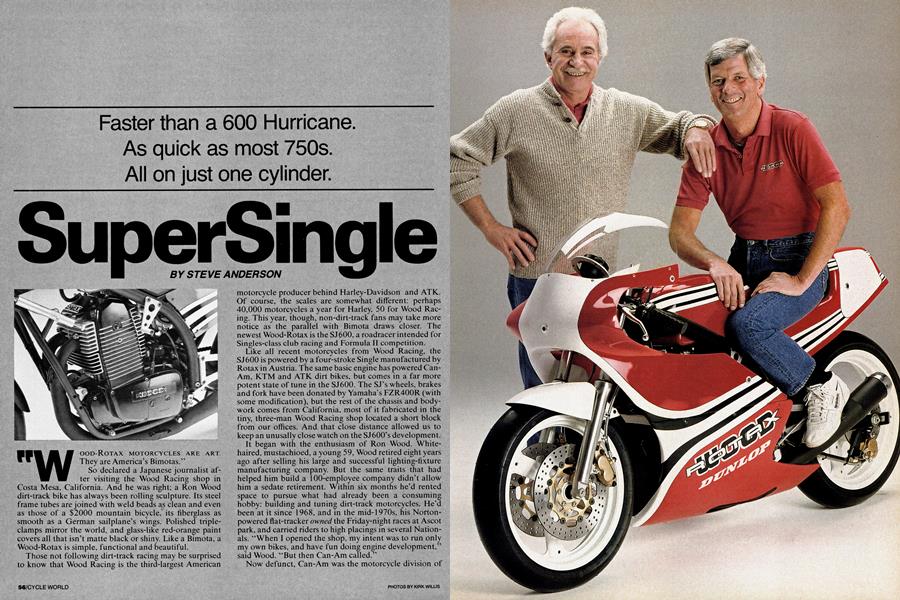

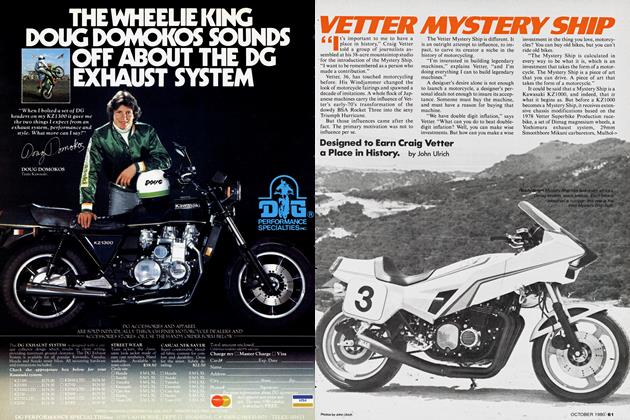

"WOOD-ROTAX MOTORCYCLES ARE ART. They are America’s Bimotas.” So declared a Japanese journalist after visiting the Wood Racing shop in Costa Mesa, California. And he was right; a Ron Wood dirt-track bike has always been rolling sculpture. Its steel frame tubes are joined with weld beads as clean and even as those of a $2000 mountain bicycle, its fiberglass as smooth as a German sailplane’s wings. Polished triple-clamps mirror the world, and glass-like red-orange paint covers all that isn’t matte black or shiny. Like a Bimota, a Wood-Rotax is simple, functional and beautiful.

Those not following dirt-track racing may be surprised to know that Wood Racing is the third-largest American motorcycle producer behind Harley-Davidson and ATK. Of course, the scales are somewhat different; perhaps 40,000 motorcycles a year for Harley, 50 for Wood Racing. This year, though, non-dirt-track fans may take more notice as the parallel with Bimota draws closer. The newest Wood-Rotax is the SJ600, a roadracer intended for Singles-class club racing and Formula II competition.

Like ail recent motorcycles from Wood Racing, the SJ600 is powered by a four-stroke Single manufactured by Rotax in Austria. The same basic engine has powered CanAm, KTM and ATK dirt bikes, but comes in a far more potent state of tune in the SJ600. The SJ’s wheels, brakes and fork have been donated by Yamaha's FZR400R (with some modification), but the rest of the chassis and bodywork comes from California, most of it fabricated in the tiny, three-man Wood Racing shop located a short block from our offices. And that close distance allowed us to keep an unusally close watch on the SJ600’s development.

It began with the enthusiasm of Ron Wood. Whitehaired, mustachioed, a young 59, Wood retired eight years ago after selling his large and successful lighting-fixture manufacturing company. But the same traits that had helped him build a 100-employee company didn't allow him a sedate retirement. Within six months he’d rented space to pursue what had already been a consuming hobby: building and tuning dirt-track motorcycles. He'd been at it since 1968, and in the mid-1970s, his Nortonpowered flat-tracker owned the Friday-night races at Ascot park, and carried riders to high placings in several Nationals. “When I opened the shop, my intent was to run only my own bikes, and have fun doing engine development,” said Wood. “But then Can-Am called.”

Now defunct, Can-Am was the motorcycle division of the Canadian-based Bombardier company; Rotax was, and still is, the engine division, and was just finishing development of a new four-stroke Single for Can-Am motorcycles. The Can-Am people wondered if the new engine could draw some publicity in American dirt-track racing. Would Mr. Wood perhaps like to see what he could do with some prototype engines?

One thing led to another, and Wood Racine soon was the Ü.S. distributor of four-stroke Rotax racing engines, and was making and selling complete dirt-track bikes. Wood’s hobby had turned into another business.

Wood is the first to admit that none of this would have come to pass without Steve Jentges (pronounced JEN-is), Wood Racing’s chief fabricator. Jentges is an artist who happens to work in metal, whose credentials reach back to work on Indy-car chassis in the 1960s. In the 1970s he became known to the motorcycle world as the “J” in C&J frames. That’s where Ron Wood first met him: C&J built the frames for Wood’s dirt-track Nortons. In 1979, Jentges left C&J to work for a small, high-tech machine shop, where he did things like build wind-tunnel models for various aerospace companies. When Wood got word that Jentges wasn’t happy there, he hired him immediately. Even now, Wood says. “If Steve were ever to leave, I’d just quit making frames.”

That’s an easy sentiment to understand if you’ve seen Jentges at work. Slight, shoulders hunched forward, as light on his feet as a cat, he is so quiet he seems to blend into the shop background. But he sparkles with enthusiasm when he thinks of something new to make, something that can test his considerable skills. In three days he built the original gas tank for the SJ600 from aluminum sheet, a masterpiece of compound curves and invisible seams. He’s a perfectionist whose welding skill produces the loveliest joints to be found. He’s not satisfied with a frame unless engine and swingarm-pivot bolts slide into their veryclose-tolerance holes unforced. And for every part that Jentges makes, he builds simple fixtures and jigs so that the next can be not just as good, but better.

I The SJ600 took shape as a collaboration between those two: Wood, the dirt-track tuner with 20 years of experience designing and racing motorcycles, and Jentges, the master fabricator who had built frames for everything. The depth of Wood's admiration and respect for Jentges’ skill can be found in the bike’s designation: The “SJ” in SJ600 stands for Steve Jentges.

Why a roadracer? Wood explains: ‘T kept getting calls from guys who wanted to buy my dirt-track frame for roadracing. But it wasn’t designed for that; it’d probably be a real flexi-flyer on pavement. And my dirt-track ket gets smaller every year as the number of races and license-holders drop. I thought that a roadracer would give me a stable market with a bike that could be sold in the U.S., in Europe, and especially in Japan, where Singles racing is very popular.

“It’s designed as a club racer,” he continues. “It’s for someone who’s maybe 25 to 40 years old, who has some money. He’s maybe 5 feet 1 1 and weighs 165 pounds. He wants to race 12 to 15 times a year, and without the maintenance hassles of a two-stroke. And he probably doesn’t want to go as fast as an 1100 multi will take him.”

The SJ600’s frame first took shape on Wood’s drawing board, with the engine location (low and forward) and the wheelbase (short) the first parameters. He freely admits that 250cc GP bikes were his model for weight distribution and steering geometry, and that he took measurements from Honda, Yamaha and Cobas-Rotax 250s before he designed his chassis.

But while the SJ600 may share some characteristics with these bikes, the basic frame is very different indeed. First, it’s made of chrome-moly steel, a material both Wood and Jentges know well, and trust. Neither is impressed with the strength of aluminum frames built without a post-weld heat treatment. Wood says simply, “A steel frame can be as strong, as stiff, and probably lighter than an aluminum frame.” With a weight of 16 pounds, the SJ600 frame goes a long way toward proving his point.

The second difference is almost a Ron Wood trademark: He has embraced complexity in frame manufacture to achieve simplicity in the finished product. The Rotax engine uses a dry sump and requires a remote oil tank, so on the SJ600, that tank is built into the frame as a massive reinforcement for the steering head. But rather than run long hoses from engine to tank, Wood uses the frame itself for oil lines. The right downtube carries oil from the sump up to the tank (where an internal tube squirts it past the oil

filler opening, for easy confirmation that the oil pump is working); the large, main frame tubes (the very bottoms of which act as sediment traps) carry oil back to a cross tube, and from there to the engine. The result is just eight inches of rubber oil lines instead of the typical six feet, and no need for an external oil cooler; the large frame area exposed to oil flow serves instead.

Originally, the SJ600 used a twin-shock rear suspension, just like as the Wood-Rotax dirt-trackers. In that form, with an aluminum gas tank and seat, the bike first ran in the 1987 Daytona Formula II race. Completed barely a week before the race, this prototype SJ used a 500cc five-speed dirt-track engine to comply with last year’s Formula II displacement limits. Piloted by dirttracker Chris Carr, the SJ handled and worked well; but due to a lack of power and rider experience, it was 12 seconds off the leader's pace. With a 140-mph trap speed, it was a ver>' fast Single, but more than 10 mph down on the fastest two-strokes.

This less-than-auspicious Daytona debut was followed by a club-race appearance with Formula II pilot Andy Leisner at the helm. Without the restriction of AMA rules, a 600cc engine boosted the power to winning levels. Only some rear-suspension chatter over small ripples proved a minor problem.

Shock-absorber modifications would probably have cured the chatter, but Wood was already contemplating a switch to a single-shock rear suspension. That would allow a narrower seat section, something that everyone who rode the bike wanted, and, important for sales, would give the bike a more modern appearance. After conferences with suspension experts, the rear subframe was removed and Jentges began fabricating an asymmetric, no-linkage, oneshock setup, much like BMW’s Monolever arrangement, but on a normal swingarm.

Unfortunately, it never worked. No matter who rode the bike, and no matter which brand of shock was used, the new suspension proved a step backward. It was either too soft, or too stiff, or too chattery, and no amount of spring changes, damping changes and swingarm bracing seemed to help.

While even the experts couldn’t explain the problem with the offset monoshock. Wood was moving ahead and looking at linkage-type designs used on Japanese motorcycles. The system on Yamaha's FZ600 was well-regarded and could easily fit the SJ600’s frame; soon, Jentges was cutting and welding again.

This third rear suspension has proven to be the best. Compact, with the shock tucked behind the engine, it allows a very light and narrow rear sub-frame. And after much tuning of the Fox shock itself, the final result is a rear suspension that no longer intrudes on the rider’s concentration.

As the suspension shaped up to Wood’s satisfaction, the final issue he addressed was the bodywork. The original aluminum tank and seat were simply an expedient; the intent was always to offer the production machine with fiberglass components, ones that satisfied Wood’s high standards of quality and style. The means to that end were surprisingly direct; He mounted blocks of styrofoam (the type used to make surfboards) in place of tank and seat, and began sculpting. After two weeks of tedious work, including days of filling and sanding for a smooth surface finish, Wood had finished models of his tank and seat.

These were then used by Tom Teilefson, a moonlighting plastics engineer, to make molds and finished parts. Like everyone else involved in the project, Teilefson brings an unlikely amount of skill and knowledge to the production of a few motorcycle parts; he makes his real living consulting with the likes of aircraft companies on the manufacture of composite parts. His finished gas tank looks more like a factory metal tank but weighs a feathery, 3.5 pounds, far lighter than even aluminum could be. And Teilefson uses an unusually flexible and rugged aircraftapproved resin that’s proven capable of surviving years of dirt-track abuse.

In the end, the final result of all these efforts is a 262 pound Thumper that goes faster than any Thumper before, looks prettier than any racebike should, and reflects years of racing experience. That breeding shows in small things like the minimal effort required to remove the solidly mounted fairing: Undo three Dzus fastners per side, and the belly pan drops free. Pull two hairpin clips on each side, spread the fiberglass slightly, and the upper fairing lifts up and away. The entire operation might take 40 seconds if you were slow. Ten seconds more and you can have the gas tank off and be at the engine. Ron Wood may not have built a roadracer before, but he knows what’s important in any form of racing.

Production of the first 10 SJ600s has just begun, with four of them already spoken for. The price will be $ 10,000 for the bike as seen here but in unassembled, unpainted form, with a standard 600cc racing Rotax engine producing close to 60 horsepower at the rear wheel. There will be plenty of opportunties to spend more money: Wood offers his customers the same porting and engine components that he runs in his own private race engines, and $2500 more will bring engine output closer to 70 horsepower. Perhaps this pricing just brings the Bimota analogy closer: If you want this level of quality in a limited-production bike, you’ll have to pay for it.

Any version of the SJ600 is capable of dominating Singles-class club races; Wood’s bike has lapped Willow Springs at 1:33.2, more than five seconds faster than any other Single, and a reasonably competitive time in clublevel Formula II races. Whether it can be competitive in National Formula II races is another matter. The AMA is allowing 600cc Singles to run against the 250cc Twins in 1988, a change that makes competitive racing between the two at least conceivable. But the Honda RS250s and Yamaha TZs are powerful and light, the result of years of Grand Prix development. They also have the best riders. But every time the SJ600 has set tire on track recently it has gone faster; and come Daytona, Ron Wood will have a very special SJ600 to tilt at the two-stroke windmills.

In all likelihood, the SJ600 won’t win. But we’re sure there will be more than one two-stroke rider who’ll be shocked on the Daytona banking, surprised by the boom of a four-stroke Single passing him by. IS

Wood-Rotax

SJ600

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

April 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

April 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Departments

DepartmentsLeanings

April 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupYen And the Art of Motorcycle Marketing

April 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1988 By Kengo Yagawa