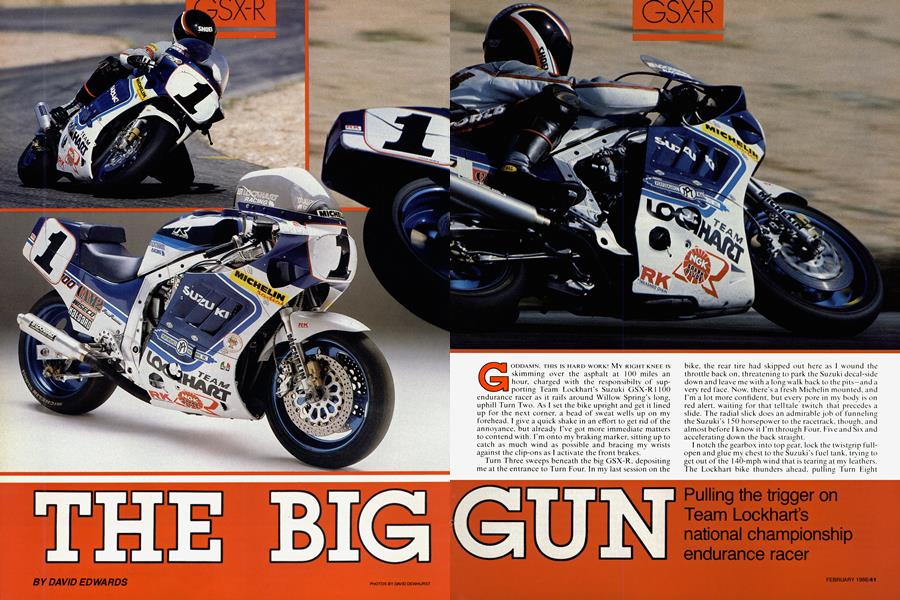

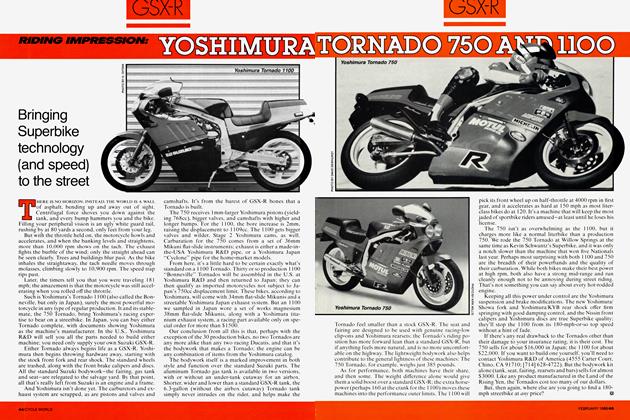

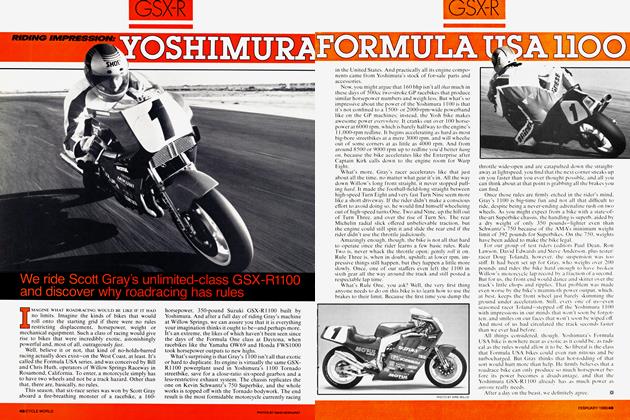

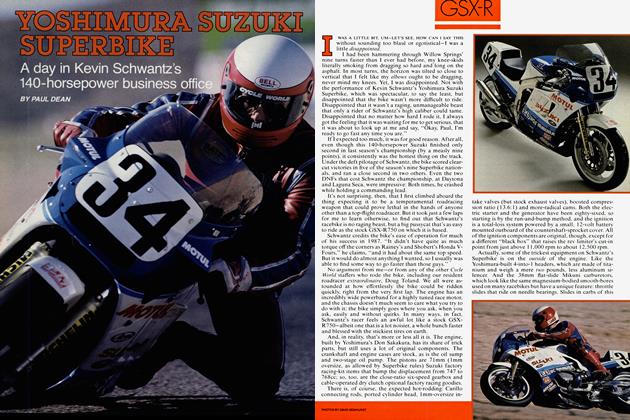

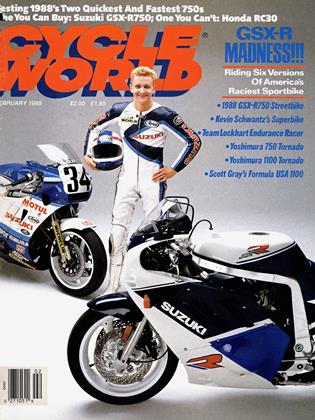

THE BIG GUN

GSX-R

DAVID EDWARDS

Pulling the trigger on Team Lockhart’s national championship endurance racer

GODDAMN. THIS IS HARD WORK! MY RIGHT KNEE IS skimming over the asphalt at 100 miles an hour, charged with the responsibilty of supporting Team Lockhart’s Suzuki GSX-R1100 endurance racer as it rails around Willow Spring's long, uphill Turn Two. As I set the bike upright and get it lined up for the next corner, a bead of sweat wells up on my forehead. I give a quick shake in an effort to get rid of the annoyance, but already I’ve got more immediate matters to contend with. I’m onto my braking marker, sitting up to catch as much wind as possible and bracing my wrists against the clip-ons as I activate the front brakes.

Turn Three sweeps beneath the big GSX-R, depositing me at the entrance to Turn Four. In my last session on the bike, the rear tire had skipped out here as I wound the throttle back on, threatening to park the Suzuki decal-side down and leave me with a long walk back to the pits—and a very red face. Now, there’s a fresh Michelin mounted, and I'm a lot more confident, but every pore in my body is on red alert, waiting for that telltale twitch that precedes a slide. The radial slick does an admirable job of funneling the Suzuki’s 1 50 horsepower to the racetrack, though, and almost before I know it I’m through Four, Five and Six and accelerating down the back straight.

I notch the gearbox into top gear, lock the twistgrip fullopen and glue my chest to the Suzuki's fuel tank, trying to get out of the 140-mph wind that is tearing at my leathers. The Lockhart bike thunders ahead, pulling Turn Eight into view at an alarmingly fast rate.

Wait, wait, wait. Now!

I pop out of the still air behind the fairing's bubble and simultaneously roll back the throttle, only to be greeted by a Turn Eight that I've never seen before. I've entered this sweeping corner hundreds of times in the past, but never this fast, never this close to The Edge. The turn looks much more narrow' now; I can't pick up my ususal reference points. I fight back the edges of panic, resist the urge to pounce on the brakes and scrub oflfspeed. Instead, with as tight a grip as I've ever inflicted on a set of handlebars, I pitch the bike to the right, and marvel at whatever combination of physics and black magic it is that allows a motorcycle to be leaned over this far. going this fast.

* * *

Back in the pits, I quickly drain the bright green contents of a Gatorade bottle. So, this is w hat happens when a hobby growls out of proportion. I think to myself. Back in 1984, if you knew Wendell Phillips at all, it was for a pretty extensive line of oil coolers put out by his company, Lockhart. That year, he also decided to go endurance roadracing on a Kawasaki Ninja 900. Three years later. Lockhart is one the country's largest aftermarket firms, with a 120-page catalog chock full of go-fast, look-good items for the sportbike crowd. The Ninja 900 racebike is longgone, replaced by a GSX-R 1 100 that has become a combination rolling showcase and test mule for the Lockhart line of products, a blue-and-white billboard that also happens to be capable of 180 miles an hour on a racetrack—and the holder of the 1986 and 1987 AMA National Endurance Championships.

Phillips doesn't ride the racer anymore, since the competition in the AMA endurance series—threeto four-hour events that cover 500 kilometers (310 miles)—is such that genuine throttle-jockies are needed to bring home a national title. In 1987 that task was placed in the talented hands of Larry Shorts and Dale Quarterly, who won six of the 1 2 races they entered. Quarterly, a 26-year-old charger w;ho also runs Pro Twins and Superbikes, quickly dispelled any notions I might have had that endurance racing is a genteel sport for cagey strategists, riders who plug into a conservative pace and ride it out for the duration.

“When the green flag drops," he tells me, “you go. At most tracks our lap times are a just a couple of seconds slower than the Superbikes’. When it comes to pit stops, you have to be in and out in 10 seconds or you’ll be dust. We take on seven gallons of gas in about five seconds. We're really not running endurance races anymore; they’re full-on sprint races."

* * *

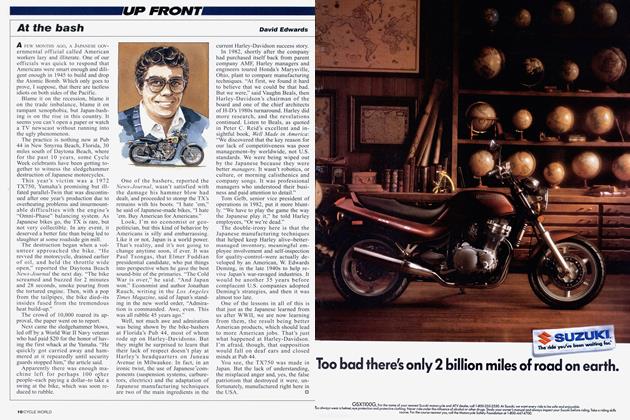

Even resting on its prop stand, waiting for my next turn at its controls, the Lockhart bike looks menacing, an armor-plated GSX-R with a built-in 80-mph tailwind. Team members refer to the bike as the “Big Gun,” and it's not hard to see how they came up with the name.

Keith Perry, Team Lockhart's crew chief, is fretting over his bike, running hands over the rear tire, checking chain tension, snooping for an oil leak or a loose nut. Phillips credits his crew chief with a good portion of the team's success over the past two years. “The key is 100 percent preparation,” he says. “Racetracks are for racing. We try to get all our testing done beforehand so that at the track all we have to do is put gas in and go." Quarterly breaks in and clarifies: “Most of the time this year, we could have started the bike in the back of the van, w heelied through the doors and begun the race."

Before coming over to Lockhart, Perry wrenched Team Ontario to the 1985 national endurance championship; and since I've got to toss his creation into Turn Eight a few more times this afternoon. I'm glad to see that Perry is hovering over the GSX-R as if it were about to roll out to the starting grid with the season on the line.

Later, Perry goes over the bike's technical details with me, and I'm surprised to discover that there's a lot of stock GSX-R beneath those Number One numberplates. All the bodywork is off-the-shelf stuff, although various ducts and gills have been carved into the fairing’s surface. The standard fuel tank has been enlarged by utilizing the space -normally occupied by the streetbike’s airbox, and a quickfill fitting has been grafted onto its top.

More surprisingly, the frame and swingarm are just as they left Suzuki's Hamamatsu production line, with no strengthening or gusseting whatsoever. Likewise, the fork tubes are stock, although the springing and damping have been fettled with, and the electric anti-dive system has been clipped. The fork mates to the steering head via Kosman triple-clamps, which offer strength and frontwheel-trail adjustability over the regular-issue assembly. A Dutch-made White Power rear shock replaces the stock damper, and attaches to a ride-height-adjustable linkage arm that Perry had machined out of billet aluminum.

The old racing axiom, “You've got to finish to win’’ is never more apparent than in endurance competition. Blazing to the lead at the two-hour mark doesn’t do much good if you’ve got to nurse an ailing motor for the next hour-and-a-half. So Perry is fairly restrained when it comes to engine modifications. He uses a standard GSX-R crankshaft that is first magnafluxed, polished and balanced. Stock connecting rods are attched to stock, lmmoversize pistons, though the team did experiment with Wiseco pistons at the end of the season. The ports get cleaned up a bit, but standard valves and valve springs are retained. The valves operate via stock camshafts, although cam timing is altered. The cylinder heads are milled to increase compression, but that’s about it for internal engine changes.

Most of the bike's 20-horsepower increase over a showroom-stock GSX-R l 100 can be attributed to its quartet of carburetors—37mm or 39mm racing Keihins-and its suitably loud 4-into-l exhaust plumbing.

Actually, the Lockhart l 100’s wheels and brakes probably have as much to do with the bike’s record as do its chassis or engine tweaks. The wide, Mitchell aluminum wheels—3.5 inches, front, 5.5, rear—permit the use of sticky, GP-quality rubber. And the Performance Machine rotors and calipers, along with SBS pads, mean that Quarterly and Shorts can count on tire-howling, fade-free braking from flag to flag.

Perry sums up his approach to buiding championshipwinning racebikes with a variation of the If-it-ain’t-brokedon’t-fix-it axiom. “The bike was fast enough and it didn’t wobble, so we left it alone,” he says.

* * *

After two laps to warm the tires, I take Larry Shorts’ advice and try to keep the engine spinning above 7000 rpm, where it begins to pull with authority. And instead of short-shifting, I snuggle the tach needle right against redline. “The harder you ride it, the better it’ll feel,” Shorts had said. As foreign as it seems to ride the hulking GSX-R as if it were a pipey little 600, the advice works wonders. I’m more at home on the bike now, charging the corners, turning times about five seconds per lap slower than a competitive endurance-race pace.

Still, I'm always aware of the effort and concentration needed to keep the Suzuki out of the dirt. Ride it hard, as it was built to be ridden, and Willow Springs becomes a norest proposition; even on the long front straightaway, the GSX-R is alive with acceleration. Tomorrow morning I'll wake up with sore shoulders and burning thighs.

But before I leave the track. I’m already working on a newfound respect for the basic GSX-R design. The Lockhart bike is the fastest, most reliable endurance racer in the country, yet it isn’t very far removed from the machines sitting in your local Suzuki dealership. Stripped of its numberplates and decals, and hushed up with a baffled exhaust pipe, this bike could almost go unnoticed by all but the most zealous inspector down at your local Department of Motor Vehicles.

At one point during Cycle Worlds day with the Team Lockhart Suzuki, Formula USA Champion Scott Gray took a few laps on the bike, came in and all but declared the thing a Peterbilt. And while it’s true that compared to Gray’s tight-waisted hyper-GSX-R, the Lockhart bike is a bit truckish, Phillips, Perry, Quarterly and Shorts can take some solace in this: If their GSX-R is a truck, it’s the fastest, most successful truck in all of motorcycling. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsBad Raps And Bad Reps

FEBRUARY 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsRaised Standards

FEBRUARY 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupNew Allies In the Atv Wars

FEBRUARY 1988 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

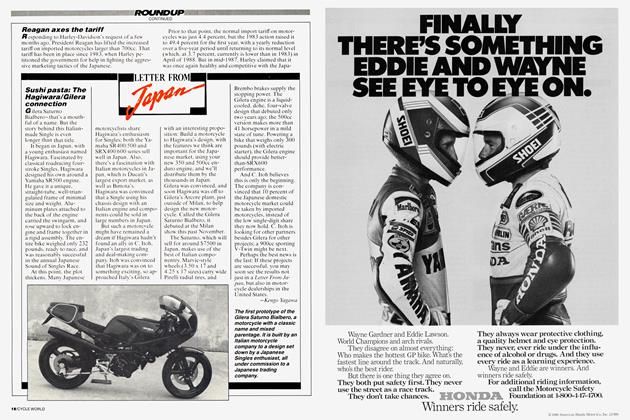

RoundupLetter From Japan

FEBRUARY 1988 By Kengo Yagawa -

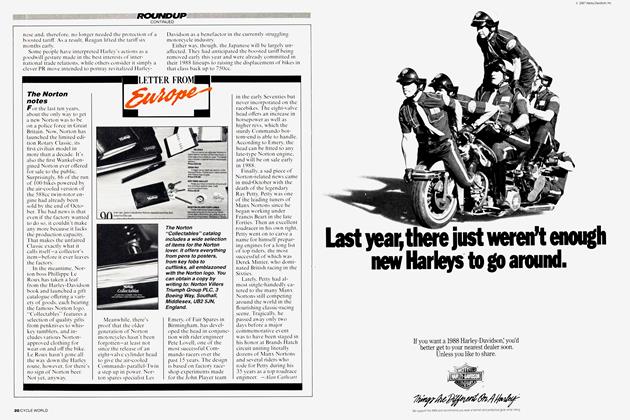

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

FEBRUARY 1988 By Alan Cathcart