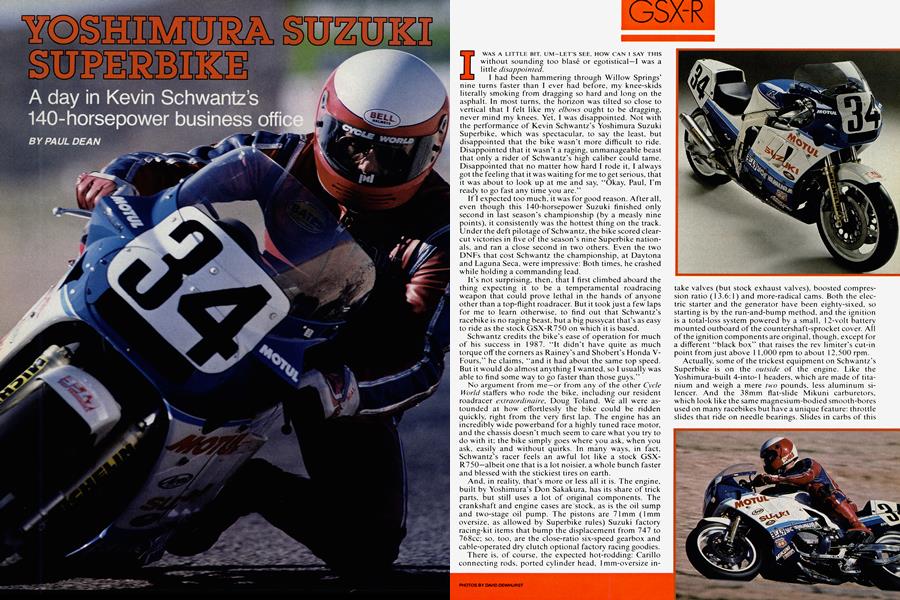

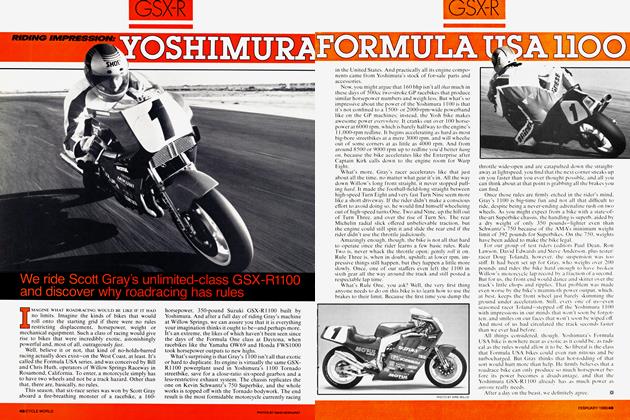

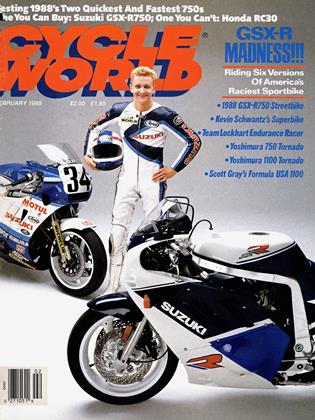

YOSHIMURA SUZUKI SUPERBIKE

A day in Kevin Schwantz's 140-horsepower business office

PAUL DEAN

GSX-R

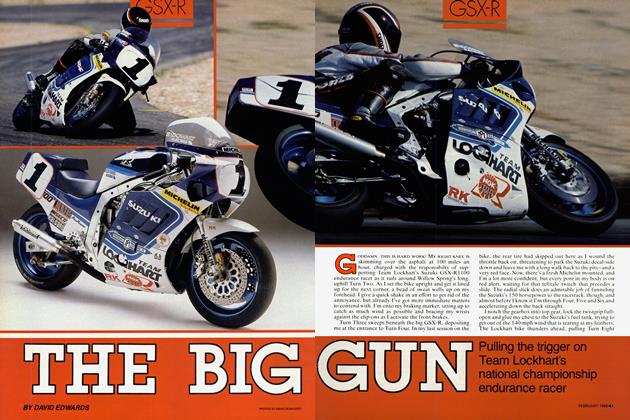

I WAS A LITTLE BIT. UM-LET'S SEE, HOW CAN I SAY THIS without sounding too blasé or egotistical—I was a little disappointed. I had been hammering through Willow Springs’ nine turns faster than I ever had before, my knee-skids literally smoking from dragging so hard and long on the asphalt. In most turns, the horizon was tilted so close to vertical that I felt like my elbows ought to be dragging, never mind my knees. Yet, I was disappointed. Not with the performance of Kevin Schwantz’s Yoshimura Suzuki Superbike, which was spectacular, to say the least, but disappointed that the bike wasn’t more difficult to ride. Disappointed that it wasn’t a raging, unmanageable beast that only a rider of Schwantz’s high caliber could tame. Disappointed that no matter how hard I rode it, I always got the feeling that it was waiting for me to get serious, that it was about to look up at me and say, “Okay, Paul, I’m ready to go fast any time you are.”-

If I expected too much, it was for good reason. After all, even though this 140-horsepower Suzuki finished only second in last season’s championship (by a measly nine points), it consistently was the hottest thing on the track. Under the deft pilotage of Schwantz, the bike scored clearcut victories in five of the season’s nine Superbike nationals, and ran a close second in two others. Even the two DNFs that cost Schwantz the championship, at Daytona and Laguna Seca, were impressive: Both times, he crashed while holding a commanding lead.

It’s not surprising, then, that I first climbed aboard the thing expecting it to be a temperamental roadracing weapon that could prove lethal in the hands of anyone other than a top-flight roadracer. But it took just a few laps for me to learn otherwise, to find out that Schwantz’s racebike is no raging beast, but a big pussycat that’s as easy to ride as the stock GSX-R750 on which it is based.

Schwantz credits the bike’s ease of operation for much of his success in 1987. “It didn’t have quite as much torque off the corners as Rainey’s and Shobert’s Honda VFours,” he claims, “and it had about the same top speed. But it would do almost anything I wanted, so I usually was able to find some way to go faster than those guys.”

No argument from me—or from any of the other Cycle World staffers who rode the bike, including our resident roadracer extraordinaire, Doug Toland. We all were astounded at how effortlessly the bike could be ridden quickly, right from the very first lap. The engine has an incredibly wide powerband for a highly tuned race motor, and the chassis doesn’t much seem to care what you try to do with it; the bike simply goes where you ask, when you ask, easily and without quirks. In many ways, in fact, Schwantz’s racer feels an awful lot like a stock GSXR750—albeit one that is a lot noisier, a whole bunch faster and blessed with the stickiest tires on earth.

And, in reality, that’s more or less all it is. The engine, built by Yoshimura’s Don Sakakura, has its share of trick parts, but still uses a lot of original components. The crankshaft and engine cases are stock, as is the oil sump and two-stage oil pump. The pistons are 71mm (1mm oversize, as allowed by Superbike rules) Suzuki factory racing-kit items that bump the displacement from 747 to 768cc; so, too, are the close-ratio six-speed gearbox and cable-operated dry clutch optional factory racing goodies.

There is, of course, the expected hot-rodding; Carillo connecting rods, ported cylinder head, lmm-oversize intake valves (but stock exhaust valves), boosted compression ratio ( 1 3.6:1 ) and more-radical cams. Both the electric starter and the generator have been eighty-sixed, so starting is by the run-and-bump method, and the ignition is a total-loss system powered by a small, 12-volt battery mounted outboard of the countershaft-sprocket cover. All of the ignition components are original, though, except for a different “black box” that raises the rev limiter’s cut-in point from just above 1 1,000 rpm to about 12,500 rpm.

Actually, some of the trickest equipment on Schwantz's Superbike is on the outside of the engine. Like the Yoshimura-built 4-into-l headers, which are made of titanium and weigh a mere two pounds, less aluminum silencer. And the 38mm flat-slide Mikuni carburetors, which look like the same magnesium-bodied smooth-bores used on many racebikes but have a unique feature: throttle slides that ride on needle bearings. Slides in carbs of this type tend to stick open, and the bearings eliminate that tendency without the need for super-stiff return springs.

Kevin Schwantz on his Suzuki’s ease of operation: “It didn’t have quite as much torque off the corners as Rainey’s and Shobert’s Hondas, but I could ride it just about anywhere on the track and take weird lines, so I usually was able to go faster than those guys; it also confused anyone who tried to follow me!’

It’s little things like that which help make Schwantz’s racer so undemanding to ride. Ditto for the carburation, which is crisp at all engine speeds, even at casual, streetriding rpm. Obviously, the engine doesn't make a million horsepower down there, but considering it’s a class-beating race motor, it performs respectably when it's “off the cams.” The engine starts getting noticeably spunkier around 7500 or 8000 rpm. and by the time it reaches 9000 there’s serious horsepower on the job. From there, all the way up to and slightly beyond 12,000 rpm. the engine is all business, whisking out of corners and down the straights with deceptive quickness.

Still, though Schwantz's bike is impressively fast—140 horsepower isn’t chopped liver—its engine performance isn’t what I had expected. I had thought that in its powerband, it would be like a semi-controlled explosion, lunging forward with such violence that I'd be left hanging on bv my fingertips, my feet straight out behind me like a cartoon character as the bike rampaged down the straights.

But it was nothing of the sort. Instead, it was -s^e^Ar-fast, never cutting loose with warp-speed acceleration, but somehow gathering an awful lot of speed in a very short time. Consequently, I’d find myself roaring into the turns sooner—and faster—than I had anticipated. No wonder I quickly came to love the dual Nissin twin-piston front brakes, which always had enough easily regulated whoapower to lift the rear wheel off the ground at triple-digit speeds—er, involuntarily, of course.

At first, I was reluctant to admit that I thought the engine’s absence of malice was wonderful. The power delivery was so smooth and predictable that the rear wheel didn’t seem likely to break loose if I happened to wick the throttle open a bit too early coming out of a turn. But Schwantz agreed whole-heartedly, praising the engine for its unfailing tractability, even when circumstances during the season had prompted him to ride extremely aggressively. “I always could slide the rear tire when I had to,” he said, “without having to worry about losing the rear end completely if I got on the gas too soon.”

Still, Schwantz is quick to point out that the Suzuki’s predictability was a by-product of its handling more than of its engine performance. “I could drive the thing around just about anywhere on the track I wanted,” he said, “and take weird lines. That made it easier for me to pass lapped riders. It also confused the hell out of anyone who tried to follow me.”

Although I didn’t have Wayne Rainey and two dozen other Superbike hotshoes chasing me, my time on the bike at Willow taught me what Schwantz meant by that remark. It wasn't long before I was able to toss the 392-pound 750 around like something half its size and weight; and I, too, was able to take some really oddball lines through turns or easily change lines once I was in them. I also could pound the bike into a corner more aggressively than anything I had ever ridden, all without protest from the chassis or the tires. Only toward the end of the day was I able to summon enough courage to induce a trace of rear-wheel drift in certain corners by whacking the throttle w ide-open right at or before the apex.

According to Schwantz, the Michelin radial rear slick plays the most significant role in the bike’s magical handling. “Those tires are amazing,” he says with a big smile, recalling some of his finer moments of 1987. “I had so much confidence in the rear tire that I’d try just about anything if I had to. I crashed a lot last year, but never because of the rear tire. The biggest reason why I did so much better last year than in 1986 was that our switch to Miehelins allowed us to run those rear radiais.”

Fair enough. But without the strong, rigid chassis supplied to Yoshimura by Suzuki, the 17-inch radiais wouldn’t have been able to perform so admirably. Of particular interest is the frame, which is, in effect, two frames. The ’86-’87 GSX-R750 frames flexed excessively under the stress of all-out racing, so Suzuki cut key sections out of another GSX-R750 frame and welded them over top of the Superbike’s frame. This, in conjunction with a massively reinforced steering head and swingarm, yielded a strong, rigid structure that complies with the AMA’s requirement that a Superbike use a stock-based frame.

Suzuki also equipped the bike with an ultra-trick Showa racing suspension. The front fork is a sturdy assembly that uses handmade triple-clamps, hefty 43mm tubes, external spring-preload adjusters, and independently adjustable highand low-speed compression and rebound damping. The rear shock is a bit less all-adjustable, having provisions only for preload, for compression and rebound damping, and for ride height.

Because I'm about 50 pounds heavier than Schwantz, Sakakura spent a lot of time during the day twirling all those adjustments. And by the time I headed out onto the track for my final stint, the bike was handling magnificently, having gained added stability and predictability with each and every adjustment.

I decided, then, to hang it all out during that last session, to see if I could get even close to competitive Superbike lap times. I kept running deeper and deeper into the corners, waiting so long before turning that I’d have to bank the Suzuki over with abruptness that would almost take my breath away. And as I exited the turns, I’d dial the throttle open a bit sooner than I had the lap before, all the while reminding myself that everything w'as going to be okay, that Kevin Schwantz had ridden this same bike a lot faster and harder than I was riding it, and it had never done anything terrible to him.

It seemed to be working. As I kept going faster and faster, the Suzuki did nothing to indicate that it was getting close to its limits.

That’s when I decided to call it quits. Because although I had not yet used all of the Suzuki’s potential, I definitely had used all of mine, and things were starting to happen too fast (although as I later learned, I still was four or five seconds off a competitive pace). And the last thing I wanted to do was turn one of the country’s finest Superbikes into $30,000 worth of junkyard fodder. So I eased off'the throttle and leisurely cruised back to the pits for the last time. My day had been pure fun up to that point, and I didn't want to let a little ego problem become a major medical problem.

Later, as I helped Sakakura push the bike back into the van, he asked, “Well, what did you think of it?”

I pondered that question for a moment, then replied, “I really liked it. I'm just sorry that I wasn’t able to go as fast as it was able to go.”

“Don't feel too bad,” he said with a wry grin. “After following Kevin all year, every Superbike rider in the country probably feels the same way.”

Touché, Don. touché.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsBad Raps And Bad Reps

FEBRUARY 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsRaised Standards

FEBRUARY 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupNew Allies In the Atv Wars

FEBRUARY 1988 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

FEBRUARY 1988 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

FEBRUARY 1988 By Alan Cathcart