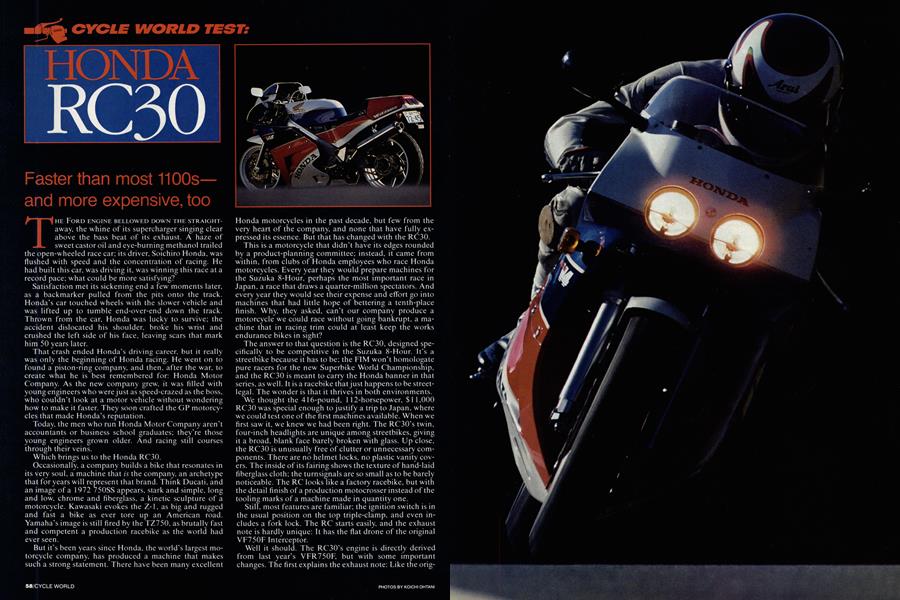

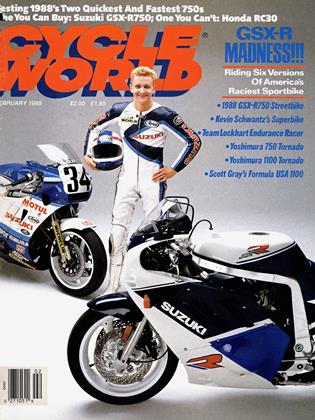

HONDA RC30

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Faster than most 1100s— and more expensive, too

THE FORD ENGINE BELLOWED DOWN THE STRAIGHTaway, the whine of its supercharger singing clear above the bass beat of its exhaust. A haze of sweet castor oil and eye-burning methanol trailed the open-wheeled race car; its driver, Soichiro Honda, was flushed with speed and the concentration of racing. He had built this car, was driving it, was winning this race at a record pace; what could be more satisfying?

Satisfaction met its sickening end a few moments later, as a backmarker pulled from the pits onto the track. Honda’s car touched wheels with the slower vehicle and was lifted up to tumble end-over-end down the track. Thrown from the car, Honda was lucky to survive; the accident dislocated his shoulder, broke his wrist and crushed the left side of his face, leaving scars that mark him 50 years later.

That crash ended Honda’s driving career, but it really was only the beginning of Honda racing. He went on to found a piston-ring company, and then, after the war, to create what he is best remembered for: Honda Motor Company. As the new company grew, it was filled with young engineers who were just as speed-crazed as the boss, who couldn’t look at a motor vehicle without wondering how to make it faster. They soon crafted the GP motorcycles that made Honda’s reputation.

Today, the men who run Honda Motor Company aren’t accountants or business school graduates; they’re those young engineers grown older. And racing still courses through their veins.

Which brings us to the Honda RC30.

Occasionally, a company builds a bike that resonates in its very soul, a machine that is the company, an archetype that for years will represent that brand. Think Ducati, and an image of a 1972 750SS appears, stark and simple, long and low, chrome and fiberglass, a kinetic sculpture of a motorcycle. Kawasaki evokes the Z-l, as big and rugged and fast a bike as ever tore up an American road. Yamaha’s image is still fired by the TZ750, as brutally fast and competent a production racebike as the world had ever seen.

But it's been years since Honda, the world’s largest motorcycle company, has produced a machine that makes such a strong statement. There have been many excellent Honda motorcycles in the past decade, but few from the very heart of the company, and none that have fully expressed its essence. But that has changed with the RC30.

This is a motorcycle that didn’t have its edges rounded by a product-planning committee; instead, it came from within, from clubs of Honda employees who race Honda motorcycles. Every year they would prepare machines for the Suzuka 8-Hour, perhaps the most important race in Japan, a race that draws a quarter-million spectators. And every year they would see their expense and effort go into machines that had little hope of bettering a tenth-place finish. Why, they asked, can’t our company produce a motorcycle we could race without going bankrupt, a machine that in racing trim could at least keep the works endurance bikes in sight?

The answer to that question is the RC30, designed specifically to be competitive in the Suzuka 8-Hour. It’s a streetbike because it has to be; the FIM won’t homologate pure racers for the new Superbike World Championship, and the RC30 is meant to carry the Honda banner in that series, as well. It is a racebike that just happens to be streetlegal. The wonder is that it thrives in both environments.

We thought the 416-pound, l 12-horsepower, $1 1,000 RC30 was special enough to justify a trip to Japan, where we could test one of the first machines available. When we first saw it, we knew we had been right. The RC30’s twin, four-inch headlights are unique among streetbikes, giving it a broad, blank face barely broken with glass. Up close, the RC30 is unusually free of clutter or unnecessary components. There are no helmet locks, no plastic vanity covers. The inside of its fairing shows the texture of hand-laid fiberglass cloth; the turnsignals are so small as to be barely noticeable. The RC looks like a factory racebike, but with the detail finish of a production motocrosser instead of the tooling marks of a machine made in quantity one.

Still, most features are familiar; the ignition switch is in the usual position on the top triple-clamp, and even includes a fork lock. The RC starts easily, and the exhaust note is hardly unique: It has the flat drone of the original VF750F Interceptor.

Well it should. The RC30’s engine is directly derived from last year’s VFR750F, but with some important changes. The first explains the exhaust note: Like the original VF750F, the RC30 has a 360-degree crank. The pistons of each front and rear cylinder bank rise and fall together, as if the engine were two British parallel-Twins mounted on common cases. The original Interceptor and the RC30 use this design because it allows the most efficient exhaust tuning; the VFR750F’s 180-degree crank evidentally sacrificed some powerband for a more-even firing order and a sexier exhaust note.

So, the RC30 has a flat, droning exhaust, one that sounds as if the engine is never working very hard. There’s more of a rasp to it than with the original Interceptor; if you've ever heard an early Honda V-Four Superbike, that’s the sound, though muffled and muted to present standards of civility.

Another change the RC30 engine received helps explain the machine's solid-gold price tag: titanium connecting rods. Titanium, with the best strength-to-weight ratio among metals, is the premium choice for connecting rods—that is, if cost is no object. These lightweight rods reduce the loads on the big-end bearings, and allow them easily to live even at the RC30's 12,500-rpm redline. They also ensure that Honda's racing teams can use rods of this light metal; some racing rules require that con-rod material be the same as original production. Finally, by reducing reciprocating weight, the rods help reduce vibration and make this the smoothest-running of the solidly mounted Honda V-Fours.

But perhaps the most important change in the engine is its cylinder-head redesign (illustration, pg. 62). As with every engine Honda designs for racing purposes, the RC30 has new heads with twin camshafts that actuate their valves through bucket tappets. Compared to the VFR750F's rocker-arm design, the new valve train has less reciprocating weight, less friction and greater reliability, even with a 12,500-rpm redline. The closer spacing of the camshafts also makes the new heads much more compact, and the bucket tapppets leave room for straighten betterflowing ports.

These heads are really nothing but mainstream Honda racing designs. And the RC30 engine, in street trim, works much like the engine in one of Honda’s endurance-racing V-Fours. The 1 12-horsepower motor starts and idles like any tame street engine, and pulls adequately to about 6000 rpm. Then, from 6500 rpm to redline, the RC30 pulls hard and steadily, with one of the smoothest powerbands found on any motorcycle. Crisp carburation turns the throttle into a rheostat: If you want more power you just dial it on, and you have it, smoothly and progressively, without any bangs or lurches in the driveline.

Between the flat torque curve and the flat exhaust, it’s difficult for a rider to gauge the RC30’s performance. Its close-ratio, roadrace-style gearbox even removes quartermile acceleration as a standard; like Yamaha’s FZR750R, the RC30 carries a 80-mph first gear that won’t launch the bike quickly from a standing start. The result is high-1 1second quarters from a machine with a power-to-weight ratio that should put it into the tens. But one measure does tell: At the banked oval test track at the Japanese Automobile Research Institute (JARI), we clocked our RC30 at 155 mph, the third-fastest production motorcycle we’ve ever measured, and the fastest 750 by far. And the JARI test track wasn’t ideal for a top-speed test; we’re certain the RC30 would have gone at least two or three mph faster if tested at our usual U.S. site. It is the most powerful 750 we’ve ever ridden.

It’s also one of the best-handling. That’s not surprising, as its chassis is a close replica of the one used on recent Honda endurance racers. Massive five-sided beams reach around the engine to tie swingarm pivot rigidly to steering head; the rigid engine-mounting further braces the frame. A single-sided swingarm (rumored to be built under license from ELF, whose endurance racers used the same design years earlier) allows quick rear-wheel changes. The wheels are spaced only 55.5 inches apart, and are themselves exactly the right size for racing; the front a 3-inchwide 1 7-incher fitted with a 1 20/70 bias-ply tire, the rear a Superbike-spec 5.5-inch-wide 18 wearing a 170/60 radial. Buy this bike to go racing, and there’s no need to hunt down $500 Italian racing wheels in order to run radial slicks.

Nor is there any reason to change the suspension. The Showa cartridge fork and de Carbon-style shock are further racing replicas, and give the RC30 the best suspension on a street-going motorcycle. The fork and shock are multi-adjustable, with easily tunable compression and rebound damping.

But even at the nominal settings, the RC30’s suspension is a revelation. The fork is always compliant, and while still maintaining precise wheel control, simply rounds the corners of square-edged expansion joints that on any other bike would send a sharp impact to the bars. The rear suspension works equally well, in continual motion to smooth any road surface. The springing is by no means soft, but the precision damping keeps the ride controlled and comfortable at all times; the RC30 simply raises the standards for suspension several notches.

Between the suspension, the chassis and the engine, the RC30 offers a complete performance package. Steering isn’t lightning-quick, but the bike turns into a corner readily, with complete stability. Once leaned over, it offers an amazing combination of stability and sensitivity. Small steering inputs or rider weight-shifts can change the RC30’s line, but the steering feels so positive that this is simply a benefit, allowing a rider to steer the bike wherever he may want to go; this machine is as far from being twitchy as a motorcycle can be. The suspension simply absorbs most road irregularities, though the biggest bumps in corners do tend to bounce the RC30 upright.

The fairly narrow-section front tire, however, minimizes the effect of braking on steering; you can trail-brake into a corner without much change of steering effort. And the engine’s 1 12 horsepower doesn’t get the rider in trouble, coming on so smoothly that it never surprises. The endurance-racer heritage shows: The RC30 goes very fast without tiring its rider with unnecessary twitches or danger signals.

Only in its seating position does the RC30’s racing heritage compromise its street usability. The footpegs are higher and further aft than typical for most sportbikes (though the seat-to-footpeg distance is roomier than the FZR750R’s), and the handlebars are genuine low clipons. The rider sits far to the front of the machine, with a short gas tank, so it’s no stretch to the bars, although normal street riding does put considerable weight on a rider’s arms.

All in all, the RC30 is probably no more uncomfortable than a GSX-R or FZR (even its thinly padded seat is wide enough to support its rider’s weight evenly and prevent painful pressure points), but make no mistake: This is a machine designed to be ridden on twisty roads or racetracks, and it won’t be comfortable on straight highways or around town.

In the end, though, the most important facts about the RC30 for Americans may be its price and its availability. An initial production run of 1000 RC30s has begun in Japan; these motorcycles have already all been spoken for at 1,480,000 Yen, or $11,000 at current exchange rates. That’s either dreadfully expensive (for a streetbike), or a real bargain for a machine that might only require another $5000 of modifications to be turned into a reasonably competitive Superbike or endurance racer. It all depends on your point of view—and the depth of your bank account.

Of more concern is that American Honda, in mid-September, cancelled all plans to bring the RC30 to the United States. This was in reaction to the proposed Danforth legislation to ban high-performance motorcycles; American Honda didn’t want to throw RC30 gasoline on that particular fire. Still, the decision came as a shock to both Honda in Japan and the Honda racing department in the U.S. Both groups had planned on the RC30 being sold in the U.S., and on it being raced in Superbike competition here.

Even now, Japanese Honda officials seem perplexed that the RC30 will not be sold in the U.S. “It’s American Honda’s problem,” they say while shaking their heads in disbelief. The bike is very much Honda’s showpiece, and Japan would very much like to see it sold in Honda’s largest export market.

With the Danforth bill now simply a bad memory, perhaps American Honda’s management will reconsider and offer the RC30 in the U.S. If they do, you may have the opportunity to buy a machine that earns many superlatives: the lightest Japanese-built 750, the most expensive, the fastest, the best suspended, among others. But perhaps most important, the RC30 is a machine straight from Honda’s soul.

HONDA

VFR75OR RC3O

$10,890

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsBad Raps And Bad Reps

FEBRUARY 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsRaised Standards

FEBRUARY 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupNew Allies In the Atv Wars

FEBRUARY 1988 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

FEBRUARY 1988 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

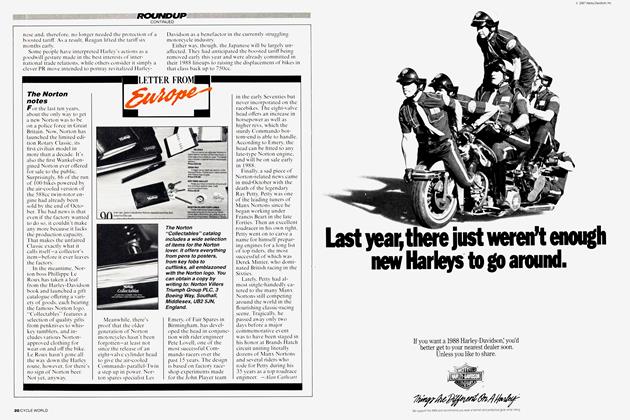

RoundupLetter From Europe

FEBRUARY 1988 By Alan Cathcart