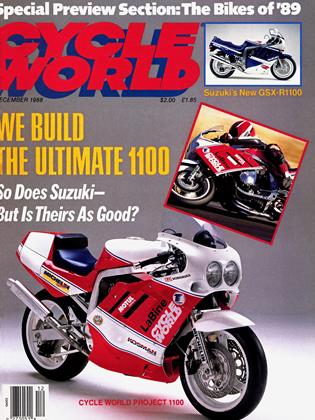

The Peoria TT

RACE WATCH

Before Supercross was born, dirt-trackers flew high. At Peoria, they still do.

STEVE ANDERSON

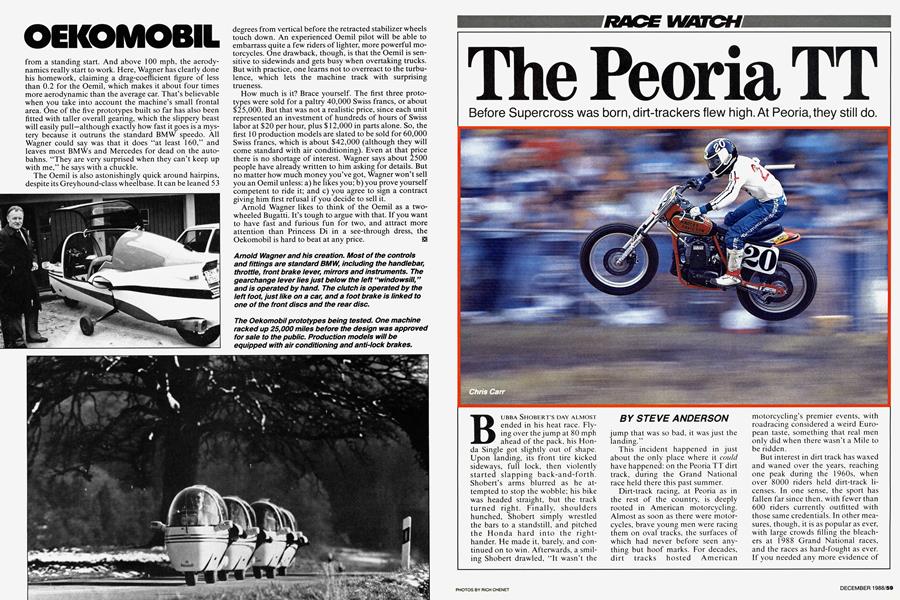

BUBBA SHOBERT'S DAY ALMOST ended in his heat race. Flying over the jump at 80 mph ahead of the pack, his Honda Single got slightly out of shape. Upon landing, its front tire kicked sideways, full lock, then violently started slapping back-and-forth. Shobert's arms blurred as he at tempted to stop the wobble; his bike was headed straight, but the track turned right. Finally, shoulders hunched, Shobert simply wrestled the bars to a standstill, and pitched the Honda hard into the right hander. He made it, barely, and con tinued on to win. Afterwards, a smil ing Shobert drawled, "It wasn't the

jump that was so bad, it was just the landing.”

This incident happened in just about the only place where it could have happened: on the Peoria TT dirt track, during the Grand National race held there this past summer.

Dirt-track racing, at Peoria as in the rest of the country, is deeply rooted in American motorcycling. Almost as soon as there were motorcycles, brave young men were racing them on oval tracks, the surfaces of which had never before seen anything but hoof marks. For decades, dirt tracks hosted American

motorcycling’s premier events, with roadracing considered a weird European taste, something that real men only did when there wasn’t a Mile to be ridden.

But interest in dirt track has waxed and waned over the years, reaching one peak during the 1960s, when over 8000 riders held dirt-track licenses. In one sense, the sport has fallen far since then, with fewer than 600 riders currently outfitted with those same credentials. In other measures, though, it is as popular as ever, with large crowds filling the bleachers at 1988 Grand National races, and the races as hard-fought as ever. If you needed any more evidence of dirt track’s enduring appeal, you had only to see this year’s Peoria TT.

TT racing is the forgotten stepchild of dirt track, once one of its more popular forms, now one of the least raced. A TT track, by definition, is simply a dirt track with at least one right-hand turn and one jump. Some are as elaborate as any roadrace course, with complex twists and two or three jumps per lap, while others

are merely a half-mile oval with a right-hand kink and a jump added.

Peoria’s TT track is closer to the latter, about half-mile-sized, basically oval, with a fast jump overa hill on the back straight, followed by a slightly downhill right-hand kink. The racers describe it much as they would a half-mile, with the first 1 80degree sweeping left-hander made up of “Turns One and Two,” and the

other 180-degree left “Turns Three and Four.” The right-hand corner isn’t honored with a number; it’s simply “the right” or “the kink,” the obstacle you’re faced with immediately after landing from the jump.

But in the Grand National series, Peoria is a very special place. It’s the only TT left in the dirt-track title chase, and it’s a Camel Pro race as well as a Grand National. The latter is important because in the last few years, the structure of American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) racing has become complicated. There are dirt-track Grand Nationals for 750cc Twins, paying points that can lead to the dirt-track championship and the right to wear the dirt-track Number One plate (black number on white background). Recently, the AMA has added a separate series of dirttrack races for 600cc Singles, with a 600cc national title; except for TT races, the 600s are no longer allowed to run with the 750s. Alongside the dirt-track events is the Superbike roadrace championship, resulting in a roadrace Number One plate.

There’s also the Camel Pro championship. R.J. Reynolds, the makers of Camel cigarettes, sponsors only AMA National roadraces and a select group of dirt-track events (nine in 1988). These constitute the Camel Pro Series, and the rider accumulating the most points in these events can fit his machine with the yellowand-blue Camel Number One plate the next season, essentially the crown of the overall AMA national champion.

Peoria is the one race that wraps most of those strands together. It’s a Grand National dirt track, a Camel Pro Race, and the one National race of the year where the 750s and 600s can run together.

Besides that, it’s Peoria, special in its own right. The first Peoria TT ran on the current track in 1946, making this one of the oldest Nationals on the dirt-track circuit. Then, like now, the setting could hardly be better. The track nestles in a small, grassy valley, surrounded by tree-covered hills where spectators can sit in the shade (much appreciated during a hot and humid Midwestern summer day). The 80 acres of trees and grass surrounding the track are owned by the Peoria Motorcycle Club, a 55year-old, AMA-chartered club that holds the TT every year as a fundraiser.

With a club as the race promoter, and volunteer club members manning the corners, working the the ticket booths and directing traffic, the Peoria TT has a family feel unlike any other AMA National. You can find cornerworkers like Wayne Ockerby, a club member who has worked every Peoria TT since 1946. Ockerby points out that, “We’re not out to gouge the public; we just want to run the club for a year.” The $ 10 price on advance-sale tickets is reasonable, indeed, especially since children under 12 are admitted free; and the crowd at Peoria is always large, with 14,000 estimated at this year’s race. The Peoria Motorcycle Club uses the money they do make to help sponsor its Friday night fish fries (for club members only), donates some to charity, and uses the rest to finance improvements to its property.

Of course, for some of the racers, this year’s Peoria TT was important for other reasons. Camel Pro and dirt-track champion Bubba Shobert was looking to repeat at least his Camel title, worth $100,000 from R.J. Reynolds, in addition to a large cash bonus from Honda. But while Shobert, gathering points with factory Hondas in both Superbike and

dirt-track events, was close to locking up the Camel Series, the dirt-track black-and-white Number One plate was still up for grabs. Harley-Davidson factory rider Scotty Parker held a

slight lead in dirt-track points going into Peoria (144 to 131), and noted, “All season it’s been close; I’ve been within eight points until Bubba didn’t run one of the races. I jumped up on that and got about 16 points on him. He whittled that lead down to where it was pretty close, and now it’s back to racing.”

Parker’s Harley teammate, Chris Carr, running a close third with 124 points, planned to use Peoria as the springboard for a late-season charge; “This is the most important race on the schedule; it’s the turning point of the season,” said a hopeful Carr.

Many privateers had hopes, as well. Steve Morehead, having an exceptional year on private Harleys, was just behind Carr in dirt-track points, and with wins in some earlyseason races, was third in Camel points. A 3 3-year-old, oval-track specialist who normally stays away from TTs, Morehead found himself at Peoria for the first time in five years.

“With the Camel points we’re so darn close, I had to come here and ride this,” he explained.

Doug Chandler, who is trying to do

both the Camel Pro roadrace and dirt-track races on a privateer’s budget, wanted both the points and the purse; he was in good position to do well in the final Camel standings and cut himself a largish piece of R.J. Reynolds’ end-of-the-season payout. And then there were top riders like Ricky Graham, Dan Ingram and Ronnie Jones, who always run strongly, and who would have liked nothing more than to upset their factory-financed colleagues.

At Peoria, an upset was definitely possible, if not likely. While Shobert, the previous year’s winner, was one of the favorites, he was far from a shoo-in, particularly because of Chris Carr. Carr scored his first Expert National win at Peoria in 1986, and lost to Shobert last year in the last few laps, fading back to second place toward the end of a hot and fatiguing race. This year, Carr had stepped up his training program, and, once again, equipment was playing into his hands.

That’s because absolutely no one elected to try racing a 320-pound, 90horsepower 750 Twin against a 230pound, 65-horsepower 600 Single on even a wide-open TT track like Peoria. The lighter Singles (Rotax and Honda-powered) were judged to be at least as quick as a Twin for a single lap; and with their 90-pound weight advantage, they were more likely to maintain that speed for 25 laps on a physically demanding track on a hot day. And for racing the 600s, the 21year-old Carr was on the right side of the dirt-track generation gap.

The older riders (and in dirt track, that includes anyone much older than Carr) have raced 750 Twins ever since they held Junior rank, and they largely don’t like the lightweight Singles. With at least slight disparagement, they refer to the Singles as the “little bikes.” But Carr has been riding Wood-Rotax Singles almost since the beginning of his professional career; and he was as responsible as any rider for chasing most of the 750 Twins out of the Junior ranks and away from the Peoria TT by regularly beating them on one of those “little bikes.” So, it’s no surprise that Carr truly likes the Singles, and has been one of the few 750-class front-runners regularly competing in 600cc dirt-track races. In fact, by Peoria, he was close to clinching the 600cc dirttrack title.

Carr’s competitors admitted that his experience gave him an edge. Steve Morehead, a 750 proponent if there ever was one, said, “ My biggest downfall is that I don’t ride the 600s except maybe a half-dozen times a year. It’s hard to get sharp. It’s more of an advantage for a lot of the younger kids. They’ve grown up racing these things, like Carr. He’s such a natural on his it’s just unbelievable. He rides the shit out of it. It looks like that motorcycle is molded around him.” Even Bill Werner, Scott Parker’s star tuner, conceded that, “Chris has the advantage here. He’s been riding the little bikes all year. He grew up on the little bikes. Scotty likes the 750s better. This is Chris’s part of the season, and we just have to do as good as we can and get points.”

Time trials confirmed those suspicions, with Carr setting a new lap record for the Peoria course. But Parker was close behind, proving that riding a Single only once a year wasn’t much of a disadvantage. Shobert held the fourth-fastest qualifying time, one-hundredth of a second behind Ronnie Jones. But by winning the pole, Carr put himself into the first heat race, not the most desirable position. Explained Carr, “The track changes a lot from the first heat to the final. Ideally, you’d like to be in the fourth heat. In the first heat, the track can be perfect; you can ride anyplace, not a hint of a groove. By the final, it can groove up and be just a few feet wide. You want to set up the suspension and gearing so you get the best drive, and that depends on track conditions.”

Not surprisingly, Carr ran away with the first heat, winning by almost the length of the front straight. Neither did the rest of the heat races hold any surprises. Parker won the second, and former National Champion Ricky Graham stylishly beat Ronnie Jones in the third. The fourth heat belonged to Shobert, even if his early tank-slapping jump landing gave him a little extra adrenaline rush.

After the semi-final events determined the remainder of the field, the six fastest qualifiers lined up for the Camel Dash, a five-lap, cigarette-

company-sponsored sprint with a $10,000 first prize. While Carr bobbled the start (spinning his tire and getting sideways off the line), Shobert led into Turn One. But Carr recovered to take second behind Shobert before the pack was out of Turn Two, and the chase was on. By the third lap, Carr and Shobert were pulling away from Jones and Parker, and Carr was trying to find a way around Shobert. But while he could stick a wheel in on Shobert, he couldn’t make a pass stick.

Finally, on the last lap, Carr squared off the final corner in an attempt to pass Shobert on the inside, only to fall a few feet short at the finish line. But while Shobert took the $10,000, Carr took note of the track conditions before the final, and decided that his gearing had been slightly too tall. “The day’s not over,” he warned. And later, when the field gridded for the final, Carr’s bike wore a one-tooth-larger rear spocket.

Still, the race started as a replay of the Camel Dash: Shobert led off the line, with Carr in close pursuit, Parker following. Over the jump, Carr’s bike landed much the smoothest; later, he would attribute that smoothness to the suspension development he and his tuner, Mike Camphouse, had done in the 600 Nationals, and to riding technique. At previous Peoria races, Carr was perhaps the only rider to take the jump flat-out; now he was calming himself down and not trying to play Evel Knievel. “I concentrated on keeping the length of my jump down so I could turn the bike to the left, setting it up for the right-hander. I could then be on the gas through the righthander. Rolling off just before hitting the lip of the jump allows the suspension to settle and work good.” Carr pulled up to Shobert and began looking for a way around. He found it on the fourth lap, slipping past on the straight just before Turn One, then pulling away. Meanwhile, Shobert had to contend with Parker; by the sixth lap, the Harley-sponsored rider squeezed by Shobert in Turn One. That’s where the race

stood until lap 17, when Parker bobbled, allowing Shobert back around. But by then, Carr was long-gone, on his way to setting a new 25-lap record time for the Peoria event, breaking the old record by an impressive 19 seconds and lapping the field through seventh place. Parker made a do-or-die attempt to pass Shobert on the last corner of the last lap; and while he got very out-of-shape, he had no success, instead finishing third.

So, in the end, the factory riders were all left at least relatively satisfied. Parker retained his points lead with a strong third-place finish— surely not his hope, but sufficient to carry him through Peoria to the upcoming Mile races. Shobert, with second, gained a few points on Parker, and did win the $10,000 of Camel money.

And Carr was understandably ecstatic. “I really concentrated hard on this particular event. I’ve been working my butt off all year long, and this is just one of the funnest races to run all year long. And the fans are the closest to us here than anywhere else.

I wish I had a track like this in my back yard.”

He then explained why a back-yard replica of this particular track would be useful: “Racing Peoria is almost like coming home.”

Peoria TT Results

1) Chris Carr, Harley-Davidson

2) Bubba Shobert, Honda

3) Scott Parker, Harley-Davidson

4) Ronnie Jones, Honda

5) Ricky Graham, Harley-Davidson

6) Dan Ingram, Harley-Davidson

7) Scott Pearson, Honda

8) Steve Morehead, Harley-Davidson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialAdios, Specialization

December 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeEngineers

December 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

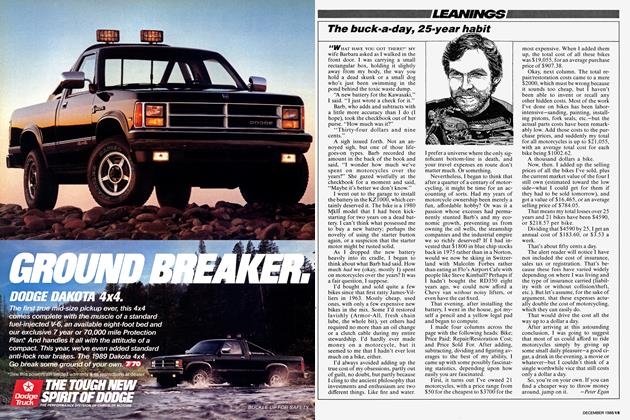

Learnings

LearningsThe Buck-A-Day, 25-Year Habit

December 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupWhither the Passenger?

December 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

December 1988 By Alan Cathcart