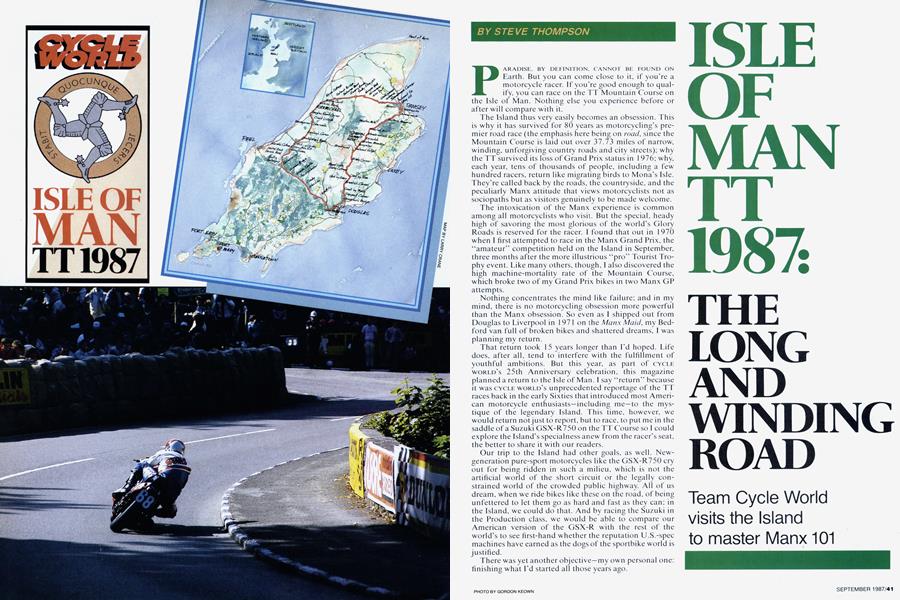

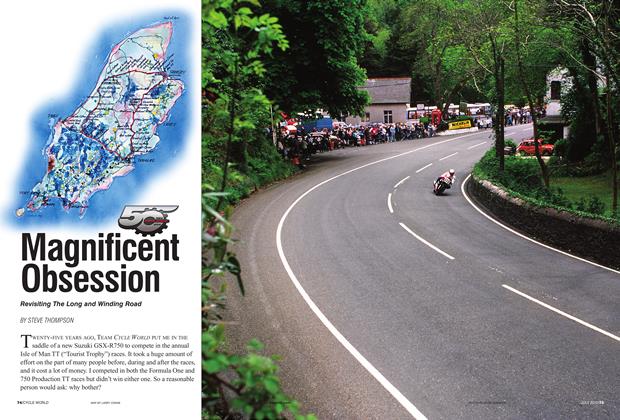

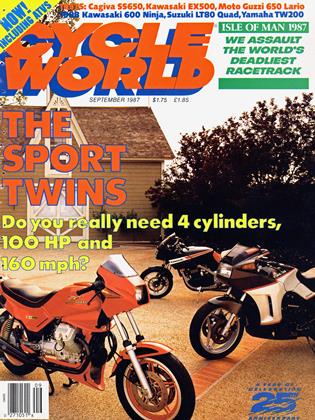

ISLE OF MAN TT 1987: THE LONG AND WINDING ROAD

Team Cycle World visits the Island to master Manx 101

STEVE THOMPSON

PARADISE. BY DEFINITION. CANNOT BE FOUND ON Earth. But you can come close to it, if you're a motorcycle racer. If you're good enough to qualify, you can race on the TT Mountain Course on the Isle of Man. Nothing else you experience before or after will compare with it.

The Island thus very easily becomes an obsession. This is why it has survived for 80 years as motorcycling’s premier road race (the emphasis here being on road, since the Mountain Course is laid out over 37.73 miles of narrow, winding, unforgiving country roads and city streets); why the TT survived its loss of Grand Prix status in 1976; why, each year, tens of thousands of people, including a few hundred racers, return like migrating birds to Mona’s Isle. They’re called back by the roads, the countryside, and the peculiarly Manx attitude that views motorcyclists not as sociopaths but as visitors genuinely to be made welcome.

The intoxication of the Manx experience is common among all motorcyclists who visit. But the special, heady high of savoring the most glorious of the world’s Glory Roads is reserved for the racer. I found that out in 1970 when I first attempted to race in the Manx Grand Prix, the “amateur” competition held on the Island in September, three months after the more illustrious “pro” Tourist Trophy event. Like many others, though, I also discovered the high machine-mortality rate of the Mountain Course, which broke two of my Grand Prix bikes in two Manx GP attempts.

Nothing concentrates the mind like failure; and in my mind, there is no motorcycling obsession more powerful than the Manx obsession. So even as I shipped out from Douglas to Liverpool in 1971 on the Manx Maid, my Bedford van full of broken bikes and shattered dreams, I was planning my return.

That return took 15 years longer than I'd hoped. Life does, after all, tend to interfere with the fulfillment of youthful ambitions. But this year, as part of CYCLE WORLD’S 25th Anniversary celebration, this magazine planned a return to the Isle of Man. I say “return” because it was CYCLE WORLD’S unprecedented reportage of the TT races back in the early Sixties that introduced most American motorcycle enthusiasts—including me—to the mystique of the legendary Island. This time, however, we would return not just to report, but to race, to put me in the saddle of a Suzuki GSX-R750 on the TT Course so I could explore the Island’s specialness anew from the racer’s seat, the better to share it with our readers.

Our trip to the Island had other goals, as well. Newgeneration pure-sport motorcycles like the GSX-R750 cry out for being ridden in such a milieu, which is not the artificial world of the short circuit or the legally constrained world of the crowded public highway. All of us dream, when we ride bikes like these on the road, of being unfettered to let them go as hard and fast as they can; in the Island, we could do that. And by racing the Suzuki in the Production class, we would be able to compare our American version of the GSX-R with the rest of the world’s to see first-hand whether the reputation U.S.-spec machines have earned as the dogs of the sportbike world is justified.

There was yet another objective—my own personal one; finishing what I’d started all those years ago.

1420 hours, Thursday, June 4th, 1987:

Standing next to the Suzuki GSX-R750, I feel another weird flash of déjà vu. The grid on the TT Course is like nothing else in the racing world; you line up in pairs behind the start-finish line, the row of racebikes sometimes stretching a hundred yards down Glencrutchery Road. You start in pairs, sent off to race or practice by a big man who steadies you at the line with a hand on your shoulder, slapping you when the timekeeper in the tower signals that it’s time to go.

Terry Shepherd snaps me out of the time warp. “Remember you’re on new tires with a full tank,” he says. I don’t need reminding, but he knows the tension, as he knows everything else about what is going on. And as team manager for CYCLE WORLD’S Isle of Man effort, he knows he must lead at all times, right up until the clock shows 1435:30 and they fire me off down Bray Hill to do my best against the other 70-odd men riding in the 750 Production TT this afternoon.

I tug the Bell M-2’s strap tighter and climb aboard the Suzuki as Richard, Terry’s son and able mechanic, dismounts, hand still on the throttle. This will be home for the next hour and 10 minutes or so, my perch for the 1 13 miles and three laps of the course. By now, more than 600 racing miles into TT ’87, the bike feels like home to me. I check the setting on the steering damper Shepherd has fitted, and let the pre-race fragments flit, willy-nilly, through my mind.

A decade and a half ago, when I sat here on my 350 Kawasaki, the fragments were tinged with the nagging fear that the course was still too big for me, too much to know, too immense a problem. But not today. Today, because of Shepherd and the Suzuki, the fragments are sharp photos of corners, straights, peel-off points, braking markers. I know that midway down Bray Hill for the first time, pulling 10,000 rpm in sixth gear, I will be breathing hard, exhaling in grunts through the vents in my Bell. But I know, too, thanks to Terry and to the deceptively docile Suzuki, that by the left-right kink at Braddan Bridge, all systems will be normal. Unless I do something stupid at Quarter Bridge with the unscuffed Michelin Hi-Sports and the throttle.

The three-minute board goes up, and the engines die around me. Here, Production races start with engines dead, to be lit off on the Go signal. As qualifier number 68 for this event, I will start a long way down the list.

Editor Paul Dean, clad in the bright orange Team cw coveralls unique to us—which make our refueling area easy to spot when I come barrelling into the crowded pits— shakes my hand and wishes me a good ride. Shepherd lin-

gers as the clock on the tower moves inexorably forward. Around me now. the other racers and their crews are mostly silent, the riders staring into the middle distance, tensing their minds and bodies for the wrenching change from being a normal biped at rest to crouching behind a fairing in command of a 160-mph racing bike flat-out on the toughest road circuit in the world.

The last seconds disappear in a flash, as they always do. Bikes begin to rocket off in 10-second intervals. We creep forward, my start time drawing ever nearer. I watch the lines the other riders use to avoid the dip and bumps at the top of Bray Hill, idly wondering if the new FZR Yamahas handle it better than the Suzuki does. And suddenly we are next.

Shepherd slips behind the pit wall. I flip down my visor, check that the ignition is on, the bike in first gear. Clutch in, I roll to the line, watching the starter with the flag. Next to me, a 750 Ninja rider does likewise. I’m suddenly aware of a thousand peering faces staring at us, from the pit wall, the grandstands, the trackside, everywhere, their attention perhaps focused more on me because I am the sole American riding in this year’s TT. Before I have a chance to file the picture, the flag comes up and starts down.

The Suzuki fires on the first spin of the starter motor and catapults me down Glencrutchery Road as I open the throttle to the stop. Tucking in. shifting at 1 1,200 rpm, I take the racing line and realize I’ve gotten the holeshot on the Kawasaki.

I seem to be all alone on the TT course. Again.

0545 hours, Friday, May 22nd, 1987:

Neither Shepherd nor I had realized we would have to be up this early every morning to complete my TT Course reindoctrination. But so jammed are the roads that this early-morning session is vital to us, since it’s the only time the circuit is clear.

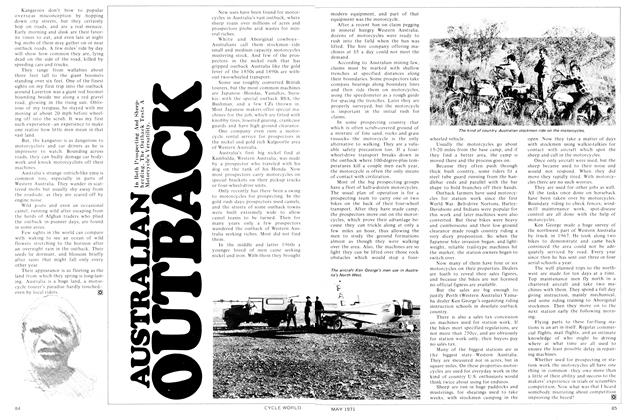

Manx 101 is what 1 call the intensive, day-long sessions in which Terry literally shepherds me along the circuit. I came to the Island thinking that my two race attempts and three spectating visits here had bought me some knowledge of the place; but under the gentle scrutiny of Shepherd's encyclopedic grasp of the course, my snippets of observation and recall are wilted to virtual uselessness. I am literally a newcomer.

“The key to doing well here,” Shepherd had said at the outset and repeated daily, “is in getting the sequence right. You must ride here with your mind ahead of the bike. You pull the bike along behind your mind, rather than riding it. To do that, you must know the circuit so well that you visualize every foot of it.”

Every foot? Can this be the secret of success here—the ability to “see” every foot? Can anybody actually do that?

Shepherd gravely assures me that it is more than possible, it is vital. So we spend hours building my mental card file, driving around in the Saab 9000 I come to think of as The Classroom, walking the course backward and forward, and talking, endlessly talking. Like a professor at the beginning of a semester. Shepherd announces that there will be a final exam, in which he will require me to talk him around the entire circuit. The exam will be given the night before the first practice, which is scheduled for Monday the 25th.

Today, the 22nd, the lesson focuses on The Line. Terry begins the session by telling me I do not need the entire road on the Island—that all I need is a continuous piece of it a yard wide and 37.73 miles long. “And when you begin going really quickly,” he smiles, “it’ll compress from three feet wide to one foot, and finally to six inches.”

I can see the sense of what he says, but as we work our way along the road, I wonder if what seems to make sense at 30 mph in a Saab will hang together at 130 mph on a Suzuki. The good shepherd assures me it will.

0720 hours, Monday, May 25th, 1987:

Shepherd proves to be right. Having passed his “exam” Sunday night in an exhausting, two-hour description of the course, I find the first practice an easy ride. Even though our first session has been slowed slightly by fog on the Mountain, and even though Shepherd has ordered that I not exceed 8500 rpm, my first lap is over 85 mph, my second at 88. As I pull into the pits, my orange “newcomer’s” vest spattered with bugs, I have the feeling that Manx I0l is working; that the combination of mnemonics, rote drilling of key sightlines, peel-off points and roadside markings, along with spine-chilling disaster stories from Shepherd’s past, is congealing into something like that magic, swooping, connected ribbon of asphalt I now call “The Shepherd Line.”

This is an important issue, because everything hangs upon it. To race here, you must first qualify; the Formula One race demands a lap at no less than 94 mph, and the Production event a shade over 90 mph. In addition, we are told that because the races are so over-subscribed, further cuts from the starting list will be made at the end of the week of practicing. So my first hurdle as a TT racer is qualifying—not all that easy for a newcomer. Many do not make the cut the first year.

But those who will fail do not have the formidable advantages Team cw has: a stunningly well-prepared, smooth-as-silk Suzuki that handles like a GP racer; and the man who prepared it and me—Terry Shepherd. As I peel off my orange vest, he exudes confidence that we will make the required speeds.

1355 hours, Saturday, May 30th, 1987:

It seems strange to be sitting here in the Formula One race lineup with a new number and no orange vest. But that’s what the team’s work and the Suzuki's untiring power have gotten us. As Shepherd predicted, we qualified for both races on the second day of practicing, leaving us three more practice sessions to continue learning the circuit.

Indeed, his strategy even calls for this six-lap, 226-mile F l race to be run as a kind of intensive practice session for our “real” race, the Production event. “Once you have the circuit well in mind, there’s no substitute for experience,” he says, “and no experience like that you get from a sixlapper.”

There’s more behind this approach than humility. In fact, because we’ve chosen to run our GSX-R750 absolutely bone-stock in the FI race, we’re giving away enormous power, tire and handling advantages to our competition, most of whom are pro riders aboard no-holdsbarred equipment built to the very edge of the rules. For us to run this race as anything but more practice would be foolhardy. So our goals are simple: keep learning the circuit, get in two pit stops for fuel to practice that critical operation, and, above all, finish.

As the clock begins its countdown to my go-time, it occurs to me how strange it is to think of the Fl TT—one of the most prestigious motorcycle road races in the world—as a preliminary to a shorter Production race. But as Terry noted, “There are many different races run on the TT course.”

The clock jerks, and ours begins.

1436 hours, Thursday, June 4th, 1987:

As I grunt with the g-loading and bottomed suspension around the superfast righthander at the bottom of Bray Hill, I peer through the fairing bubble to ensure that I crest the rise ahead well to the right. Too far left, and you do the spectacular “Bray Hill wheelie” made famous by Agostini in 1968, when he took his MV Three into the air there. Since I get unavoidably airborne no less than five times on a lap here, I don't need Ago’s jump, too.

But my mind is already at work on the Quarter Bridge approach, well over the hump. On new, still-slippery tires, the hard braking you have to do—downhill, at that—to second gear is no joke. So this time, I’m too cautious, and brake early. The Kawasaki 750 Ninja rider whom I’d nailed on the line swoops inside me as I tiptoe around Quarter Bridge. He’d obviously drafted me down Bray and into the braking zone. I tuck into his exhaust pipe and allow the Suzuki to wiggle on the new tires, gradually rolling on the power.

The short straight down to Braddan Bridge is a drag race with another slowish bit—third gear this time—that simply frustrates rather than amuses. 1 know my tires are still too new to take hard acceleration over the crown of the bridge, so I content myself with proving once again that this U.S.spec GSX-R has the motor on just about everything in the class. As we scream into the braking area at Braddan, I’m grinning at the fact that I'd had to roll off to stay behind the Ninja.

My grin slips as the Kawasaki rockets through the leftright, while the GSX-R slides on unscuffed rubber. I know that by the second mile, into Union Mills, the superb Michelins will be hot and sticky, but now more care is needed, so I bid goodbye to the Ninja and concentrate on the course.

From the exit of Braddan to the 90-degree righthander at Ballacraine is about seven miles of flat-out riding. You ride these seven miles under the paint, throttle hard against the stop, committing to ultrafast lines that demonstrate, as nothing else can, how inadequate any filmed or taped simulation of the course is. Your peripheral vision does the work at these speeds—upwards of 140 in our class—your central, or “foveal,” vision simply used to flick you from marker to marker to position the bike.

This is the kind of racing that defeats riders accustomed to short circuits, the kind in which the difference between committing fully with an open throttle and backing off slightly in doubt can make the difference between a 100mph lap and a 95-mph lap.

People unfamiliar with the course are always surprised that it’s ridden in such high gears. Partly this is the result of the photos taken over the years showing the racers in the slower pieces of the course—Quarter Bridge, Braddan, Ballacraine, the jump at Ballaugh, Sulby Bridge, Parliament Square, the Ramsey Hairpin, the Gooseneck, Signpost, Governor’s Bridge. But these are the exception on the TT course, not the rule; usually, the fast riders are in Top gear or the one below it, occasionally—as at Laurel Bank, Glen Helen, the twins Kerrowmoar and Glentramman, the first and second Waterworks, Guthrie’s Memorial, Windy Corner, the Bungalow, Creg-ny-Baa, Brandish and Signpost—dropping a gear or even two to get better drive, depending on the conditions and the powerbands they have to work with.

Because our CV-carbed Suzuki (the only U.S.-spec GSX-R in the event) has such phenomenal grunt—especially in the midrange, where the slide-needle carbs on the European versions cause a massive drop in response—I have enormous latitude in selecting gears, and can opt for a higher gear where other GSX-R riders are forced to rev into the red. This steadies the bike considerably, and makes true high-speed stuff great fun, almost stressless.

Such an asset is no small thing in the Island, where even the “short,” three-lap races subject you to considerable physical punishment on bumps, dips, jumps and “unnatural” bends you must literally force the bike into, such as the sweeping right that connects the hard, fast Filling Station lefthander at the 9th Milestone with the first Glen Helen turn. This one, like the four blind uphill lefts that comprise Cronk-ny-Mona (leading to the hard right at Signpost), demand the Suzuki to be muscled to the ground on the fairing and held there. A bike wants to arc out to the edge of the road in these sections, but the fast line and safety won’t allow it, because in both places, a lax hand or a slow entry will bring you to the edge of disaster with a curb or stone wall.

This is the TT course only the racer knows, the course of mental snapshots falling over in sequence, one image toggling another. The course of aural cues, too: of how the exhaust echoes off the left bank when you’re on the Mountain Mile, and off the right when you cross over Black Dub to the Black Hut. This is the TT course that no video can describe; only the mind can combine the thousands of data points to produce a successful race here.

And what is a successful race here? For Joey Dunlop, it’s a win. For me, it’s first of all a finish. This thought had driven me when a refueling error on our second stop of the FI race had resulted in gasoline gushing out past the improperly seated gas cap under acceleration or braking, coating me, my helmet and the inside of the fairing bubble with a sheet of fuel for most of a lap. I lost time not being able to fix it at any of the four impromptu stops I made; I lost time in riding straight-armed to avoid being washed in fuel or having to look through the barely translucent film on the bubble. But the need to finish kept me going, and finish l did.

Nothing like that happens on our 20-second pitstop at the end of my first lap of three in the Production race. I pull into the pits, the cw team gases the bike, cleans the screen and visor, and I pick up the yellow pit-lane “proceed” light all in what seems one smooth motion. I'm back on Glencrutchery Road again, the rhythm of the course almost uninterrupted, my ears still ringing with the wind noise of high speed.

Can words describe the next two laps’ ride? No more than a video can. But they can suggest, in a remote and coarse way, some of the enduring images and feelings. Like the immense pleasure of aligning so perfectly with the short bit of righthand curb at Barregarrow Crossroads that your line through what other people think is a left bend actually makes it a straight taken literally flat-out, just as it does at the bottom of Barregarrow, where g-forces as severe as those at Bray Hill crush you into the seat as you imagine your left shoulder kissing the pole on the left side of the road. Or like the satisfaction to be gained at what is now called the Thirteenth Milestone, but is actually two sections, Cronk Urleigh and Westwoods, where you do not “cronk early” into the visible right, but wait, then slam it down to take the second, invisible right, which puts you clear of the curb on the left, nicely on the new tarmac in the right lane so that you can execute the same maneuver through the uphill, blind left of Westwoods, knee into the wall, engine singing lustily and the speed-limit signs before the village of Kirkmichael heaving into sight as you reach redline in top—a wonderful reminder, if you’ve the time to reflect, on the sheer joy of what you are doing with a fast motorcycle on a sunny day: Going as fast as you can, perfectly legally.

There is nothing else like it, anywhere. The awareness of this is like a physical blow I endure the very moment the checkered flag signals the end of my Island racing for the year.

I coast to the return road, the three laps and 1 13 miles gone in what seems a handful of minutes. I idle the Suzuki along the tree-lined lane, waving to the spectators who clap for me as they do for each finisher. Aside from concluding beyond a doubt that this U.S.-model GSX-R750 need not apologize to any sportbike anywhere, I am unable to grasp what this means, this end to a fortnight of intense mental, physical and emotional activity. As I stop at the three orange coveralls of our team, I cannot imagine a better destination for our trip on Glory Road than this place, this moment, with these people.

One surprise remains, the unforseen bonanza of our long and winding road. As I halt, each member of the CYCLE WORLD crew, grinning, pumps my hand as if I had won—which I know I certainly have not. Paul Dean clarifies the reason for their smiles. “One-oh-one-point two!” he says excitedly, tapping his Casio.

Later, trying to sleep, 1 stare the ceiling of my room at the Douglas Bay Hotel, and consider the meaning of lapping the Isle of Man Mountain Course at over 101 miles per hour. Like the two bronze finishers' medals we’ve won, it’s only a symbol for something else, something less concretely beheld but maybe far more important.

As Shepherd had said when I made a rueful reference to our finishing 38th in a field of the 47 who survived the 750 Production race, averaging almost 10 mph less than the winner, conventional notions of winners and losers don’t really apply to the Island. He’d stopped me as I wondered aloud what it meant that, after more than an hour of racing, we’d finished 30 seconds behind Tony Rutter—winner of eight TTs, also on a GSX-R750—and 49 seconds behind Alex George, likewise GSX-R-mounted and winner of 3 TTs.

Shepherd had frowned into the distance, perhaps seeing again his own struggles here, and those of his friends and teammates who’d died on its hazards, and said quietly, “Anyone who finishes a race here is a winner.”

I stare into the dark ceiling of the hotel and at last understand what all this means. Like all the best courses, Manx 101 is not the end. It’s just the beginning.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe High Cost of Higher Performance

September 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeCoached To Success

September 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1987 -

Evaluation

Evaluation"The Care And Feeding of Your Motorcycle"

September 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupGrass-Roots Saviors?

September 1987 By Charles Everitt -

Roundup

RoundupShort Subjects

September 1987