Business In The Fast lane

RACE WATCH

One small company takes possession of motorcycling’s most valuable real estate: the quarter-mile

JOHN ULRICH

DAVID EDWARDS

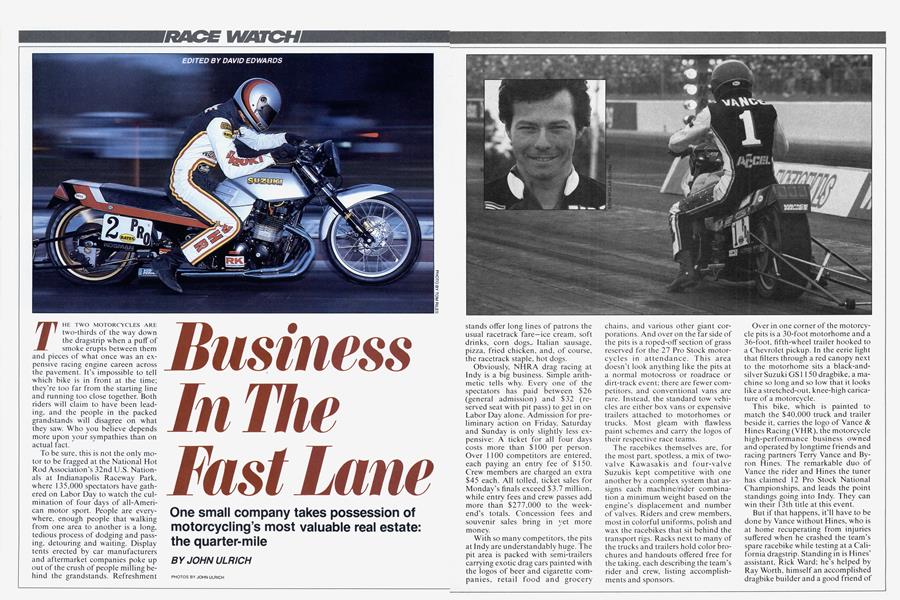

T HE TWO MOTORCYCLES ARE two-thirds of the way down the dragstrip when a puff of smoke erupts between them and pieces of what once was an expensive racing engine careen across the pavement. It’s impossible to tell which bike is in front at the time; they’re too far from the starting line and running too close together. Both riders will claim to have been leading, and the people in the packed grandstands will disagree on what they saw. Who you believe depends more upon your sympathies than on actual fact.

To be sure, this is not the only motor to be fragged at the National Hot Rod Association’s 32nd U.S. Nationals at Indianapolis Raceway Park, where 135,000 spectators have gathered on Labor Day to watch the culmination of four days of all-American motor sport. People are everywhere, enough people that walking from one area to another is a long, tedious process of dodging and passing, detouring and waiting. Display tents erected by car manufacturers and aftermarket companies poke up out of the crush of people milling behind the grandstands. Refreshment stands offer long lines of patrons the usual racetrack fare—ice cream, soft drinks, corn dogs,Italian sausage, pizza, fried chicken, and, of course, the racetrack staple, hot dogs.

Obviously, NHRA drag racing at Indy is a big business. Simple arithmetic tells why. Every one of the spectators has paid between $26 (general admission) and $32 (reserved seat with pit pass) to get in on Labor Day alone. Admission for preliminary action on Friday, Saturday and Sunday is only slightly less expensive: A ticket for all four days costs more than $100 per person. Over 1100 competitors are entered, each paying an entry fee of $150. Crew members are charged an extra $45 each. All tolled, ticket sales for Monday’s finals exceed $3.7 million, while entry fees and crew passes add more than $277,000 to the weekend’s totals. Concession fees and souvenir sales bring in yet more money.

With so many competitors, the pits at Indy are understandably huge. The pit area is packed with semi-trailers carrying exotic drag cars painted with the logos of beer and cigarette companies, retail food and grocery chains, and various other giant corporations. And over on the far side of the pits is a roped-off section of grass reserved for the 27 Pro Stock motorcycles in attendance. This area doesn’t look anything like the pits at a normal motocross or roadrace or dirt-track event; there are fewer competitors, and conventional vans are rare. Instead, the standard tow vehicles are either box vans or expensive trailers attached to motorhomes or trucks. Most gleam with flawless paint schemes and carry the logos of their respective race teams.

The racebikes themselves are, for the most part, spotless, a mix of twovalve Kawasakis and four-valve Suzukis kept competitive with one another by a complex system that assigns each machine/rider combination a minimum weight based on the engine’s displacement and number of valves. Riders and crew members, most in colorful uniforms, polish and wax the racebikes that sit behind the transport rigs. Racks next to many of the trucks and trailers hold color brochures and handouts offered free for the taking, each describing the team’s rider and crew, listing accomplishments and sponsors.

Over in one corner of the motorcycle pits is a 30-foot motorhome and a 36-foot, fifth-wheel trailer hooked to a Chevrolet pickup. In the eerie light that filters through a red canopy next to the motorhome sits a black-andsilver Suzuki GS 1 150 dragbike, a machine so long and so low that it looks like a stretched-out, knee-high caricature of a motorcycle.

This bike, which is painted to match the $40,000 truck and trailer beside it, carries the logo of Vance & Hines Racing (VHR), the motorcycle high-performance business owned and operated by longtime friends and racing partners Terry Vance and Byron Hines. The remarkable duo of Vance the rider and Hines the tuner has claimed 12 Pro Stock National Championships, and leads the point standings going into Indy. They can win their 13th title at this event.

But if that happens, it’ll have to be done by Vance without Hines, who is at home recuperating from injuries suffered when he crashed the team’s spare racebike while testing at a California dragstrip. Standing in is Hines’ assistant, Rick Ward; he’s helped by Ray Worth, himself an accomplished dragbike builder and a good friend of both Vance and Hines.

Vance uses a pay phone to call Hines no less than four times a day, reporting on track and atmospheric conditions, elapsed times and terminal speeds, and carrying advice and instructions back to Ward and Worth. Vance occasionally argues with Ward over the meaning of Hines’ instructions, the disagreement usually followed by yet another phone call.

Next to the Vance & Hines pits, a small crowd hovers, ogling the bike and helping themselves from a pile of posters stacked on an engine crate, posters that picture Vance on his racebike wheelieing out of a cloud of tire smoke. Anytime Vance is in view, people ask him to autograph the posters.

Worked into the NHRA program between runs made by four-wheel superstars such as Don “Big Daddy" Garlits, Kenny Bernstein and Tom McEwen, the bikes make qualifying passes on Saturday and Sunday. On Monday, the 16 fastest bikes pair off in elimination rounds until only two remain unbeaten; those two race for the win.

So tough is the competition that just getting into the program is an accomplishment. There is no practice; riders make their first pass in the opening round of Pro qualifying on Saturday. They get one more qualifying pass on Saturday, and two on Sunday. Eliminations begin Monday morning.

Not only is the competition tough, it gets tougher each year. At this event, it will take an 8.399-second E.T. to qualify. The difference between the fastest qualifier and the 16th qualifier will be a mere 0.228 seconds; the split from first to second will be 0.058 seconds; from first to fifth just 0.1 16 seconds.'

At Indy in 1985, an 8.400 would have been fourth-fastest qualifying time. In 1986, 8.400 won’t even get a rider into the program.

The competition wasn’t always so close. In the early 1970s, Terry Vance and Byron Hines worked together at RC Engineering, a high-performance parts company owned by motorcycle drag-racing pioneer Russ Collins. Hines developed into an engine-building genius, while Vance proved himself a highly skilled drag pilot. Together, they campaigned a double-engined Top Gas bike with great success, winning three championships in that class.

That was the beginning of a dragracing dynasty, a domination of Pro Stock competition that is without precedent. Starting in 1975, Vance (always with Hines as his tuner) won the Pro Stock championship every single year with the exception of 1979. And he did it on three different brands of motorcycles, using Kawasakis in 1975 and 1976, then switching to GS1000 Suzukis in ’77 and GS1100s in 1980. And in 1981, he not only won his usual Pro Stock title, but took the Top Fuel championship, as well.

After losing their Suzuki sponsorship at the end of the 1983 season, Vance and Hines ran only four events during 1984, beginning the year with a Honda CB1100F and ending it with a Kawasaki GPz 1000R Lawson Replica; they still managed to win the season championship. And at that point, Suzuki dealers were in such an uproar over the company’s loss of Vance and Hines that Suzuki relented and signed them to campaign a GS 1150 for the 1985 season. They responded by winning the championship again, and were then signed to a three-year contract that runs through the 1988 season.

Remarkably enough, Vance and Hines have even been able to turn their negative seasons into positive experiences. For example, 1979 was the only year in which they lost the Pro Stock title, but they still managed to start Vance & Hines Racing-a business that, thanks to their enormous success on the dragstrips and superb promotion of their feats by U.S. Suzuki, has grown at an astronomical rate. And it was during 1984, the season in which they were unsponsored and ran in only four events, when Vance made a rather disturbing, but eye-opening, observation that changed his racing and business philosophies: Pro Stock motorcycle racing—a class he and Hines had virtually owned for a decade and on which their business success depended heavily—was more exciting and more competitive when they didn’t show up. Their presence at the dragstrip was a key factor in their livelihood; yet their presence reduced the 'level of competition and made the class less interesting. They had to be there, yet being there hurt the racing.

“The problem was that only one or two teams were capable of winning,” says Vance, “and we were always one of them. We needed to win to promote our business, to make people realize we made good products. But in 1984, when we raced only four events, the class seemed to get better in our absence. Because with us out, there were more than just one or two guys who could win.

“Byron worked very hard for our championships,” Vance adds, “but he’s a very protective kind of guy. He kept all of his knowledge a secret. When you work as hard as he does, you don’t care to share your expertise with someone who wants all the glory without any of the effort. But once I realized that Pro Stock racing was better when we weren’t in it, I knew that there had to be more people capable of winning for the class to grow and become what it really should be. That could only happen if Byron supplied some of his secrets to buyers of Pro Stock motors. We had to start selling them motors with the same horsepower as the ones we were racing with.”

The decision was quickly made to do just that. And it didn’t take long before racers started sending in engines, paying at least $7500 for the building of a two-valve Kawasaki engine and at least $9500 for a fourvalve Suzuki.

At first, Hines wasn’t thrilled about the idea of selling his speed secrets to other racers, but he has come to be a strong supporter of the concept. “I get a tremendous amount of satisfaction from seeing the other guys do well,” he says. “It puts a lot of the fun back in the racing. It’s better to lose to one of our customers than to somebody who’s competing against us for business. And when one of our customers beats some major competitor who’s in the engine business, or even runs with him, that’s even better.”

One customer, “Pizza John’’ Mafaro from New Jersey, didn’t think the GS1150 engine he had bought from VHR in 1985 made enough power. So Hines accompanied Vance to an I DBA drag race at Ateo, New Jersey, at the end of the season, a race Vance hadn’t planned on running. With Hines setting up the bike and Vance riding, Mafaro’s Suzuki won the race and set a new elapsed-time record of 8.26 seconds.

That made a believer of Mafaro. “Except for Vance and Hines, everybody else is close,” he commented at Indy. “But if it wasn’t for them, everybody wouldn’t be so close. Everybody would still be running 8.50s and 8.60s.”

There are other racers at Indy who use Pro Stock motorcycle racing to promote their own high-performance businesses. Superbike Mike Keyte is one, himself a two-time Pro Stock champion who works in Southern Florida on a more modest scale than Vance & Hines. Superbike Mike Engineering has five full-time employees, including Keyte and his wife, Kathy.

“One of the things we’re really proud of is that we don’t have any Vance & Hines parts on the bike,” says Keyte of his GS1100 Suzuki. “We know that they make good stuff. But we just want to be different. They’re a tough act. They’re almost unbeatable. But not quite.”

Rick Stetson, owner of Harry’s Machined Parts of Framingham, Massachusetts, rides a Suzuki GS1100 built with Vance & Hines parts; and like several other racers at Indy, he sells services and Vance & Hines products in his local area. “A lot of racers have shops like mine, and they have to do well for the shop to do well,” says Stetson. “We have a following of customers, and what we learn racing, we turn around to benefit our customers. What we’re doing is just a smaller scale of what Terry and Byron are doing.”

Some of the riders at Indy have no connection to the high-performance business, and instead race as a hobby. A good example is Dave Schultz, who bought a complete Vance & Hines engine package and returns it to VHR for periodic rebuilds. “I run a real high-tech car operation,” he says, standing next to his Kawasaki. “This is really recreation to me. This is more my hobby, as opposed to guys like Terry or Mike. I used to race cars, but I quit it because it was my living. I just want to go out and enjoy myself.

“I used to build my own engines. I’ve tried it both ways, and I’d rather buy a complete package and just put my own touches on it. I think what Vance & Hines is doing will help Pro Stock. It sure didn’t hurt Funny Car racing when Keith Black started selling engines to other guys in the class. When you’ve got a field like this, when first to 16th is only 0.22 seconds apart, that’s only possible because you can buy a good Pro Stock engine.”

Indeed, whether professional or hobbyist, the majority of the riders at Indy—15 out of 27—have engines built or equipped by Vance & Hines Racing.

When qualifying rounds end on Sunday afternoon, Vance has qualified fastest, turning an 8.171 -second elapsed time with a 161.31-mph terminal speed. Keyte is second-fastest, at 8.229 seconds and 159.29. Schultz is third at 8,247 and 160.82. Mafaro is fifth with 8.287 and 161.03, just ahead of George Bryce, owner of Star Racing and a competitor of VHR, who turned 8.266 at 158.03 mph.

Of the 16 riders qualifying for the race, 12 use Vance & Hines engines. The ratio is the same after the first round of eliminations: Six of the eight survivors run VHR packages.

Vance, Mafaro, Schultz, Keyte and four others make it to the second round. Vance, Schultz, Keyte and Ed Dohrmann win in the second round and advance to the semi-finals. Only Keyte doesn’t have a VHR engine, so the ratio is still three out of four.

In the final, it comes down to Vance and Keyte. The winner will take home about $4400 in purse and contingency money, the loser about half that. But much more is at stake than the immediate winnings. This is a battle of businessmen as much as it is of motorcycle racers, a contest between commercial enterprises as much as between machines.

Rubber has built-up on the pavement at the starting line, laid down by pass after pass made by the cars. The rubber is thick and resilient and sticky, and it pulls and grabs at the shoes of crew members walking across it. Big Daddy Garlits has stepped it up in the Top Fuel car final to defeat Darrell Gwynn. McEwen has beaten Bernstein in the Funny Car final.

Vance picks the left lane; Ward plugs a remote starter-built from an automotive starter motor and pair of car batteries mounted on a cart—onto a special tip bolted to the end of the Suzuki’s crankshaft. The bike crackles to life and Vance drops it in gear, pulls forward into the burnout area and parks the rear tire on a patch of wet concrete. He revs up the engine and lets out the clutch, and the wide rear tire spins, visibly growing as it accelerates, the bike held motionless with the front brake. At first, there’s not much smoke. Then, quickly, the tire heats up and billows of white smoke pour off the spinning rubber, swirling up and forward and obscuring the tail section of the bike.

Vance releases the brake and the Suzuki darts forward, the tire screeching as it grabs the rubber already on the pavement. He stops, then shoots forward again, the rear tire spinning and screeching. He stops once more, then does another burnout, this time across the starting line. Ward runs out in front of him and pushes him backwards, across the line, into position.

In the opposite lane, Keyte and his wife go through the same ritual.

The bikes stage at the line and the engines rise in rpm. Keyte’s engine seems just a little ragged, a sound, Ward says, caused by Keyte’s predilection for very large carburetors, his willingness to trade some crispness at smaller throttle openings for big terminal speeds.

A blink and they’re gone with a crescendo of noise. Their semi-automatic transmissions move from one gear to the next at the touch of an airshifter button, without any interruption of power delivery, each shift discernable only by a change in exhaust note as the revs drop slightly.

It’s too close to call when the cloud of smoke appears. The left end of Keyte’s crankshaft explodes into Vance’s lane, taking parts of the engine cases with it. The lead-weightfilled alternator rotor rolls behind Vance’s wheelie bar and into the wall on the left side of the track. Keyte coasts across the finish line with a timeof 8.892 secondsat 110.82 mph. Vance wins with an 8.299 at 158.87. The victory also earns Vance the 1986 championship.

“I was in front of him,” Keyte says later, back in the pits. “I thought today was my day. I had him. I was just ready to push the button for fourth; it was just pulling 1 1,500 rpm. I felt a vibration and looked down and saw the oil spraying out of the galley and then straight back.”

Vance tells a different story. “He was never in front of me. No way. I looked over at him and his front wheel was right at my crank. It would have been close at the finish, no doubt. But would have and could have and did are different things. We deserved to win. We were the only guys who went 8.20s every round, and we had top mph the whole time. The trophy’s in our truck. But on Saturday afternoon, I wouldn’t have given you two cents for our whole operation.”

Throngs of fans file out of the track and clog local roads for miles in every direction. Vance came to the track with 6000 posters in his trailer; all that’s left is an empty box sitting on an engine crate. Along with the gear they brought with them, Ward and Worth have to load another two bikes and four engines into the trailer; racers dropped them off at the Vance & Hines pits for service and rebuilding.

Three weeks after Indy, at an IDBA motorcycle drag race at Ateo, Mason and his VHR-equipped Kawasaki beat Vance in the second round. Mason made it to the finals, where he lost to Marty Blades; Blades rides a Kawasaki put together with some Vance & Hines parts; there’s a VHR sticker on his bike.

That day, it was Blades who went home with the trophy in his truck. But when Ward loaded the Vance & Hines trailer, he put in three more engines than he came with. E3

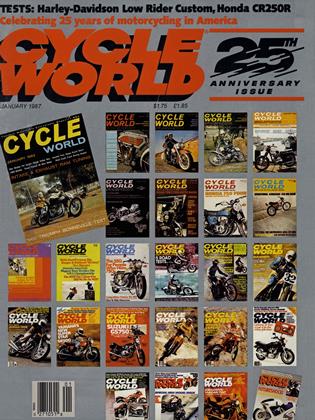

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

January 1987 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

January 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupAmerica's Changing Taste In Motorcycles

January 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

January 1987 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

January 1987 By Alan Cathcart