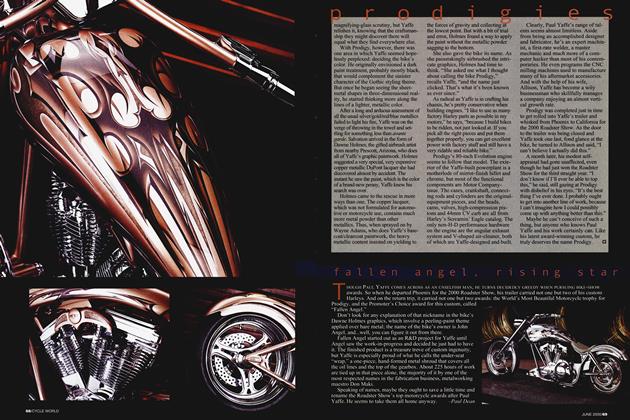

RETURN TO LAREDO

PAUL DEAN

Honda goes deep into the heart of Texas to break Cycle World's speed records

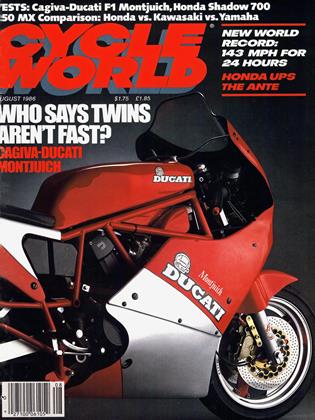

IF THAT OLD SAYING IS REALLY TRUE. IF RECORDS ARE meant to be broken, then Honda has merely acted out what fate intended. Because a factory-prepared Honda VFR750 has broken the world records that Cycle World had set just eight months earlier on a Suzuki GSX-R750.

Actually, “shattered” might be a more accurate description of what Honda did to those records. Cycle World averaged 128.303 mph for 24 hours on the GSXR, which was more than 1 1 mph faster than the mark set by a Kawasaki in 1977. But the VFR750 added yet another 15 mph to that record, averaging more than 143 mph for the 24-hour period. The VFR also bettered Cycle Worlds records for 6 and 12 hours by similar margins. And along the way, the viciously fast V-Four Honda also set 100-and 1000-kilometer records.

All of the VFR’s high-speed heroics took place at the Uniroyal Proving Grounds in Laredo, Texas, on the

same five-mile banked circle used by this magazine to set its records last September. Unlike our small-scale effort, though, Honda’s attempt was a megabucks affair involving more than 30 people and a cost-is-no-object approach to practically everything. The mechanical preparation of the bikes, as well as all the pit work, was handled by Team Honda Racing people, who brought along one of their 40-foot tractor-trailers outfitted to serve as a workshop and spare-parts warehouse, plus three big motorhomes to provide sleeping and eating quarters. Honda even brought six of its own scorers to work independently of the three FIM stewards who were on hand to certify the proceedings.

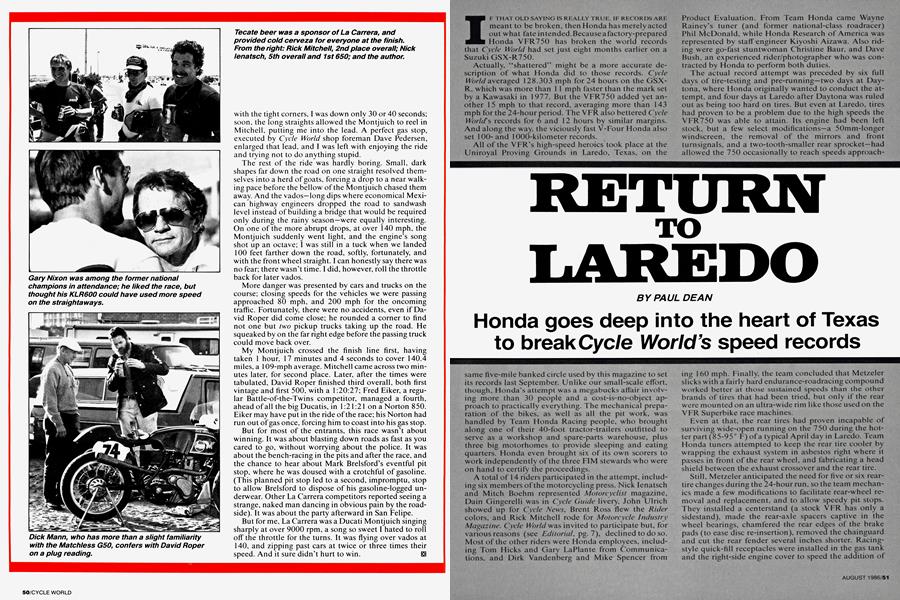

A total of 14 riders participated in the attempt, including six members of the motorcycling press. Nick Ienatsch and Mitch Boehm represented Motorcyclist magazine,

Dain Gingerelli was in Cycle Guide livery, John Ulrich showed up for Cycle News, Brent Ross flew the Rider colors, and Rick Mitchell rode for Motorcycle Industry Magazine. Cycle World was invited to participate but, for various reasons (see Editorial, pg. 7), declined to do so.

Most of the other riders were Honda employees, including Tom Hicks and Gary LaPlante from Communications, and Dirk Vandenberg and Mike Spencer from

Product Evaluation. From Team Honda came Wayne Rainey’s tuner (and former national-class roadracer) Phil McDonald, while Honda Research of America was represented by staff engineer Kiyoshi Aizawa. Also riding were go-fast stuntwoman Christine Baur, and Dave Bush, an experienced rider/photographer who was contracted by Honda to perform both duties.

The actual record attempt was preceded by six full days of tire-testing and pre-running—two days at Daytona, where Honda originally wanted to conduct the attempt, and four days at Laredo after Daytona was ruled out as being too hard on tires. But even at Laredo, tires had proven to be a problem due to the high speeds the VFR750 was able to attain. Its engine had been left stock, but a few select modifications—a 50mm-longer windscreen, the removal of the mirrors and front turnsignals, and a two-tooth-smaller rear sprocket—had allowed the 750 occasionally to reach speeds approach-

ing 160 mph. Finally, the team concluded that Metzeler slicks with a fairly hard endurance-roadracing compound worked better at those sustained speeds than the other brands of tires that had been tried, but only if the rear were mounted on an ultra-wide rim like those used on the VFR Superbike race machines.

Even at that, the rear tires had proven incapable of surviving wide-open running on the 750 during the hotter part (85-95° F) of a typical April day in Laredo. Team Honda tuners attempted to keep the rear tire cooler by wrapping the exhaust system in asbestos right where it passes in front of the rear wheel, and fabricating a head shield between the exhaust crossover and the rear tire.

Still, Metzeler anticipated the need for five or six reartire changes during the 24-hour run, so the team mechanics made a few modifications to facilitate rear-wheel removal and replacement, and to allow speedy pit stops. They installed a centerstand (a stock VFR has only a sidestand), made the rear-axle spacers captive in the wheel bearings, chamfered the rear edges of the brake pads (to ease disc re-insertion), removed the chainguard and cut the rear fender several inches shorter. Racingstyle quick-fill receptacles were installed in the gas tank and the right-side engine cover to speed the addition of

vital fluids during pit stops, which would have to occur about every 18 laps.

And so, at 1:30 p.m. on Saturday, April 26, a pair of VFRs—a 750 and a 700—set off around the Uniroyal track, with Cycle World’s records squarely in their sights. But it didn’t take long for trouble to intervene. About a half-hour into the attempt, the 750's rear slick started chunking so badly that you could hear dangling pieces of rubber slapping on the ground as the bike roared past. The VFR was immediately signaled into the pits for a new tire; and the Metzeler people got temperature readings from the old tire of 285 degrees Fahrenheit—about 40 or 50 degrees hotter than considered acceptable.

Less than a half-hour later, the tire-chunking problem

occurred again, so the decision was made not to run the 750 wide-open until the hottest part of the day had passed. Thus, average lap speeds for the 750 were backed down from just over 150 mph to around 145 mph.

About y/z hours into the event, any concerns about tire problems were rendered moot when the 750’s engine blew. “It just went ‘ka-boom,’ ” said Rick Mitchell, who was aboard at the time. The VFR was towed back to the pits—a violation of FIM rules, which would have disqualified the bike anyway—and quickly put out of sight in the Team Honda trailer. The Honda personnel had been instructed before the event not to disassemble any engine that might fail, to instead send it intact back to Japan; so they were non-committal about what might have gone awry, although speculation among them ran from a bro-

ken connecting rod to a dropped valve.

Undaunted, they quickly readied another record bike by taking all of the “trick” parts from the blown bike and installing them on a back-up VFR750. And at 5:30 p.m., only about an hour after the engine failure, another VFR750 began its own assault on Cycle Worlds records.

With the exception of a few relatively minor interruptions, the remainder of the record attempt went fairly smoothly. Dain Gingerelli’s night vision was pressed to its limits when the 750 blew a headlight fuse just after dark, and Mike Spencer’s courage was put to the test at 3:40 a.m. when he centerpunched a badger at over 150 mph. The 750 had its front end bounced about a foot into the air but escaped unharmed; Spencer, however, suf-

fered a few loosened teeth and the badger was a total write-off. Dirk Vandenberg ran the 750 out of gas right at the 12-hour mark, and a chunked tire in the late morning reminded everyone that the 750’s lap times had to be backed off once again. And when the 700 was one hour from its finish, one of its chain rollers parted company.

All told, those incidents, and the corrective action they required, had only minimal effects on either bike’s record-breaking pace. And at 2 p.m. on Sunday afternoon (daylight savings time had gone into effect that morning), the VFR700 sped across the finish line for the last time, having broken the 24-hour record by more than 10 mph with an average speed of 138.907 mph.

Matter of fact, the 700 had also broken the 6and 12hour records and the 100and 1000-kilometer marks,

but each time, the 750 had come along AVi hours later and wiped them out. And that is precisely what happened with the 24-hour record, as well. At 6:30 p.m., Christine Baur piloted the 750 across the start/finish line for its final tour of the track, completing a 24-hour run that had netted an average speed of 143.108 mph—over 4 mph faster than the 700 had posted, and almost 15 mph better than Cycle Worlds record speed.

After the 24-hour run was over, Honda attempted to break the existing 1-hour record of 150.452 mph that had been set at Daytona in 1974 by Gene Romero on a TZ750 Yamaha. The rider who had consistently delivered the fastest lap times-the 110-pound Aizawa-was put aboard the 750 and told to “go for it.” But after only

a half-dozen laps, the attempt was aborted. Pre-attempt calculations had shown that the bike would have to average more than 155 mph to allow enough time for a fuel stop (the VFR could run only about 35 or 40 minutes on a full tank), and Aizawa was running only in the 152-153 mph range. Another day, perhaps.

Besides, the VFR750 had already demolished every record Honda had set out to eclipse. And Honda still had two more issues to deal with—namely, establishing that the engine in the record-setting VFR750 was indeed a box-stocker; and demonstrating that the nearly 3500 wide-open miles the VFR had run at Laredo had not rendered the engine a clapped-out, unridable mess.

To that end, Honda immediately turned the victorious VFR750 over to the people least-inclined to give the bike

any benefit of the doubt: Cycle World. After all, if it had taken a modified engine to eat our records alive, we wanted to know about it, even though there are no rules prohibiting non-stock engines in world-record runs. So, without the bike ever leaving our sight after the completion of its last lap around the track, we climbed aboard the VFR and rode it the 1500 or so miles back to our offices in Newport Beach. And once there, we completely disassembled the engine to inspect every single part and measure all critical components for wear.

What we found—or, in some cases, did not find—was impressive. First, the world-record bike ran just as quickly and smoothly as the VFR750 test unit we still had back in our shop—a fact we established as soon as we

got home. And we were able to find no non-stock components inside the engine, nor any evidence of hand grinding and polishing. As far as we were able to determine, the engine was bone-stock. Not only that, after measuring piston and ring wear, bearing clearances and valve lash, we concluded that the amount of wear the engine had sustained was minimal. There was no scoring visible anywhere, and most of the clearances were still well within the range recommended for assembly purposes.

Honda, therefore, is to be congratulated for a truly spectacular achievement. Admittedly, we at Cycle World are not ecstatic about having our world records taken away, but we have to give credit where it is due. And Honda has not only demonstrated that the VFR750 is one fast motorcycle, but that it’s one tough motorcycle.S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue