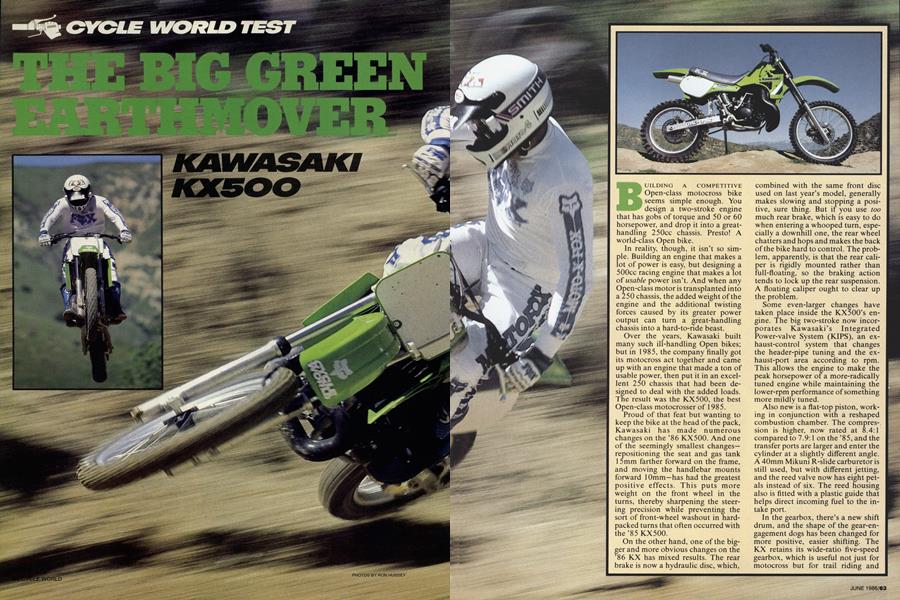

KAWASAKI KX500

CYCLE WORLD TEST

THE BIG GREEN EARTHMOVER

BUILDING A COMPETITIVE Open-class motocross bike seems simple enough. You design a two-stroke engine that has gobs of torque and 50 or 60 horsepower, and drop it into a great-handling 250cc chassis. Presto! A world-class Open bike.

In reality, though, it isn’t so simple. Building an engine that makes a lot of power is easy, but designing a 500cc racing engine that makes a lot of usable power isn’t. And when any Open-class motor is transplanted into a 250 chassis, the added weight of the engine and the additional twisting forces caused by its greater power output can turn a great-handling chassis into a hard-to-ride beast.

Over the years, Kawasaki built many such ill-handling Open bikes; but in 1985, the company finally got its motocross act together and came up with an engine that made a ton of usable power, then put it in an excellent 250 chassis that had been designed to deal with the added loads. The result was the KX500, the best Open-class motocrosser of 1985.

Proud of that feat but wanting to keep the bike at the head of the pack, Kawasaki has made numerous changes on the ’86 KX500. And one of the seemingly smallest changes— repositioning the seat and gas tank 15mm farther forward on the frame, and moving the handlebar mounts forward 10mm—has had the greatest positive effects. This puts more weight on the front wheel in the turns, thereby sharpening the steering precision while preventing the sort of front-wheel washout in hardpacked turns that often occurred with the ’85 KX500.

On the other hand, one of the bigger and more obvious changes on the ’86 KX has mixed results. The rear brake is now a hydraulic disc, which, combined with the same front disc used on last year’s model, generally makes slowing and stopping a positive, sure thing. But if you use too much rear brake, which is easy to do when entering a whooped turn, especially a downhill one, the rear wheel chatters and hops and makes the back of the bike hard to control. The problem, apparently, is that the rear caliper is rigidly mounted rather than full-floating, so the braking action tends to lock up the rear suspension. A floating caliper ought to clear up the problem.

Some even-larger changes have taken place inside the KX500’s engine. The big two-stroke now incorporates Kawasaki’s Integrated Power-valve System (KIPS), an exhaust-control system that changes the header-pipe tuning and the exhaust-port area according to rpm. This allows the engine to make the peak horsepower of a more-radically tuned engine while maintaining the lower-rpm performance of something more mildly tuned.

Also new is a flat-top piston, working in conjunction with a reshaped combustion chamber. The compression is higher, now rated at 8.4:1 compared to 7.9:1 on the ’85, and the transfer ports are larger and enter the cylinder at a slightly different angle. A 40mm Mikuni R-slide carburetor is still used, but with different jetting, and the reed valve now has eight petals instead of six. The reed housing also is fitted with a plastic guide that helps direct incoming fuel to the intake port.

In the gearbox, there’s a new shift drum, and the shape of the gear-engagement dogs has been changed for more positive, easier shifting. The KX retains its wide-ratio five-speed gearbox, which is useful not just for motocross but for trail riding and high-speed, grand prix-type events.

By itself, the addition of KIPS should have made for a smoother powerband and an easier-to-ride Open bike. But the new KX500 also has an ignition flywheel that is almost two pounds lighter than the one used last year. And that reduction in flywheel effect has made the engine so much more quick-revving and explosive that it’s hard to feel the benefits of the KIPS. Until a rider learns to torque the KX out of hard-packed, muddy or other kinds of slick turns in a taller-than-normal gear, he can expect to smoke the rear tire or to find the front wheel clawing in the air.

Not surprisingly, the new engine works best in deep sand, in good loam or on tacky surfaces. Any time there is lots of traction, the engine will launch the bike out of corners like a cannon shot, and propel it down the straightaways faster than last year’s KX500. But when the traction is less than optimum—which is most of the time for riders in many areas around the country—last year’s heavier flywheel would make the bike easier to ride. And tight corners that could easily be taken in third gear with last year’s 500 require second gear and a careful use of the throttle on the ’86.

This year’s KX500 still uses KYB suspension components, but they, too, are changed. The fork has slightly different damping values, and now incorporates a Travel Control Valve (TCV) intended to minimize bottoming when landing from stadium-type jumps. And, indeed, the TCV works nicely when the bike lands from 15 feet in the air. But the fork is harsh over medium-sized bumps and smaller jumps, and the front tire skips across the smaller, choppier bumps. The TCV idea undoubtedly is great for anyone planning to ride in a lot of stadium events, but for other types of races the compression damping is simply too stiff.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that the problem is easy to fix. After we drilled a hole in each damper rod (the third hole up from the bottom only goes through one wall of the rod, so we drilled the same-size hole through the other side of the rod), most of our complaints went away. >

In the rear, a new KYB shock has a 2mm-larger shaft and a 6mm-larger bore diameter. These refinements increase the shock’s strength and eliminate fade under most conditions. The rebound damping is adjusted by turning a knob at the top of the shock, and the separate lowand high-speed compression-damping knobs are still on the shock reservoir. We set the rear-suspension sack to four inches, put the high-speed compression knob on the Number One position, turned the low-speed knob four clicks out and left the rebound damping in the standard position.

Once we got a few break-in miles logged on the KX, the shock worked nicely. The rear end seldom bottomed, and the ride was controlled and comfortable.

Several other changes have been made to the newest KX500 to improve its reliability. The adjustable strut on the rear suspension is larger and stronger; the chain guide is bolted in three places instead of two; the fenders are ribbed for strength and are wider for better protection; and the silencer packing material is longer-lasting. Seems like trivial stuff, but a failure in any one of these different areas could cause a poorer finish or a dnf.

Besides, as you have just seen, changes that seem trivial often are anything but. Kawasaki’s engineers have made numerous changes to the KX500 in an honest attempt to keep it ahead of the competition; but while they have succeeded in many ways by building a faster, better-steering MX bike, they’ve failed in several others. And many of those failures —the more-explosive engine, the chattering rear brake, the harsh front forkare the result of changes that, if not exactly trivial, are certainly not revolutionary, either.

So in the end, the ’86 KX500 is quite competitive as it rolls out of the crate, and an easy modification to the front fork makes it even more so. But no longer does it have a competitive edge over the competition. Matter of fact, Honda’s new CR500R undoubtedly has a competitive edge over the KX500.

Like we said, building the best Open-class motocrosser isn’t easy. E3

KAWASAKI KX500

$2849

View Full Issue

View Full Issue