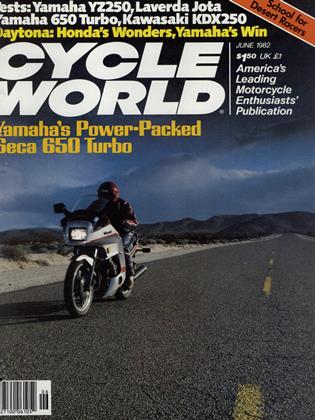

YAMAHA TURBO SECA 650

Power, Good Looks and a Nice Personality.

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Remember those wonderful ads in the comic books where the 97 lb. weakling went to the beach only to have some guy with big muscles and no neck kick sand in his face and walk away with the girl? Our skinny hero then went home to take a mail order course in muscle building and returned to the beach in glory, reclaiming his girl and shoving the bully in the face. America has always loved the underdog who gets mad and is suddenly infused with the power to get even or seek justice. Superman, Popeye, the Incredible Hulk and a long list of other professional sleepers have all amused us with

their sudden, unbelievable powers.

In the case of the Seca 650 Yamaha didn’t exactly start with a 97 lb. weakling, but turbocharging that bike has certainly enabled it to push any number of larger and heavier machines in the face. Like the Honda CX500 Turbo just before it, the Yamaha Turbo Seca 650 demonstrates much of the two-stage personality we’ve come to expect from the modest hero.

Ridden around town with the tach needle anywhere below 5000 rpm, the bike runs like a nice, well-behaved modern 650 Four. Okay, it has a flashy aerodynamic fairing and sculptured bodywork and complex instrumentation, all of which make it a little heavier than the average 650, but not enough to matter. That sporty 750 at the traffic light may get away a little quicker than the Yamaha, but that’s to be expected. One is a 650, after all, and the other is a 750. Nothing wrong with that; a 650 is a good all-around bike, neither too big nor too small, and it gets you where you’re going.

That’s below 5000 rpm.

Above 5000 rpm the Yamaha Turbo begins to do strange things. Instead of following the 750 down the road at a respectful distance, the Turbo suddenly pulls into a metaphorical phone booth, sheds its glasses and mild mannered reporter’s suit and steps back onto the street.

On boost.

In a flurry of fast-building revs the Yamaha reaches deep down within itself and discovers about 30 more bhp on the way to redline, flinging the bike down the road in a heady surge of arm-straightening acceleration. If the throttle is held open and gears are shifted up, the turbo quickly redlines in 5th gear (good for about 127 mph) and it’s necessary to back off just a bit to keep from over-revving. The 750 suddenly finds itself with riding company and the nice, well-behaved modern 650 Four has become a new machine. An instant superbike, if you will. The Turbo Seca transforms itself from motorcycle to superbike and back again with ease, and the transformation is simply controlled by the right wrist. No phone booths, full moons or other props are needed.

Yamaha did much of its early experimentation with turbocharging on a fuelinjected XS11 engine, but eventually concluded there was little point in boosting peak power on an engine that had about as much performance as most riders—and most rear tires—could use. It’s generally more interesting to have an agile midsized sport machine with big bike performance than to have a big bike with an overabundance of power. The giant killer mentality again.

It was then decided to take the Seca 650 and attempt turbocharging it up to the approximate power output of a 1000. The goal was sort of a best-of-both-worlds motorcycle, a bike with the economy and lively personality of a carbureted 650 Four for “normal” riding, but with the potential to match the performance of almost any machine on the road when the boost was dialed up. While the actual numbers bring the bike up short of true 1000 level performance, turbocharging has made the XJ650T, as it is designated, a very exciting 650 Four.

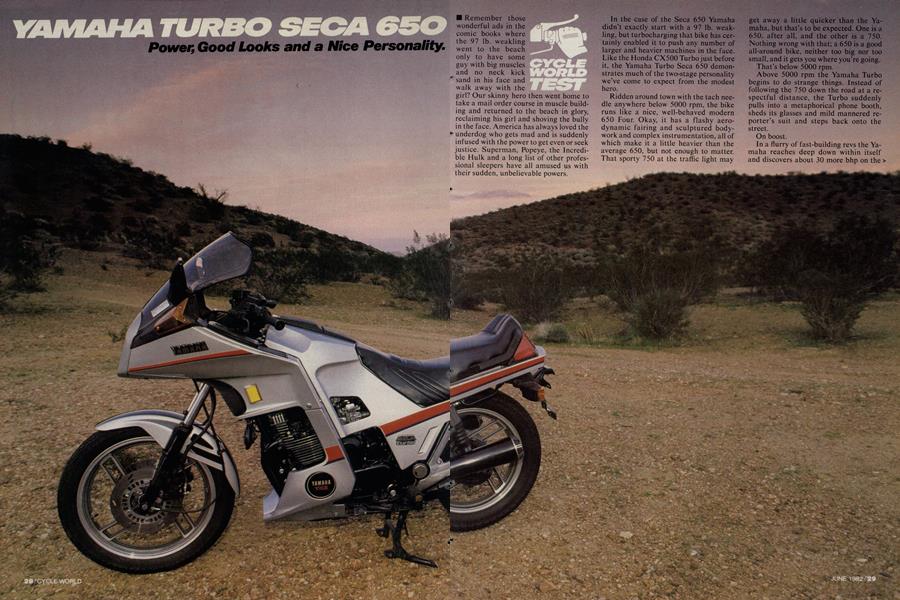

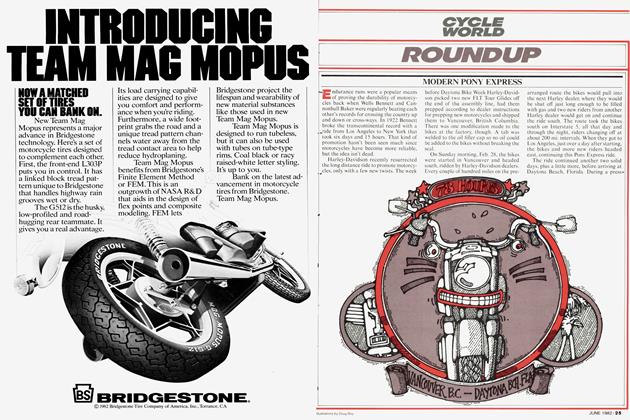

Though the fairing and bodywork of the Turbo Seca lend the bike a fairly exotic and complex look, the turbocharger and its associated plumbing have been grafted on in a reasonably clean and simple fashion. Exhaust gases leave the engine through header pipes with inner walls of stainless steel and are funneled into a manifold beneath the engine. The manifold pairs the #1 and #4 exhaust pipes into one pipe, and the #2 and #3 pipes into another before they reach the manifold. This allows the exhaust pulses to be evenly spaced as they enter the turbo, driving it more efficiently. A wastegate bleeds off excessive pressure when the boost goes too high, feeding excess exhaust into the right side muffler. The left muffler receives only exhaust gases straight from the turbo.

The turbocharger itself is a Mitsubishi TCO3-06A unit and is claimed by Yamaha to be the world’s smallest. With a turbine diameter of only 39mm, it can spin safely up to 210,000 rpm. The turbine shaft rides in a bearing-within-abearing, as do most other modern turbos, reducing the destructive speed that any one bearing surface might have to withstand. The bearings and shaft between the turbine and the compressor are pressure lubricated with engine oil from the main oil gallery on the crankshaft. There is an added scavenging pump in the engine to draw oil away from the turbo.

The compressor side of the turbo draws air in through the air cleaner under the seat, pressurizes it and sends it into a surge tank just in front of the carbs. The four 30mm C V carbs are not just any C V carbs, but are themselves pressurized from the outside in, so to speak. They have special drillings around the throttle shafts to provide a back-pressure against the turbo boost, preventing leakage or misting of fuel and air from joints and shafts in the carb bodies. The float bowls also receive regulated pressure from the surge tank to stabilize fuel levels. Fuel is supplied by a pump, cable driven off the end of one camshaft, and the regulator sends excess fuel back to the tank.

Yamaha has worked hard to eliminate the dreaded “turbo lag”, a characteristic that is more damaging by word of mouth than it generally is to actual riding characteristics of the machine, as in the case of the Honda Turbo. In any case, Yamaha has come up with a clever way of eliminating the condition. Turbo lag appears when the throttles are whacked open at low boost, when the engine is drawing air faster than the turbo is supplying it. This results in a momentary intake vacuum that causes the engine to go flat. Yamaha ' engineers have worked around this by installing a set of reed valves between the surge tank and the air cleaner. If the throttles are opened and there is a temporary intake depression, the reeds flap open and allow a normal flow of air to the carbs. As boost pressure catches up and -builds in the surge tank the reeds flap shut, sealing the boost pressure to the carbs. The surge tank also houses a relief valve, so if a waste gate malfunction or other problem causes overboost in the surge tank, a poppet valve opens up and releases the excess.

Simply turbocharging an engine and then standing by for more power is not enough, of course. A turbo makes an engine much more sensitive to detonation, and the added power imposes loads and temperatures well beyond those found in the non-turbo version of the same engine. To eliminate the detonation problem, Yamaha uses an electronic vacuum advance/knock sensor. One part of the electronic vacuum advance unit senses vacuum in the intake tract and tells the ignition governor unit, an electronically precise way of doing what most vacuum advance units have always done, i.e. retard ignition when the throttles are open and the engine is under load. The other part of the advance system is a knock sensor located in the cylinder head. This picks up the first faint rattle of detonation in the combustion chambers and slowly retards the ignition timing just enough that the knock ceases. An engine makes its best power when timed just" short of destructive detonation, and the knock sensor moves the timing around to keep it at that point, regardless of load, throttle opening, or fuel octane rating. Motorcycle and car racers who have holed pistons may wonder where this sytem has been all their lives.

The 650 engine itself has been substantially changed to handle the added turbo load. Compression ratio has been dropped from 9.2:1 on the regular Seca to 8.2:1 on the Turbo. Pistons are forged instead of cast aluminum and the crown material is 30 percent thicker to with-* stand the heat. Added piston cooling is provided by an oil drilling in the connecting rod that sprays oil onto the bottom of the piston crown. The crank has been double-drilled for better oil flow to the rods and the surfaces of the big end rod bearings have been given oil retention grooves, though bearing material is unchanged, as are rod and pin dimensions.

To supply oil for all these extra grooves and holes, as well as to the turbo itself, the oil pump drive ratio has been stepped up to provide 60 to 70 percent greater flow through the lubrication system, though pressure remains the same as on the Seca 650. An oil cooler has also been added.

The driveline, starting at the clutch, has been strengthened considerably. The clutch is a Seca 750 unit, but with heavier springs with 9mm more free length for a higher preload. The self-adjusting cam tensioner from the 750 is also used on the Turbo. Outer transmission shaft bearings are the same size, but are made of upgraded materials for higher load. All gear ratios and sizes are the same as those on the Seca 650, but the gears have been given an improved heat treatment for more durability. The crankcase is essentially unchanged, except for an extra drilling for the turbo oil line and the addition of cast iron inserts around the left side driveshaft bearing in the transmission.

That old devil heat has been responsible for the remaining changes in the engine. The cylinder head fins are larger for more cooling area and the head itself is now a heavier casting for better heat dissipation.

The basic frame and dimensions on the Turbo are identical to the 650 Seca’s, but the frame has a few added brackets to handle the turbo installation and the fairing and bodywork. The fairing, seat and body moldings, of course, are the most distinctive visual features on the Turbo, and Yamaha claims the appearance to be as much a result of wind tunnel testing as styling. Beyond looking good, the fiberreinforced plastic fairing was designed to provide lower drag than an unfaired machine, downforce to prevent front wheel lift at speed, and comfortable wind protection for the rider.

Yamaha has provided us with extensive charts and graphs to prove the aerodynamic efficiency of the fairing. These make interesting reading, but wouldn’t mean much if the fairing didn’t perform as intended. Luckily it does, in most respects. One of our editors spent two days at the Yamaha test track in Japan, riding the Turbo under a variety of track and wind conditions, and found that even on the very long downhill straight, running flat out in fifth gear, the bike demonstrated excellent stability. Crosswinds and gusting had much less effect on the bike than you would expect from a machine with a road fairing, and the fairing made it easy to hold on and relax at speeds approaching 130 mph.

Wind protection is very good. The fairing does an excellent job of keeping air blast off the knees and lower legs, and directs most of the wind flow around the rider’s hands even though the fairing does not extend as far out as the grips.

There is virtually no wind pressure on the shoulders and torso at any speed. The only minor failing of the glass work is that a small amount of turbulence hits tall riders about mid-helmet. Crouching behind the fairing eliminates some of this, but then the rider has to peer at the road through the highly-angled acrylic wind-* screen, which, like most big pieces ot plastic, cannot be described as optically correct. Wind protection is still far better than most small sport fairings provide, but the serene calm behind the rest of the fairing makes us wonder if a small lip or upsweep on the end of the windscreen might not complete the job.

The screen itself is connected to the fairing with polycarbonate screws, designed to snap off on impact if the motorcycle is involved in an accident. The fairing has a small lockable storage bin on either side, large enough for gloves, cigarettes, etc. but not much more. The shell between the rider’s knees is not the gas tank, but a plastic cover designed partly for looks and partly to mold a comfortable spot for the rider’s legs and knees. The gas tank, an unadorned black 4.2 gal. steel container sits beneath the cover in normal gas tank position. The* seat is held on with a lock and lever arrangement, (keyhole at the left side of the seat), and it is removable rather than hinged. There is a small tool and document bin beneath the rear of the seat as well as a locking security chain in its own tray. Removal of all the bodywork is neL. ther complicated nor quick and easy. It’s just a matter of taking several minutes with a phillips screwdriver and a 10mm wrench and removing all the anchor bolts.

The Yamaha has regular tubular handlebars, covered by an angular black plastic molding, and the footpegs are rearset. The Turbo was a comfortable fit for nearly everyone who rode it. The bars are low and sporty, but not so low that much of the rider’s weight is carried by his arms and shoulders, and the footpegs work well with the seat and the body moldings to provide a good “knee grip’’ sensation when riding. While the seat appears to be swoopy and downswept, it has very little step to restrain the rider from moving fore and aft at will. Passengers found the rear seat comfortable and several mentioned it was nice to have the seat handles and upswept rise at the end of the seat, particularly when the engine came up on boost.

Suspension on the Turbo is air assisted, front and rear, with single filler caps and crossover tubes on both. The Kayaba forks are not equipped with anti-dive, but don't really seem to need it. The stock front springs, along with the range of air adjustment provide good compliance over bumps without excessive softness or dive. In addition to air assist, the rear shocks have four-way adjustable damping set by turning chrome collars at the tops of the shocks.

Starting the Turbo on a cool morning takes full choke and a bit of cranking on the electric starter. The choke lever is handlebar mounted on the left side, and full choke holds the engine at a high idle that can be backed off after a few seconds of running. If the engine is warmed up for a couple of minutes, the bike can be ridden away with the choke switched all the way off, or if you are in a hurry it also runs well at about half setting. Out on the road, the Yamaha warms up and runs right very quickly.

Yamaha has succeeded at its goal of building a turbo that takes nothing away from the bike’s bottom end performance. Up to 5000 rpm, the 650 runs pretty much like the non-turbo Seca; i.e. very •well. It has good acceleration, crisp carburetion and no flat spots or hesitation at any throttle setting. If you bought a Turbo Seca without knowing it was turbocharged you could spend your whole life shifting gears at 5000 rpm and merely believe that you owned a nice smooth 650 Four with a trick fairing.

Given that same lack of knowledge, you might occasionally run it up to 6000 rpm and come to believe the bike had a rather peaky set of cams and a lot of top end power. From 6000 rpm to the 9500 rpm redline, the rush of power would lead you to suspect you’d been rear-ended by a speeding truck, or accidentally triggered a hidden JATO bottle. The Turbo Seca really moves out at full boost, and it seems to use up the tach as quickly in fifth gear as it does in second or third. Rush, in fact, is a word that might have been coined to describe the upper end behavior of the Seca Turbo. The transition to boost is not dangerously abrupt or tricky, but it leaves no doubt that Something Has Happened in the engine.

There is a lot of whirring and spinning going on in the Turbo engine at speed, and the fairing amplifies a good deal of mechanical noise and delivers it to the rider. As a result, the Yamaha never sounds sedate and laid back, even ridden around town. The bike emits a combination of racy, hyper gear and turbine noises, something like a Ferrari Flat-12 in low gear, and always sounds as though it’s waiting around to pounce or launch itself. This is exciting if you like it and tiring if you don’t. Our guess is that most Turbos buyers will be the sort who like it. There are plenty of virtually silent, low key motorcycles already in the market for people who want them. The Turbo is a busy motorcycle, and when the throttle is twisted it sounds busy.

Handling of the Turbo Seca is difficult to fault. Yamaha has the traditional riseand-fall shaft drive problem worked out to where the presence of a shaft is barely detectable on the 650. The bike is dead stable on fast straights and heels over into corners with the same confidence and directional stability. Steering input is light and predictable and the bike goes where it is pointed, holding a line well even in rough corners. True to the Turbo concept, the bike feels light, narrow and agile for a machine with big bike performance.

The only difficulty in riding the Turbo fast is adjusting to the use of boost coming off corners. If revs and boost are allowed to drop entering a corner, power doesn’t come on hard until you are well past the apex and on your way out. On a big sweeper this means you get a very hard launch toward the exit of the corner and correct line becomes critical to staying on the road. But once you become accustomed to keeping revs up and using the turbo when you want it, the application of power becomes sheer entertainment, and it’s almost a letdown to climb back on a normally carbureted 650 with normal, linear acceleration. Use of the turbocharger, like other thrills, is addictive.

While it’s true that a turbocharger can make for a very exhilarating 650, ultimate performance figures for the Yamaha put it just a little bit below the average sporting 750 Four. Those who are used to the instant, arm-tugging torque delivered by a 1000 or an 1100 at nearly any rpm should bear in mind that a turbo 650 is still only a 650 until the turbo starts spinning. At lower rpm the lunging throttle response is simply not there. The 650 Turbo is a twopart composite of adequate acceleration followed by thrilling acceleration, rather than a brute from idle on up. Riding it fast demands a little more finesse.

The 650 Turbo turned a 12.67 sec. quarter mile at 106.13 mph and did 121 mph in the half mile. The non-turbo Seca 650 we tested in April ran 12.78 sec. at 103.68 mph and 117 mph for the half mile. That’s^ not a huge difference, but it has to be qualified by noting that the Turbo Seca, at 552 lb, is 63 lb. heavier than the Seca, and it is also pushing a full-coverage fairing through the air. No tucking in for more speed. What you get is what you get. Drag strip figures also tend to average out per-^ formance, but don’t tell you much abouF the fun factor when the turbo comes up on boost, with all that extra muscle on the upper end. A good 750 Four will get you from point A to point B faster and quicker, but without quite the same adrenalin stimulation, or comfort.

Brakes on the Turbo are identical to those on the regular Seca, which is to say they are strong, well-balanced and easy to modulate, with a 7 in. drum at the rear and a pair of 10.5 in. discs at the front. Due to the added weight of the Turbo, stopping distances were a few feet longer but still good, at 36 ft. from 30 mph and 141 ft. from 60 mph.

Mileage figures on any turbocharged machine will vary, of course, by how much and how often full boost is used. On our 100 mi. test loop it was pretty difficult to use the turbo for more than a few seconds at a time without overshooting the, legal speeds we observe to standardize the mileage test. So the 54 mpg figure is about what you can expect from legal city/highway riding. The surprising part is that we regularly averaged 45 to 50 mpg in fast mountain road riding, both two-up and solo. On the racetrack, where boost can be maintained for longer periods of time, it’s possible these figure.^ would drop considerably. But on the highway or canyon road the Turbo simply runs out of road (or into police) too often for the bike to stay on constant boost. In actual riding, the turbocharger is more a there-when-you-need-it accessory than a constant drain on your mileage.

The fuel tank holds a reasonably generous 4.7 gal, meaning the Turbo can be nursed well over the 200 mi. range with careful riding, and well below that when the rider is caught in the grip of wild abandon. The Turbo has a spring loaded hatchcover on the fiberglass body shell with the real gas cap beneath it. The cajf is a locking screw-off type, and there is a drain in the gas cap well, so overfill runs out a little hose beneath the bike rather than all over the tank.

For instrumentation the turbo has a 12,000 rpm tach and the usual laughable 85 mph speedometer. The panel also coi"i tains an LED checklist for battery water, oil, lights, fuel and sidestand. Each blinks once when the engine is started and stays on with a red warning light that flashes if anything is wrong. As a further precaution, the engine kills if a gear is engaged while the sidestand is down. The warning lights have a reset button. If the button is pushed once the flashing red light goes to a less distracting constant red; pushed twice, it turns the red light off, which is even less distracting. There is also a check button to make the safety checklist run its full gamut of warning lights, for your riding entertainment.

The LED fuel gauge shows four rectangles when the tank is full, three when it’s 3Á full, and so on. In one respect, this fype of instrument is a little more deceptive than a straight needle gauge. You take off on a ride with two rectangles showing half full, and in your mind you imagine half a tank of gas. Five miles from home one of the little rectangles goes out and, like magic, you now have only a quarter of a tank, forcing a reassessment of your riding plans. This complaint assumes you need a fuel gauge at all, of course. Motorcyclists got along without them for years. But the show/no show gas gauge is more misleading than a needle type, as long as you’re going to have one.

* Levers and handlebar instruments are all conveniently arranged and work very well. The turn signal switch is Yamaha’s down-for-off type with a built in timer, which is one of the nicest to use when you get used to it. The fairing mounted mirrors are close enough together to show quite a bit of shoulder relative to road, but can be angled out so the only hard spot to see is right behind the bike. The finish on nearly everything is first rate. The fairing, body shell, seat and metal castings are all executed in a way befitting a special motorcycle.

In all, the Yamaha Turbo Seca is a motorcycle that does everything its designers intended and does it very well.

It offers all the advantages of its Seca 650 bloodline: handling, economy, agility, narrowness, light weight and good brakes. And overlaid on that solid citizen foundation is that ability to jump into the phone booth and come out charging. The pnly place the Clark Kent analogy breaks down, of course, is in the appearance of the Turbo Seca. Yamaha didn’t waste any time trying to disguise the 650’s intentions with mild-mannered styling.

The Turbo Seca joins the Katana Suzuki and the Honda Turbo in crowd-

fathering honors, and it may even outraw those two exotics in winning the riveted attention of random bystanders, motorists, schoolchildren, cops and other motorcyclists wherever it goes. Those who don’t like being stared and pointed at may want to buy some other model. They’ll be missing out on a lot of fun, Though. The Yamaha is a bike with the performance to back up its exotic good looks.

YAMAHA TURBO SECA 650

$4999