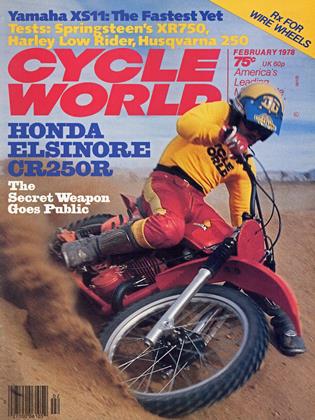

HONDA ELSINORE CR250R

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Long-Awaited New Motocrosser Turns Out To Be Better Than New

Trust Honda. There was a time when Elsinore meant winner. Then there was a time when Elsinore meant winner only because there was so much competition equipment on the market that a fullrace Honda motocrosser could keep up with stock bikes from the other factories. Then came a time when weeks went by without an Elsinore getting close enough to smell the champagne. The name for the hot new setup was RC and even if the factory team had come alive, it didn’t matter to the privateers because the Elsinore wasn't an RC and the RC wasn't for sale.

Here we are full circle. Honda proudly presents the . . . Elsinore.

And it’s an RC, never mind what the labels and the factory tell you.

The Honda guys are a bit touchy about labels. When they called to say the test 1978 motocrosser was ready, we said It’s an RC, right? and they said No. But we’ve been looking at the RC works bikes at the races for two seasons now and when the factory crew whipped off the dust cover and there was a tall Honda with a carefully shaped little engine, left-hand kick, righthand chain, red frame and bodywork and even engine, there was no doubt. It says Elsinore CR250R because the name and numbers signify a production racing Honda. The R means Replica and that means a racer as close to team specs as it’s possible to sell.

It also means the best handling motocrosser we’ve ever ridden.

How it works and why it works so well begins with the frame. It’s chrome-moly tubing, as the competition Hondas usually are, with a massive single downtube and backbone. The lower tubes are butted up against the downtube and the rear frame members are smaller tubes flattened and welded into the backbone at almost the same place where the forward mounts for the cantilevered shocks feed their loads into the chassis. The frame approaches careless pragmatism; the welds are strong and not neat, the tubes are trimmed off but not dressed out. There are gussets and reinforcing plates w here needed. No effort has been spared to make the frame stiff and durable. No effort has been made to make it look pretty, saving the red color.

The planning show’s up elsewhere. Coming from the backbone down to the rear of the cylinder head is a head steady, a brace to dampen engine vibration by feeding it into the frame. It makes the engine’s life easier and if it gives the chassis more work to do, well, the chassis is built to take it.

The long swing arm rides on roller bearings and the swing arm pivot is only 80 mm away from the countershaft. It’s that close to reduce the change in chain tension between extremes of wheel travel. Because of that, there is no chain tensioner. The chain, a D.I.D. TR model, one of the best on the market and only recently offered in #520 size, is controlled only by a roller wheel and two rubber strips on the arm.

Steering head bearings are tapered Timken bearings and the rake angle is 28 deg. 45 min., a precise measurement that says the engineers spent a lot of track and computer time getting exactly the right setting. The 2.2-gal. fuel tank is aluminum, rather taller and shorter than normal, because the seat is longer than normal. Somebody at the factory has been watching the races. It’s standard practice to scoot up onto the tank in tight turns, now' that the long-travel bikes have become tall and thus hard to turn. So Honda’s solution is to give more seat.

Suspension is deceptively simple, or maybe the other factories are deceptively complicated.

The Showa-made forks have 37-mm. stanchion tubes, machined between the triple clamps, with a leading axle and full-

length boots. There are no air caps and the tech reps said there was no need to tune the forks with air, oil or springs.

In the shop, the Showas were not like other forks. They use standard-but-long stanchion tubes and sliders, with the sliders containing a wide upper bearing, an O-ring, a dual lip seal and a scraper. The damper rod is actually a damper unit, with a thin, solid rod inside the damper unit. This inner rod is threaded at the top and bolts to the stanchion tube cap.

The rear shocks follow the same principle. They are long, a full 17'/2 in. There is 6 in. of shock travel. The shocks are gas charged but they don’t have reservoirs or extra finning or any of the techniques the rival factories and aftermarket people have been using for the past few years.

Before riding the CR, we expected the suspension to be this simple because the engineers know most racers replace the shocks as soon as they can.

After riding the CR, we’re not so sure.

As a side note to our suspension lab tests, the testing is done with a standard # 15 oil, to keep the tests themselves on a baseline. But in this case, the oil in the CR forks was lightweight, #5 as far as we could tell, and the oil appears to have some sort of anti-friction additive.

The tests therefore show higher damp-> ing rates and seal drag than was experienced at the track.

Feature news for brakes is that the rear is a full-floating unit, with the backing plate rotating on the axle and the locating rod fastened to the rear of the frame, in alignment with the swing arm pivot. What this makes is a parallelogram that isolates the brake forces from the suspension forces.

The alloy hubs are conical, with magnesium backing plates. The rear brake and sprocket are on the same side, a good way to save weight and something the English did years ago (that means we’re glad it’s being done again). The engine side covers are magnesium. The rest of the bike is less exotic (and expensive) stuff. Test weight of the CR250 is 224 lb., which is competitive but well above the legal minimum. They have kept the cost and weight down together by a series of impressive touches, like hollow bolts for the swing arm pivot, axles, shifter shaft, etc., nearly every place such a weight-saving device is possible.

If the men who make the frame are practical and not artistic, the men w'ho designed the engine are both. The CR250 is, repeating, new only in that it hasn’t been in production. In actual experience, it’s been tested for two years.

With a bore of 70 mm and stroke of 64 mm, the CR250 is oversquare, contrary to the usual modern practice but in keeping with the high state of tune. Compression ratio is 7.3:1, measured in the usual Jap-

anese method of comparing combustion chamber volume to displacement of the chamber and the cylinder when the exhaust ports are covered and compression actually begins. (European practice is to measure with piston at bottom dead center, as everybody does with four-strokes.) The CR250 has a 36mm Keihin carburetor and a piston-port reed valve with six steel petals. Bore is chrome-plated and the piston has two rings.

There are seven ports; two intake, four transfer and one exhaust. The latter is bridged, to reduce the risk of a snagged and broken ring.

The transfer ports are different. There are the usual ports between crankcase and cylinder. There are also ports cast into the barrel and feeding the crankcase from the intake tract just inside the reed valve. This technique allow s use of a solid skirt piston, and thus contributes to engine durability. (The limiter on the reed valve holder, by the way, is drilled for lightness. Amazing!)

The CR250 is rated at 36 bhp at 7500 rpm. The engine makes power and it makes it at the high end of the rev scale, normal for an oversquare engine and not a bad thing for a racing engine, although it does make demands on the rider.

Ignition is CDI. with the windings mounted inside a dished flywheel, that is, the rim is outboard of the center while most flvwheels are the other way around. The ignition timing can be adjusted from the outside, by rotating the cover on the case.

The cylinder head is a true radial, with the spark plug offset to clear the exhaust pipe but firing in the center of the combustion chamber. The exhaust pipe is neatly routed down, up, around and out. There is no interference with the rider, remarkable in view of the narrowness of this machine.

This must be one of the smallest 250s ever. The cases are shaped around the crank, etc., as closely as possible. The built-up crank carries counterweights that lack being full circle only because they’re shaped and relieved to allow' a smooth flow' of air and fuel from crankcase to transfer ports. Weight of the engine, without carb, is 56 lb. This weight includes the aluminum shift lever, aluminum kick starter lever (really) and oil.

The 1978 CR250 engine is not at all like the earlier units. The most visible change is kick start on the left, where the Europeans have had it forever. The different difference with the CR is that the starter still works on the primary drive, so the rider can re-start in any gear. The chain is on the right, just like the RC engine. The 5-speed transmission uses a wet clutch and has a fairly narrow gear spread, which is normal in motocross.

The.carb breathes through an airbox carefully positioned around the frame tubes, with two intakes and a two-stage foam filter.

The controls show evidence of race testing. Bars are chrome-moly, with a black finish. The levers are cast metal, which is not unbreakable but which also doesn’t flex in the manner of the replacement plastic levers used by riders who break the metal jobs. The grips are shaped right and are softer than we can recall Honda offering before. The cable ends are covered with little slip-off boots. The front brake has an extra return spring and the rear brake cable has a small protective bar where it passes the frame. (There is no provision for pedal height adjustment, which seems to be the only oversight on the CR.) Fenders are plastic, wide and red all the way through. The fuel filler opening is large enough so the level can be monitored while the fuel is being poured in, a useful thing to have. The test bike arrived with the petcock reversed, that is, the control lever was behind the fuel line; looks like too much trouble except to those of us who’ve shut off the fuel flow with a careless knee.

Dismantling the CR led to some conclu-

sions: The engine is light. Almost every washer, spacer, fitting, etc., is aluminum, while most bikes use steel. Much effort has been expended keeping weight down as much as possible.

But not to make the CR light. The complete machine is average in weight. Honda’s designers have added strength and weight. The frame is heavy. So, at 9VA lb., is the swing arm. In short, the weight is being put to good use.

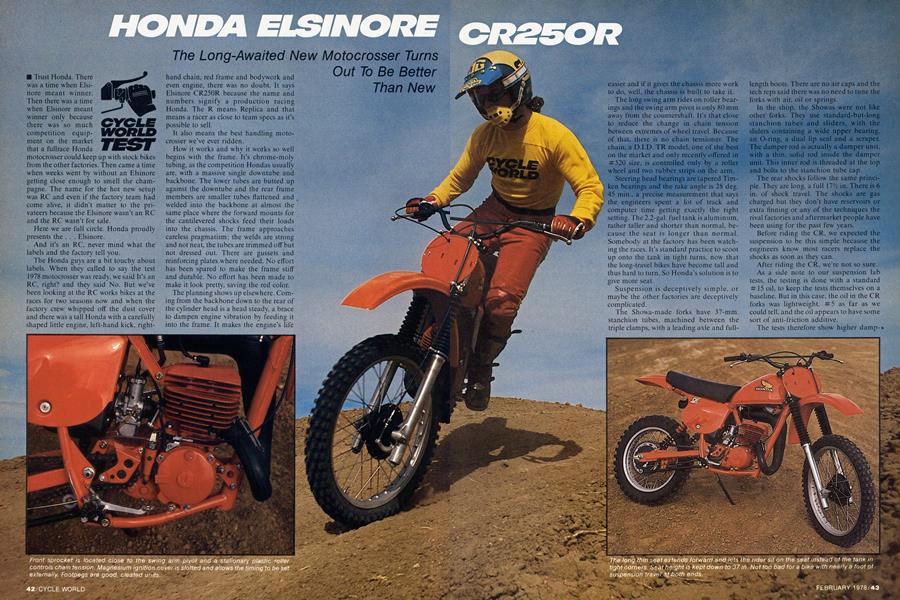

Now comes the good part. The CR feels right, as soon as the rider’s leg goes over the seat. The seat height is 37 in., but that’s a bit misleading. The suspension is soft and the bike settles an inch or two with the rider’s weight. A man of average height can touch the ground without effort. The bars, levers, pedals and such are just where you’d expect them to be.

All the old complaints about left-hand kick start vanish instantly. The CR lever swings out freely but locks out of the way. It doesn’t hit the frame, the rider has a clear kick and, best of all, the CR engine starts with one or two kicks, hot or cold.

The Elsinore CR is not a beginner’s machine. This is a racing bike and it’s intended for serious competition only. First, the CR250 develops all the power claimed. Next, the power is at the high end of the rev range, say from 4 thou on to the 7500 rpm peak. Finally, the engine is pipey. Below 4000 it will pull the bike out of its own way. Above that, quick as a switch, all the power arrives instantly, aided by the light and quick throttle: just what the expert racer wants when he comes out of a turn, but not what the play rider needs halfway up a rocky hill.

The brakes are super. No other word fits. The largish front brake has power and control. The rear brake is fully floating, both in the engineering sense and because the brake torque works to keep the rear wheel on the ground, rather than in the air. The rider comes slamming over the whoops, cuts the throttle and stands on the brake and the CR stops. Like that.

The suspension is best of all, in fact makes the Elsinore CR the best handling stock motocross bike we’ve ever ridden.

About that: Because the Elsinore was brand new and was released for test before it was shown to the public or even Honda’s dealer network, we could not race it. We promised not to allow the public to even look at it.

So the Elsinore went to 395 Cycle Park, Adelanto, California. Track owner Don England let us use the track for the day, in private. The raceway has a long motocross track, a short motocross track, a TT track, a scrambles course and a banked half-mile oval; every dirt surface known to man, so we could try the Elsinore under a variety of conditions. Because we don’t usually test that far from home base, we took along two other new 250 race bikes as a control group.

The Dunlops on the test bike did not win our hearts, being not as suited to loose sand and hard-packed adobe as are Metzelers. But with tire pressure dropped to 9 psi, the tires worked well enough to show that the Elsinore is magnificent.

The CR steers better than any motocrosser we’ve tested. Corners can be squared, taken in a slide or any combination thereof. The light front end doesn’t wash out or push. The tire stays planted on the ground unless the rider wants it in the air. Riders with markedly different styles felt as if the CR was designed to match their techniques.

The CR flew straight off the jumps, no loop and no twitch, and landings are pillow soft.

Almost 12 in. of front travel and 11 of rear travel must be experienced to be appreciated.

With the steep 28-deg.-and-a-fraction of rake, the pre-CR prediction would have been a great machine in the tight places and a handful over sand whoop-de-doos at speed. Not so. The Elsinore feels better in sand than many a desert sled. Even with the throttle chopped shut in the midst of the ridges, there was no tendency to jump about. Taller gearing, a larger tank and a skid plate would make the CR an instant desert winner.

At full speed, which would work out to 75 mph or so, the Elsinore needs some weight shift; sitting forward keeps the front wheel down and tracking. But it will stay in a straight line.

All that wheel travel at both ends gets used. At the extremes, landing after a long jump, banging across w'hoops flat out, banking off hard berms, the forks and shocks will bottom. Just barely, with such control that the rider wasn’t aware of w hat the onlookers could see and hear. This is the w^ay it should be. as if the bike doesn’t use all its travel at maximum, then it isn’t using all the suspension the engineers have provided.

The springs and damping work out perfectly. The test experts w^ere most impressed by the way the CR would track straight across diagonal bumps and dips. The wheels are always on the ground and the long, soft travel combines with the stiff frame and swing arm to eliminate pitch and wobble. Under heavy braking in whoops the CR doesn’t kick up or out. We’ve never before tested a motocrosser that didn’t have this to some degree.

The power and light front end let the rider lift the front at will, with a tweak on the grips and a tug on the bars. But when the CR comes out of a corner and the tire hooks up, the suspension and geometry put the rear wheel into a squat. The front wheel stays down and the rider can steer. Again, we’ve never had a racing bike with such power that was so easy to control in this situation.

The Elsinore will slide. Balance, again. On the flattrack the experts looked like Springer and Roberts, putting the rear wheel out in a classic drift and balancing on the edge, under power right to the exit and wham, the tire bites and the CR rockets away. A tracker is supposed to be this controllable at speed. A motocrosser isn’t.

The praise could go on all day. Darkness fell before w^e could feel any fade in the suspension. The staff cowtrailers enjoyed the CR even if they don't have the skill to use all the power. The experts, our desert racer and professional motocross man, liked the Elsinore as soon as they fired it up. The longer they rode it, the better they liked it.

Honda’s new Elsinore sets a new standard. If pressed, we could criticize the short shift lever, which is too easy to tap into the wrong gear. Everything else is as suited to motocross racing in expert hands as it can be. If the CR250 needs a taller gear and a softer engine for play riding and enduros, well, if Honda’s planners are as smart as we know they are, an enduro bike based on this machine is bound to be in our futures.

Price? The test bike was loaned out of the development shop and the marketing men don’t know yet. But it’s bound to be competitive. Even if the Honda sets a new standard for the class, Honda will have to meet the price level of its mass-production rivals.

Meanwhile, the Honda Elsinore CR250R puts everybody else one giant step behind.

Swing arm is heavy, 9¼ lb. with chain guide.

ELSINORE

CR250R

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsThe Troubleshooters

February 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

February 1978 By A.G. -

Roundup

RoundupShort Strokes

February 1978 By Tim Barela -

Features

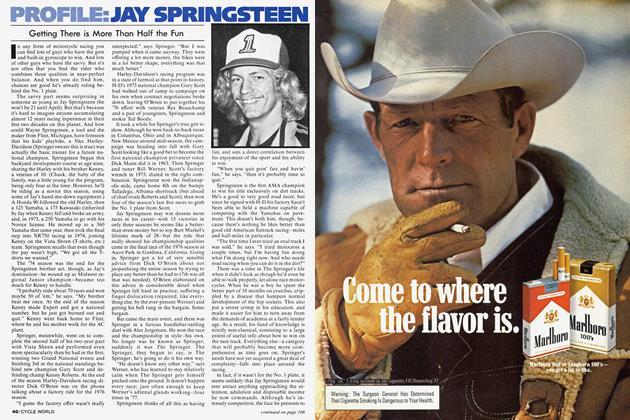

FeaturesProfile: Jay Springsteen

February 1978 -

Competition

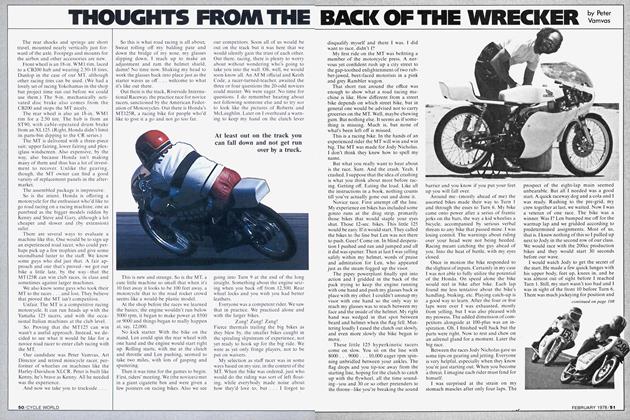

CompetitionThoughts From the Back of the Wrecker

February 1978 By Peter Vamvas