EDITORIAL

Dark clouds, silver linings

UNLESS YOU’VE BEEN LIVING UNDER A flat rock in Fiji or are just back from an extended vacation on Pluto, you probably know about the crisis the motorcycle industry is facing: Bike sales over the past few years have gone flatter than a week-old beer. As a result, the people who make motorcycles and affiliated products, as well as the people who sell them, have had to make sweeping changes in the way they do business just to stay in business. And before it’s all over, many of them will have to enact even more drastic measures if they hope to survive. So to say that this is not the best of times for the motorcycle industry is like saying that 1974 was not the best of times for Richard Nixon.

If you’re wondering what could have brought about such life-threatening problems for motorcycling, don’t look for one big, catastrophic knockout punch; there has been none. Rather, the industry has been put on the ropes by a combination of smaller blows—a governmental leftjab, a couple of financial uppercuts, a social right-cross. Individually, none of these impacts would have been all that damaging; but together, they have sent the industry reeling.

One of the main causes of these woes is the ever-increasing expense of buying a motorcycle. Not only has normal inflation kept sticker prices climbing, but other factors, including stepped-up tariffs and the dramatic devaluation of the dollar, have sent them skyrocketing. And after buyers clear that hurdle, they somehow have to cope with insurance premiums that often are prohibitively high.

Such financial roadblocks are compounded by the fact that more and more “baby boomers” are aging to the point where motorcycles no longer are important to them. These members of the post-WWII population explosion have constituted a major part of motorcycling’s core group of enthusiasts throughout the sport’s 20-year growth period; but now that they’re approaching middle-age, they gradually are becoming less active in motorcycling. And their replacements, the current crop of 18-to-35year-old males—the segment of the population with the most potential for motorcycle ownership—are considerably smaller in number.

Not only that, they also aren’t as

intrigued by motorcycles as previous generations have been, mostly because they have grown up in the electronic age rather than in the mechanical age. We’re now producing fewer and fewer “gearheads” and more and more “bytebrains,” kids who don’t know a crankshaft from a camshaft but who can score 90 trillion on any video game and write a computer program complicated enough to thoroughly confuse everyone over the age of 20. So while motorcycles were once considered a “cool” form of transportation, young people today are drawn toward other, lower-cost, less-mechanically intimidating forms, such as scooters and mopeds.

As if all that weren’t bad enough, motorcycles today have to compete with a lot more discretionary-income purchases, as well as more automobiles, than ever before. In the late Seventies, when motorcycle sales were at peak levels, cars were at their all-time slow, ugly, boring worst. The automobile industry had not yet figured out how to build an interesting car that also met federal requirements for exhaust and noise emissions, and for 5-mph bumpers. So a lot of performance-minded people of that period turned to motorcycles, which were not only real hot-rods, but real bargains, as well. Today, however, with so many attractive, affordable performance cars on the market—and with all of the problems associated with buying a motorcycle-bikes generally come out second-best when people have to choose between one or the other.

Okay, so that’s the bad news; but if you think that I’m forecasting noth-

ing but gloom and doom for motorcycling, you’re wrong. Most motorcycle experts feel that the industry will rebound from these dark ages, but that it won’t happen in just a year or two; it will take five, six years or more to get healthy again. It will also take new and creative marketing and promotional strategies to start getting more people riding bikes.

Even at that, the industry is unlikely ever to be quite as big and as fast-moving as it once was. We’ll see fewer models from each manufacturer, models that will not be drastically changed every year or obsoleted every two or three years. And it will take much longer for leading-edge technology to get from the R&D department to the showroom floor.

But so what? Would that be so bad?

I think not. Imagine a worst-case scenario in which no all-new models would be introduced for, say, the next 10 years, and that every bike now on the market were to remain fundamentally unchanged during that period. You know what? They’d still be the most incredible collection of motorcycles imaginable. They’d still be the most awesome performance vehicles ever offered for sale to the general public.

What’s more, imagine just how refined today’s bikes would be after 10 solid years of being manufactured without major changes. Imagine how much more competently bike-shop mechanics would be able to repair them, and how much more thoroughly parts rooms could maintain spares for them. Imagine how much less a bike might cost when you bought it, how much more it’d be worth when you sold it, and how much less you would spend maintaining it in between.

Naturally, if this were to happen, a small percentage of hard-core enthusiasts would be terribly upset. And motorcycle magazines would have to find something to talk about other than which new model is the recipient of the monthly fastest-bikewe’ve-ever-seen award. But in the end, it would help bring new people into the sport while not chasing as many away from it.

If that sounds like bad news to you, please explain to me why; because to me, it’s the best news I’ve heard lately.

Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupWatching Them Watch the Show: Cologne '86

December 1986 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

December 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

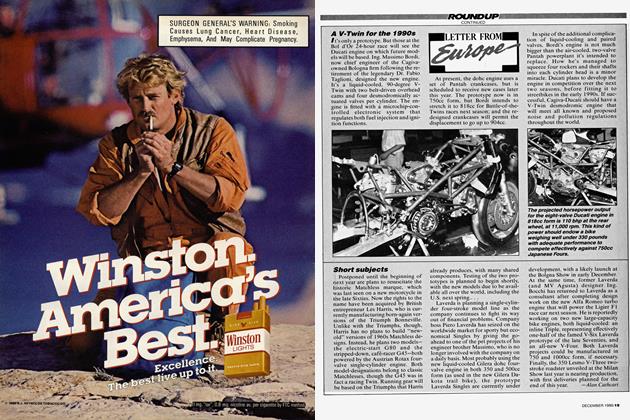

RoundupLetter From Europe

December 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

1987 Previews And Riding Impressions

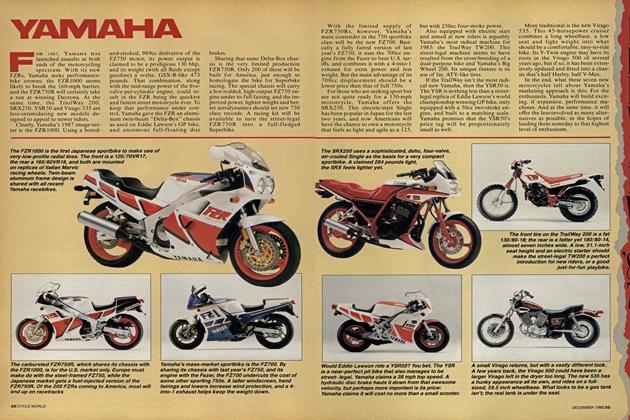

1987 Previews And Riding Impressions1987 New Model Preview

December 1986 -

1987 Previews And Riding Impressions

1987 Previews And Riding ImpressionsYamaha

December 1986