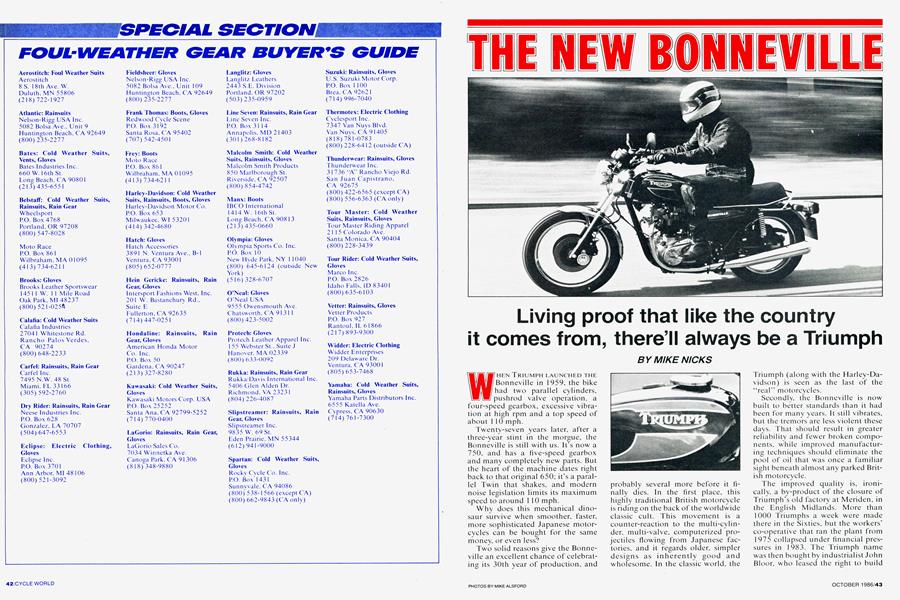

THE NEW BONNEVILLE

Living proof that like the country it comes from, there'll always be a Triumph

MIKE NICKS

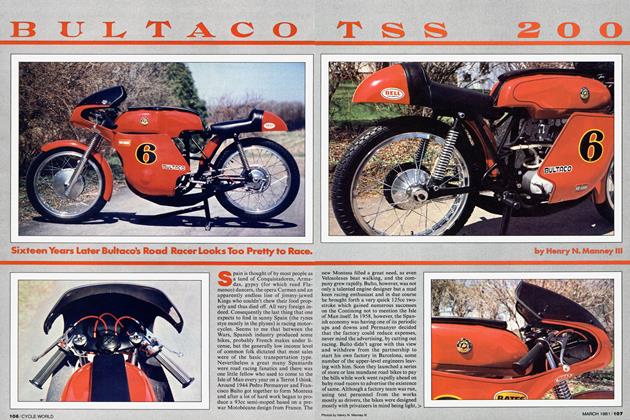

WHEN TRIUMPH LAUNCHED THE Bonneville in 1959, the bike had two parallel cylinders, pushrod valve operation, a four-speed gearbox, excessive vibration at high rpm and a top speed of about 110 mph.

Twenty-seven years later, after a three-year stint in the morgue, the Bonneville is still with us. It’s now a 750, and has a five-speed gearbox and many completely new parts. But the heart of the machine dates right back to that original 650; it’s a parallel Twin that shakes, and modern noise legislation limits its maximum speed to around 110 mph.

Why does this mechanical dinosaur survive when smoother, faster, more sophisticated Japanese motorcycles can be bought for the same money, or even less?

Two solid reasons give the Bonneville an excellent chance of celebrating its 30th year of production, and probably several more before it fi nally dies. In the first place, this highly traditional British motorcycle is riding on the back of the worldwide classic cult. This movement is a counter-reaction to the multi-cylin der, multi-valve, computerized pro jectiles flowing from Japanese fac tories, and it regards older, simpler designs as inherently good and wholesome. In the classic world, the Triumph (along with the Harley-Davidson) is seen as the last of the “real” motorcycles.

Secondly, the Bonneville is now built to better standards than it had been for many years. It still vibrates, but the tremors are less violent these days. That should result in greater reliability and fewer broken components, while improved manufacturing techniques should eliminate the pool of oil that was once a familiar sight beneath almost any parked British motorcycle.

The improved quality is, ironically. a by-product of the closure of Triumph’s old factory at Meriden, in the English Midlands. More than 1000 Triumphs a week were made there in the Sixties, but the workers’ co-operative that ran the plant from 1975 collapsed under financial pressures in 1983. The Triumph name was then bought by industrialist John Bloor. who leased the right to build the Bonneville to Les Harris, a maker of spare parts for British bikes in the flourishing classic scene.

It was a bold move for Harris to attempt the task that had first broken Triumph itself, and then the workers' co-operative: manufacturing the Triumph Twin at a profit. But his plan was to forget about taking over the huge Meriden site, with its aging machinery and massive overhead costs, and adopt small-is-beautiful thinking. Thus, he has the Bonneville's engine castings machined bv outside suppliers on modern, computer-controlled millers, and uses his factory at Newton Abbot, in southwestern England, only as an assembly plant.

At the time this article was written, a total workforce of a dozen people was producing 16 Bonnevilles a week. This figure is microscopic by the standards of BMW, Harley-Davidson, Cagiva and Moto Guzzi. let alone the Japanese factories. Yet this attempt to keep British bikes in production has aroused worldwide interest in the Bonneville that has so far remained unsatisfied. Although plans for exporting bikes to the United States—once Triumph's largest overseas market—were halted because of the spectre of liability lawsuits, Harris has so many orders from Europe, Japan. Australia and thirdworld countries that he can't even spare road-test machines from his limited output.

With the aid of a Triumph dealer, Terry Hobbs in Plymouth, Devon, I was able to get around the availability problem and subject a new' Bonneville to a full l 000-mile evaluation and performance-testing session. I treated the bike as a modern motorcycle and made no allowances for its dated basic concept beyond the one consideration that should be extended to every road-test machine: use it for what it was designed to do. The Bonneville’s makers don't claim that it competes in terms of speed and power with Japanese bikes, so it would be unjust and unrealistic to expect tire-smoking acceleration or turbine-smooth cruising at l 00 mph.

So w hat is it like to ride, this inheritor of nearly 40 years of Triumph tradition?

In a word, odd. For one thing, you have to kickstart the engine into life. Made-at-Meriden Bonnevilles could be bought with an electric starter, but Les Harris decided that Real Motorcyclists can live without the cost and complexity of this soft option. And in a way, he's right. With a mild, 7.9:1 compression ratio, the Triumph isn't difficult to swing into life. On a cold morning, w hen the engine oil is thick, you might lunge at the long lever half a dozen times before the machine erupts into that characteristic soft thunder of a parallel Twin. But once the engine is warm, starting is a oneor two-prod affair.

Also odd for anyone unpracticed in the ways of the parallel Twin is w hat happens if. with the engine running and the bike on its centerstand, you blip the throttle: Vibration makes the Bonneville shuffle hackwards across your garage floor. But when you roll the machine off the stand and take its bulk in your hands, you feel two of the advantages of British Twins—light weight and a low center of gravity. The Bonneville’s makers claim that its dry weight is only 395 pounds, but they're optimistic: with oil and half a tank of fuel, the test bike weighed 440 pounds, so its dry weight is probably around 420 pounds. Even so, that's favorable in comparison to most four-cylinder 750s.

When you pull away on the Bonneville. you learn of another characteristic of parallel Twins: their soft, creamy lowand mid-range torque. Clutch slip from a standstill is barely necessary, and the bike will accelerate in fifth gear from as low as 25 mph. But from 5000 rpm to the 7000-rpm redline, vibration intrudes, and the mechanically sympathetic owner will want to ease back on the throttle.

Physical discomfort resulting from vibration is not actually a major problem on the '86 Bonneville. The handlebar and footrests are rubbermounted, and the seat is deep and plush. The B o n n e v i lie w ou ld be more comfortable yet were it not for the position of the footpegs. which were moved forward 10 years ago when the foot controls were flipflopped to comply with U.S. regùlations.

Assisted by a strong tailwind, the test bike recorded a best one-way speed of 1 1 5 mph, with the engine spinning at 7200 rpm. Its two-way average was 1 1 1 mph —feeble by the standards of Japanese 750s, but strong running for a 50-horsepower Twin increasingly muzzled by noise legislation. The Bonneville’s silencers, made by Franconi of Italy, do a good job of keeping the exhaust note remarkably quiet without smothering the engine.

Other Italian fittings include some of the machine's best features; the Paioli front fork and twin rear dampers, and the Brembo disc brakes. The front end is quite softly sprung, and when the considerable power of the Brembos is used, fork plunge is almost of BMW proportions. But the choice of springing and damping rates is no doubt correct for the Bonneville buyer of the Eighties. For the same reason, ground clearance is also adequate for most riders, although those accustomed to Japanese sportbikes will probably complain that the centerstand scrapes too easily on the left side.

Like most other equipment on the Bonneville, the suspension components have been kept simple. The fork lacks air assistance and antidive, and there are no multiple adjustment facilities front or rear. The only adjustment the rear shocks offer is spring preload, and that by a mere three settings. But the fittings seem adequate for a machine of this weight and performance, as does the decidedly old-fashioned 19-inch front wheel. The bike has a pleasantly neutral steering response, and handling and stability are assisted by a massive frame, which has twin engine-cradle tubes at the front and a large-diameter, oil-carrying backbone.

Other equipment is a mixture of old and new. Ignition is via a British Rita Mistral electronic system, while the instruments come from Veglia of France and the switchgear and handlebar controls from Magura in Germany—in all, a reflection of the decline of Britain's motorcycle component industry. But the Avon Roadrunner tires are made in England, and cope easily with the Bonneville's performance.

Faults on the machine include an irritating carburetion stutter when the throttle is opened suddenly at 3500-4000 rpm. This was a feature of Meriden-built Triumphs, and it should have been cured by now. Oil consumption on the test bike went as high as one pint every 250 miles during prolonged freeway cruising at 7080 mph, which seems abnormally high, even by old Bonneville standards. In addition, making clean gearchanges with the short shift lever calls for determined boot pressure; and the neutral light often illuminates when the machine is in second gear, which can result in stalls in traffic. There is no electric assistance to re-light the fire, remember?

But most riders will find the Triumph a friendly tool nonetheless. In Britain, its basic specification and inexpensive spares prices—often half the cost of comparable components for Japanese machines—are popular with owners who like to handle their own maintenance chores and run a bike that is readily rebuildable.

In the Fifties and Sixties, British factories staked their futures on parallel Twins. BSA, Norton, Triumph, Royal Enfield, AJS, Matchless and Ariel all built them. In the long term, it was a bad gamble: There are better engine layouts for motorcycles, as other countries' manufacturers have proved. But now the Bonneville is the sole-surviving British Twin, a bike that refused to die; and its very uniqueness seems likely to keep it in production for some years to come, especially since it is now' better made and better equipped than ever before.

Just don't expect it to compete in the fast lane anymore.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

October 1986 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

October 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the Ten Best

October 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

October 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

October 1986 By Alan Cathcart