BROUGH SUPERIOR

Performance that stands the test of time

MIKE NICKS

IN HIS 20 YEARS AS A MANUfacturer of motorcycles, George Brough sold only 3000 machines; he was hardly the pre-war equivalent of Soichiro Honda. But Brough was not concerned with quantity. He built exclusive products for aristocrats of speed who thought nothing of packing 700 miles a day on the empty roads of the 1920s and ’30s.

A typical Brough Superior was the 1928 lOOOcc Pendalpine, even though only about three of this particular model are believed to have been made. The Pendalpine was a cross between Brough’s Pendine Racer and his Alpine Grand Sports Luxury Tourer. It was fitted with an overhead-valve V-Twin motor made by the famous JAP engine company in North London, and civilized for the road by the addition of a kickstarter and fenders.

It also came with a guarantee that it would do 1 10 mph. Sixty

years ago, that was an astonishing speed for a road-legal motorcycle. For one thing, it was 90 mph faster than the maximum speed limit on all of Britain’s highways, not just the urban roads. And it was only 20 mph slower than the highest speed that had then been attained on a motorcycle in Europe—that being the 130 mph recorded in France by British rider Freddie Dixon in 1927, on a Brough.

The Pendalpine was a typically flamboyant gesture by George Brough. His most famous and popular models were the lOOOcc side-valve SS80 V-Twin launched in 1923, and the SS 100 overheadvalve version that followed a year later. He also built an extraordinary series of prototypes and show bikes that even he could barely have expected to sell widely.

These creations included a sort of forerunner of the Honda Gold Wing, the Brough Superior Dream of 1938. Like the Wing, the Dream was a lOOOcc flat-Four

with shaft drive. Unlike the Wing, however, it was air-cooled rather than liquid-cooled. But Brough sidestepped any possibility of overheating in his engine by placing one cylinder atop the other on each side of the crankcase, and using two geared-together crankshafts. World War II prevented Brough from finding out whether the motorcycling public wanted, or would be willing to pay for, his ultimate superbike.

Other Brough extravagances were a lOOOcc V-Four in 1927; a 900cc straight Four, with the cylinders in line with the frame rather than mounted across it, in 1928; and in 1931, an unusual threewheeler powered by an 800cc version of the famous Austin Seven car engine. This Brough was intended strictly for sidecar work, which explains its use of dual rear wheels and a reverse gear. It even retained the car’s electric starting in an era when most motorcycles were working men’s transport built to stringent price levels.

The Brough became known as the “The Rolls-Royce of motorcycles” after the phrase had been used in a magazine test of an SS80; even the makers of the legendary Rolls permitted George Brough to repeat this encomium. Yet the fact was that Brough was more of an assembler of other people’s parts than he was a fully independent manufacturer.

As well as JAP and Austin engines, Brough relied on power

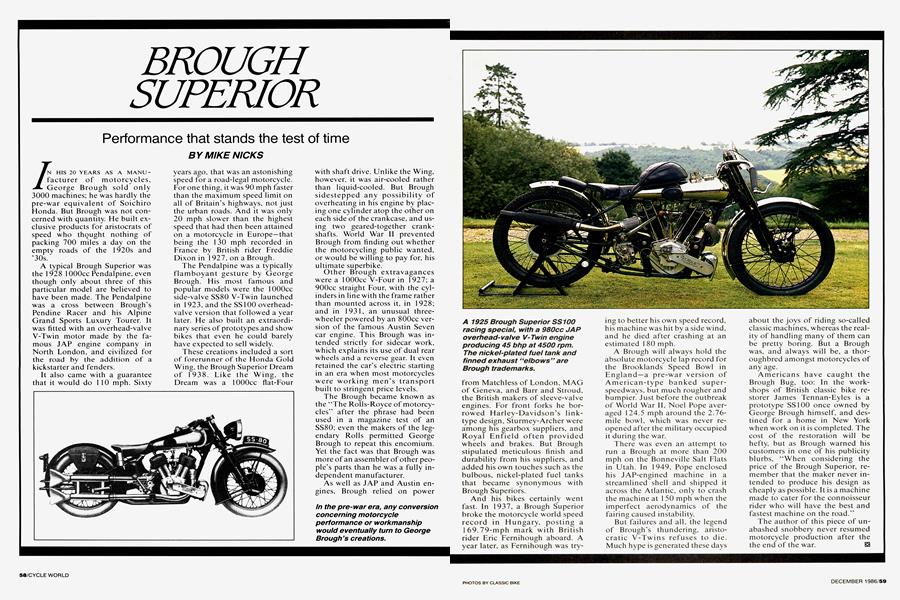

from Matchless of London, MAG of Geneva, and Barr and Stroud, the British makers of sleeve-valve engines. For front forks he borrowed Harley-Davidson’s linktype design, Sturmey-Archer were among his gearbox suppliers, and Royal Enfield often provided wheels and brakes. But Brough stipulated meticulous finish and durability from his suppliers, and added his own touches such as the bulbous, nickel-plated fuel tanks that became synonymous with Brough Superiors.

And his bikes certainly went fast. In 1937, a Brough Superior broke the motorcycle world speed record in Hungary, posting a 169.79-mph mark with British rider Eric Fernihough aboard. A year later, as Fernihough was try-

ing to better his own speed record, his machine was hit by a side wind, and he died after crashing at an estimated l 80 mph.

A Brough will always hold the absolute motorcycle lap record for the Brooklands Speed Bowl in England —a pre-war version of American-type banked superspeedways, but much rougher and bumpier. Just before the outbreak of World War II, Noel Pope averaged 124.5 mph around the 2.76mile bowl, which was never reopened after the military occupied it during the war.

There was even an attempt to run a Brough at more than 200 mph on the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. In 1949, Pope enclosed his JAP-engined machine in a streamlined shell and shipped it across the Atlantic, only to crash the machine at l 50 mph when the imperfect aerodynamics of the fairing caused instability.

But failures and all, the legend of Brough’s thundering, aristocratic V-Twins refuses to die. Much hype is generated these days

about the joys of riding so-called classic machines, whereas the reality of handling many of them can be pretty boring. But a Brough was, and always will be, a thoroughbred amongst motorcycles of any age.

Americans have caught the Brough Bug, too: In the workshops of British classic bike restorer James Tennan-Eyles is a prototype SSI00 once owned by George Brough himself, and destined for a home in New York when work on it is completed. The cost of the restoration will be hefty, but as Brough warned his customers in one of his publicity blurbs, “When considering the price of the Brough Superior, remember that the maker never intended to produce his design as cheaply as possible. It is a machine made to cater for the connoisseur rider who will have the best and fastest machine on the road.”

The author of this piece of unabashed snobbery never resumed motorcycle production after the the end of the war. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

December 1986 By Paul Dean -

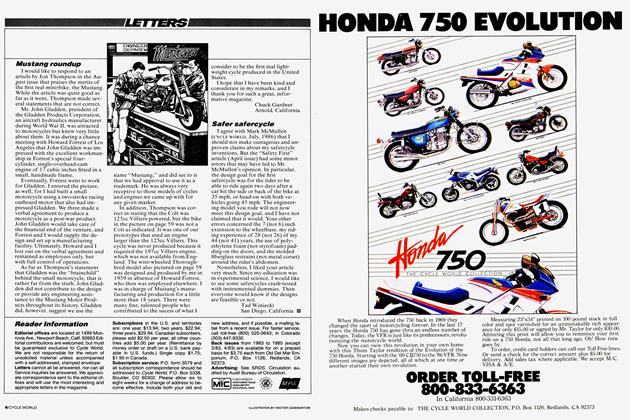

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1986 -

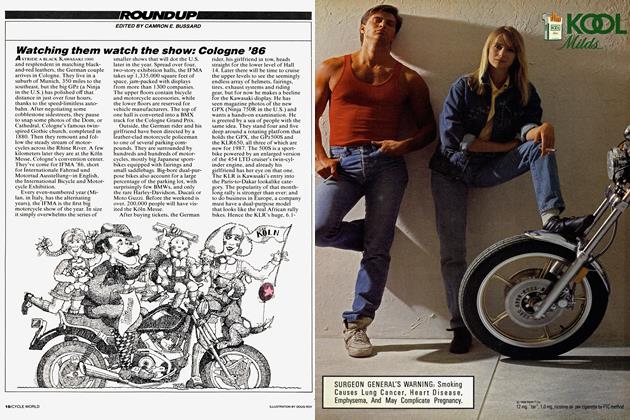

Roundup

RoundupWatching Them Watch the Show: Cologne '86

December 1986 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

December 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

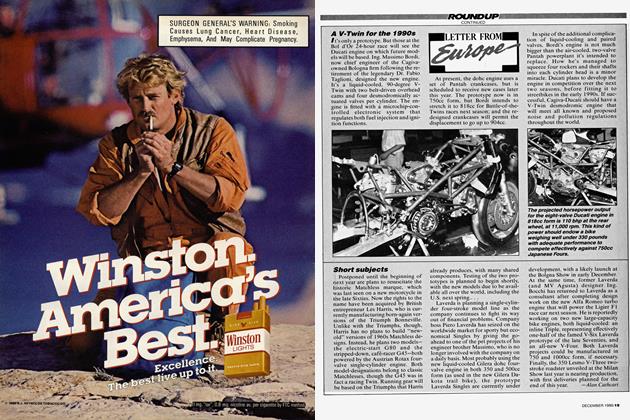

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

December 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

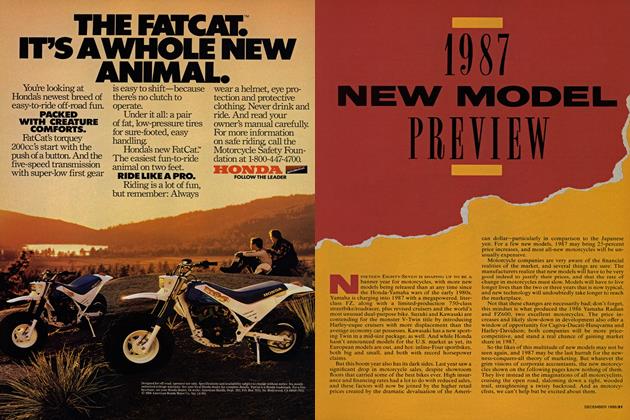

1987 Previews And Riding Impressions

1987 Previews And Riding Impressions1987 New Model Preview

December 1986