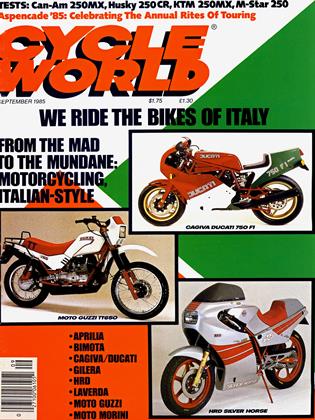

THE MOTORCYCLES OF ITALY

DAVID EDWARDS

STEVE ANDERSON

Proof positive that the land of Michelangelo and DaVinci is still sculpting works of art

ITALY IS A COUNTRY DRIVEN BY PASsion. It is a country that revels in the beauty of its women as if they were a national treasure. It is a country where good food and fine wine are things to be remembered for a lifetime. It is a country that will say no to the building of a factory rather than spoil the view of a crumbling, 500-year-old castle. It is a country that has spawned some of the most important artists, composers and designers of all time. And it is a country caught happily in the throes of a torrid love affair with motorcycling.

For evidence, just visit any good-sized Italian town on a summer afternoon. Around the square in the center of town, the teenagers invariably huddle, clusters of them, talking about school, the latest fashions in clothes, the outcome of last night’s soccer game. And always there are motorcycles, scooters or mopeds nearby. In America, every 1 6-year-old’s wish may still be for a new Camaro Z28, but the realities of the flailing Italian economy mean that many of the teenagers there—girls as well as boys— will have some kind of two-wheeler as their first motorized vehicle. Even courtship is accomplished on two wheels, as young lovers, sitting impossibly close, head out of town for a few uninterrupted hours at the lake, a blanket and lunch on the rear of the motorcycle.

Not that the Italians’ love for motorcycling ends with puberty. On the streets that ring the central shopping district in most cities, earnest-looking housewives astride windshield-equipped mopeds ply their way from one shop to another, packing away supplies for Sunday’s after-church dinner. And old men, somehow stately on their aging, sun-bleached scooters, pass regally through the traffic, making for their favorite sidewalk café and a game of checkers washed down with a glass of grappe.

In the rain-drenched hills above the city, members of the local motorcycle club wring out their sportbikes along tightly twisting, tree-lined roads as they take the long route to Sunday's roadrace grand prix that will draw 50,000 fellow enthusiasts. Other riders, intent on making it to the racetrack in time to watch Saturday’s practice sessions, fly along the freeway, or autostrada, at 80 or 90 miles per hour in a loose nose-to-tail formation, unworried about getting speeding tickets, but keeping a watch out for the occasional Mercedes or Ferrari that may come busting through at 1 20 miles an hour.

All in all, there's more motorcycle activity going on in and around the typical Italian city on one Saturday afternoon than a similar-sized American town sees in a month.

There are several reasons why Italians are so headover-heels crazy about motorcycles. Certainly the economy is one very big reason. The average Italian worker brings home only about $6000 a year, which makes it easy to understand why mopeds, scooters and small motorcycles—with their low purchase prices, high mileage and affordable insurance rates—have such a following over there. Then too, there is tradition. After World War II, there weren’t many cars available for personal transportation in battle-scarred Italy, and the easiest and cheapest way to get the country moving again was on two wheels.

Still, it’s likely that the main reason Italy is so in love with motorcycles has nothing to do with purchase price or fuel economy or anything else quite so logical. Ask an Italian why he likes motorcycles so fervently and the answer will come back quickly and unashamedly: “Motorcycles? They are my passion." >

But while we in the U.S. often think of the consummate Italian motorcycle as a big-engined sportbike wrapped in a tight-waisted frame, the bikes that are fueling the Italians’ passions these days are, in fact, at the opposite end of the motorcycle spectrum. By far the most popular machines in Italy right now are dualpurpose bikes, street-legal, dirt-styled machines referred to as “enduros.”

This discovery might explode America’s long-held assumption that all Italian motorcyclists scurry about on roadrace-replicas with visions of Giacomo Agostini dancing in their heads. That might have been true some years ago, but no more. Today’s typical Italian motorcyclist rides a replica of a European-style enduro racer, and you can blame that craze on the Paris-Dakar off-road rally and the various offspring that wildly popular event has fostered. Italian motorcycle analysts say that for now, enduros are “in style’’ and “the fashion,” although some predict that other styles, including the Americaninfluenced custom-bike look, may soon come into vogue.

Styling trend or not, dual-purpose bikes make perfect sense in Italy, where roads are often in poor repair and long-travel, motocross-type suspension is a definite boon. Also, an enduro bike’s upright seating position, light weight and easy maneuverability come in very handy in the motorized free-fire zones that Italians know as crosstown commuting. And when the time comes for attacking the hairpin-laced roads that wind up and down the sides of the mountains of northern Italy, there’s no better ally than a dual-purpose bike.

That’s why to do business in Italy in the Eighties, a company needs a rally-styled enduro bike. And even firms that previously catered to allstreet audiences are selling dual-purpose bikes, with some going as far as making plans to enter a real dirt bike in the Paris-Dakar Rally, just to have some fodder for the intense advertising wars that are waged after that 2 1 -day competition is concluded.

In Italy it’s important to have even the slightest advantage when it comes to advertising, because at any given moment there are something like 20 different companies producing mopeds, scooters or motorcycles. This, at a time when America has but one remaining motorcycle company, when once-all-powerful England has been reduced to a cottage industry turning out one-offs and specials, when Spain’s glory days are just a footnote in motorcycling’s encyclopedia, and when West Germany soldiers along with no more than a solitary streetbike manufacturer.

Don't think this state of affairs happened through some strange quirk of circumstance, however. Years ago, the Italians saw what the onslaught of the efficient Japanese steamroller could do. and in a characteristic display of red-white-andgreen flag waving, banned the importation of any bike smaller than 380cc.

While that import ban gave the Italian manufacturers some muchneeded protection, other laws made sure the small-displacement market was strong. Licensing regulations, for instance, stipulate that between the ages of 14 and 16, Italians can legally operate mopeds—a moped being defined as a motorized twoor threewheeler, with or without pedals, making 1.5 horsepower and with a top speed of 40 kilometers per hour (25 mph) or less. At age 16, they can move up to a 125cc motorcycle, which explains why this is currently the best-selling motorcycle class in Italy by far. Between the ages of 1 8 and 21, 350cc is the limit, and after 21, any displacement is fair game.

Besides boosting under-380cc sales, the licensing laws have yielded an additional benefit. Despite the fact that there is no riding examination when applying for a motorcycle license in Italy, that country has a far lower accident and mortality rate for motorcycles than does any other country in Europe.

Another step the government has taken to bolster small-bike sales is to assess bikes under 380cc an 18-percent sales tax. And while this is stiff enough, it’s nowhere near as oppressive as the 38-percent tax levied against larger-displacement bikes. It’s not hard to see, then, why small bikes are so popular in Italy.

Neither is it all that difficult to become a manufacturer and go after your own slice of that small-bike pie. Most manufacturers in Italy, you see, are little more than motorcycle assembly companies. All an aspiring motorcycle manufacturer must do to get into business is design a basic motorcycle that he thinks will sell. Next, he gets on the phone and starts cutting deals with suppliers. Finding a small-displacement two-stroke engine to power the bike is no promblem. A frame-building shop in Bologna, say, will be glad to weld up a batch of frames and swingarms. Another shop will supply the fuel tank, someone else the plastic components. A call to Marzocchi, and forks and shocks are soon on their way.

Dell’Orto has carburetors, Pirelli has tires. C.E.V. has instruments and controls, Brembo has brakes. Once all the details are worked out and delivery dates set, he rents some warehouse space, hires some workers, places a few ads, and presto, he’s a low-volume motorcycle manufacturer. That approach is used even by some of the large Italian manufacturers, except that they usually build their own engines.

Don’t get the idea, though, that all is sunshine and roses in the Italian motorcycle industry. Even with its built-in government protection and a bike-loving population, Italy has not been immune to the worldwide recession in the motorcycle market. Sales have been in a downward spiral since the early 1980s, and this year the worst Italian winter anyone can remember put an icy damper on spring sales and a hoped-for 1985 recovery. Several companies have been forced out of business, and some of those remaining are in what the Italians call amministrazione controllata, a mild version of the Chapter 1 1 bankruptcy code here in the U.S.

To add insult to injury, the Japanese are making inroads into Italy, looking for an increased share of the 200,000-plus motorcycles that are sold there each year. Honda is getting around the import ban with its Honda Italia, an assembly company that bolts together Japanese-designed bikes that use just enough Italian components to qualify as domestic motorcycles. Yamaha is reportedly following suit. And Yamaha had to be encouraged with a recent readers’ poll taken in an Italian magazine which named the XT600 Ténéré, a Paris-Dakar-styled enduro, as the most desired bike in Italy.

Still, the mood is definitely upbeat in Italy. Production lines are becoming more automated, quality is up, designs —both technical and aesthetic—are fresh, and there are some truly landmark Italian motorcycles just around the bend.

In the following pages, Cycle World takes a closer look at eight of the most important Italian motorcycle companies and their products. Some have familiar names; others do not but will be seen in the U.S. in the next year or two; and still others are destined never to touch rubber on American roads. Whatever their fate, though, the companies and motorcycles that follow all display that unmistakable characteristic that marks them as uniquely Italian.

They all display passion.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

September 1985 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

September 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupAikido: Pre-Accident Preparation

September 1985 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

September 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

September 1985 By Alan Cathcart