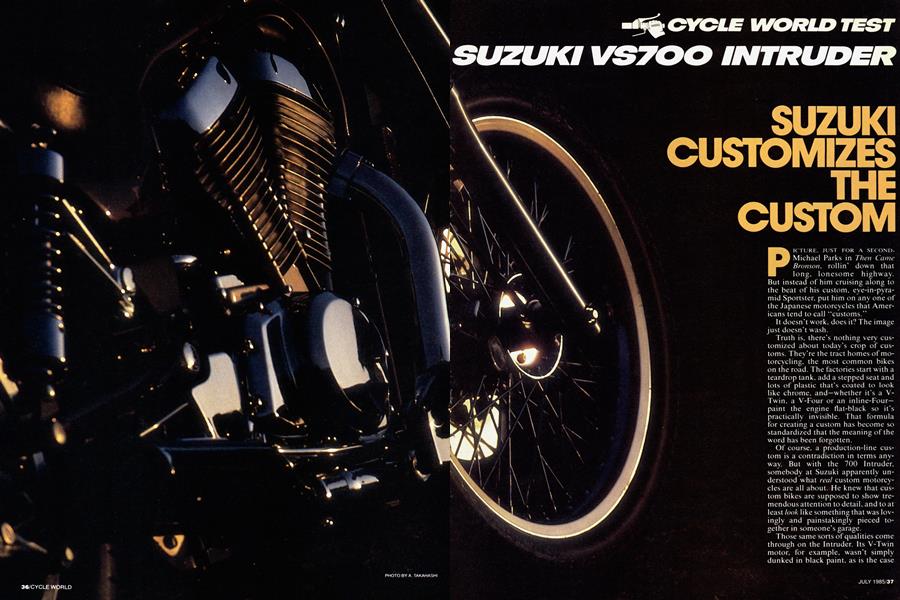

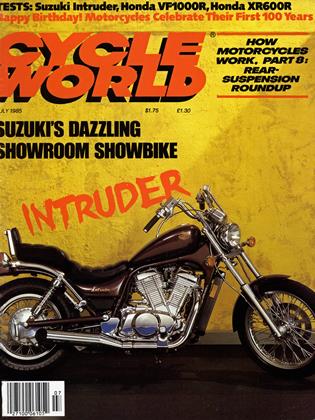

SUZUKI CUSTOMIZES THE CUSTOM

CYCLE WORLD TEST

SUZUKI VS700 INTRUDER

PICTURE. JUST FOR A SECOND. Michael Parks in Then Came Bronson. rollin' down that long, lonesome highway. But instead of him cruising along to the beat of his custom, eye-in-pyramid Sportster, put him on any one of the Japanese motorcycles that Americans tend to call “customs.”

It doesn't work, does it? The image just doesn't wash.

Truth is. there's nothing very customized about today's crop of customs. They’re the tract homes of motorcycling, the most common bikes on the road. The factories start w ith a teardrop tank, add a stepped seat and lots of plastic that's coated to look like chrome, and—whether it's a VTwin. a V-Four or an inline-Four— paint the engine flat-black so it's practically invisible. That formula for creating a custom has become so standardized that the meaning of the word has been forgotten.

Of course, a production-line custom is a contradiction in terms anyway. But with the 700 Intruder, somebody at Suzuki apparently understood what real custom motorcycles are all about. He knew that custom bikes are supposed to show tremendous attention to detail, and to at least look like something that was lovingly and painstakingly pieced together in someone’s garage.

Those same sorts of qualities come through on the Intruder. Its V-Twin motor, for example, wasn’t simply dunked in black paint, as is the case with most other Japanese cruisers. It glints of real metal, with honest-togod chrome-plating on the engine cases and valve covers. Only the engine center cases and cylinders are painted, and even that paint is a fairly high-gloss aluminum coating, far from the all-too-usual flat-black.

The rest of the Intruder looks like a rolling billboard for a chrome factory. Everywhere you look, there’s more chrome, from the triple-clamps right down to the fuel petcock. Even the 60 spokes in each of the wirespoked wheels are chromed. And what isn't chrome-plated is either polished or painted to match the fuel tank. The clutch and front-brake master cylinders are aluminum with a brushed finish, as are the housings for the control switches and the twistgrip. And what little plastic there is on the Intruder has been effectively hidden; items such as its two separate seat bases and dual airboxes are not in plain view.

So without question, the Intruder has the flashiest finish of any motorcycle Japan has ever manufactured. But Suzuki’s goal with this bike was to have more than a shiny facade, more than just a Universal Japanese Motorcycle dipped in chrome. Rather, the Intruder was intended to break out of the traditional Japanesebike mold. And it succeeds. One way is in its size, for the Intruder is a dwarf in a world of giants. It has a lower seat than any bike in its class, and its VTwin engine is narrower than any other current Twin.

That's no accident. When Suzuki took to the drawing boards to design its new V-Twin, the goals were very specific. And making the engine small and light was right at the top of the list. So at its widest point, the Intruder's 699cc V-Twin engine measures only about 1 5 inches across. To put that number in perspective, a Harley-Davidson Sportster V-Twin engine is around 1 8 inches wide, and a Yamaha XT600 Single is about 14 inches across. Having such a narrow engine also meant that the chassis had to be extraordinarily thin. That left little room under the seat, so the designers wound up putting certain components in some unusual locations—such as the battery, which is under the swingarm, just inches off the ground.

Within that narrow engine, you'll find most of the modern technology that is typical of current Japanese motorcycles. Like liquid-cooling, for example. But because Suzuki was going for the traditional look with this motorcycle, the engine was given enough finning to look air-cooled. And whereas glitter and chrome can be found on almost every other part of the motorcycle, the unusually narrow radiator is painted black and is all but unnoticeable on the frame’s front downtubes.

Other examples of styling concealing technology can be found in the top end. Each of the Intruder’s cylinders has a single overhead cam op-

erating four valves through forked cam followers; but Suzuki deliberately styled the tops of the cylinder heads so they look more like rocker boxes on a pushrod-style overheadvalve engine. And the Intruder is fitted with two different CV carburetors—a sidedraft carb on the rear cylinder and a downdraft on the front—so they can be hidden away where they won't obstruct the view of the engine’s 45-degree V-spread.

Although a 45-degree V-Twin offers less-than-perfect primary balance, the Intruder uses no counterbalancers. It does, however, have

staggered crankpins much like those used in the Honda Shadows. But Suzuki staggers the pins 45 degrees, rather than 90 degrees as Honda has on the 700 Shadow. And unlike Honda, Suzuki makes no claims that this stagger results in perfect primary balance, only that it makes the engine a little smoother than one with no stagger, the crankshaft a little stronger than one with 90 degrees of stagger, and the exhaust note a lot more pleasing than either one.

But even though the engine is far from dead-smooth, the pulsations it transmits to the handlebar and footpegs are far from the buzzy tingling given off by a Shadow 700. The Intruder just has a solid throb that increases in frequency as the rpm climbs. Even on trailing throttle, where a lot of Twins develop a severe case of the shakes, the Suzuki is comparatively smooth. And the engine's sound is distinctly un-Japanese, too, with a rumbly, offbeat exhaust note at idle. It doesn’t really sound much like a Harley, for the beats are too regular and not quite as deep. But then, the Intruder doesn’t produce a sanitized, UJM-like hum, either, at least not until the motor is wound up into the higher rpm ranges. Then the exhaust note sounds more ordinary, almost like that of a multi.

An engine’s primary function isn’t to be heard, though, or even looked at; it’s to make power. And in that area, the Intruder unceremoniously falls into the middle of the pack. VTwins are famous for low-rpm torque and broad powerbands, and, predictably, those are this motor’sbest characteristics. So, since all you have to do is roll the throttle open, passing slower traffic is easy and only requires a downshift if you’re in a hurry or don’t have much passing room.

That good roll-on performance is due partly to the Intruder’s low overall gearing and partly due to its low overall weight. Still, the bike isn’t exactly a dynamo of power, and would be soundly thrashed by any modern multi in acceleration. But as far as 700cc V-Twins are concerned, the Intruder can hold its own. In quartermile performance, Honda’s Shadow, Yamaha’s Virago and Kawasaki's Vulcan all are within a few tenths of a second of the Intruder.

Anyway, discussions of quartermile performance are academic, because custom-bike buyers in America are unlikely to be swayed by a tenth of a second one way or the other. They might, however, be critical of the brakes and the suspension on the Intruder. The single front disc stops the bike well enough, but the rear drum brake is weak. And suspensionwise, the Suzuki often seems little better than a real hardtail. The rear end tends to be choppy over little bumps, yet it bottoms-out over big ones. And the front fork can't react quickly enough to deal with sharp, abrupt bumps. Combine those suspension traits with a seat that is thinly padded to achieve ultra-lowness, and you end up with a ride that, while not exactly brutal, discourages long stints in the saddle.

Certainly, the ride could be somewhat better if the Intruder had more wheel travel. But the reason for the bike’s relatively short-legged suspension goes back to one of Suzuki’s primary goals—to build a small, low cruiser. The Intruder’s seat is about as low as any in the business, so even the shortest of riders will have no trouble putting both feet flat on the ground when stopped. And despite being fairly narrow and sparsely padded. the rider’s segment of the seat is surprisingly comfortable.

Likewise, the Intruder’s narrowness offers a pleasant surprise. You would expect any bike that sits as low to the ground as the Intruder does to drag its undercarriage practically every time it goes around a corner. But the bike is so narrow that it can reach a fair degree of lean before the footpegs and their brackets touch down. And while that banking ability doesn’t really make the Intruder any more suited for Sunday-morning canyon racing than most other cruisers on the market, the Suzuki is much better in the turns than its low-slung chassis would have you believe.

Of course, serious assaults on twisty roads were never in the Intruder’s battle plans; nevertheless, Suzuki has another Intruder model that's a bit more suited to soft-core sport riding. It’s called the VS700GLF (the model tested here is the VS700GLP), and the only difference is in its handlebar. The F-model Intruder has a low, flat, drag-style handlebar that puts the rider in a better position than the pullback-bar P-model for semi-spirited cornering. And the footpegs work well with either bar, for they’re far enough forward to provide the requisite laid-back riding position but not enough to make spirited cornering awkward. The low bar puts the rider's wrists at a slightly unnatural angle, though, whereas the higher handlebar places the grips precisely where the rider expects to find them. Consequently, the pullback model is a much better choice for general around-town riding.

Whether the high-bar Intruder is more attractive than the low-bar model is a matter of personal taste. Chances are that people who prefer clean, uncluttered custom bikes will like them both, mostly because that sort of bare-bones philosophy is visible everywhere on the Intruder. Homemade customs don't have wires and hoses and cables running everywhere; neither does the Intruder. Homemade customs don't have fuel gauges and water-temperature gauges and idiot lights all over the dash panel; neither does the Intruder. In fact, the Intruder doesn’t have much of a dash panel at all. Just a speedometer and a few warning lights that you don’t even know are there until they’re lit. The bare minimum.

Suzuki did go a bit too far, however, by not even including a resettable tripmeter. Motorcyclists have long relied on tripmeters to indicate when the gas supply might be getting short, but on the Intruder, you simply go until you hit reserve, then start looking for a gas pump. But as far as a tachometer and all the other usual bells and whistles are concerned, it's amazing how little they’re missed.

You also don't miss out on many stares when you're on an Intruder. People love to gawk at the bike, and to walk around it in admiration and ask questions—the most common of which is, “What is it?"

That’s the kind of bike a custom should be—and exactly what the Intruder was designed to be: a conversation piece, a two-wheeled attention-grabber. Its styling may have forced a few concessions on the performance, but at least the Intruder makes a visual statement that is virtually uncompromised. It demonstrates that a production custom bike truly can be a custom.

SUZUKI

VS700 INTRUDER

$3199

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialSoul-Searching In the Engine Bay

July 1985 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeThe Wrong Bag

July 1985 By Steve Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupMotorcycle Ergonomics: Trouble In the Fitting Room

July 1985 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupThe Ultra-High-Performance Yamaha Fz250 Phazer

July 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupThe Striking Yoshimura F1 And F3 Racers

July 1985