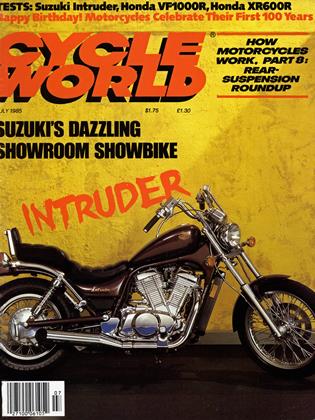

STYLING THE INTRUDER: NOT A CUSTOMARY CUSTOM

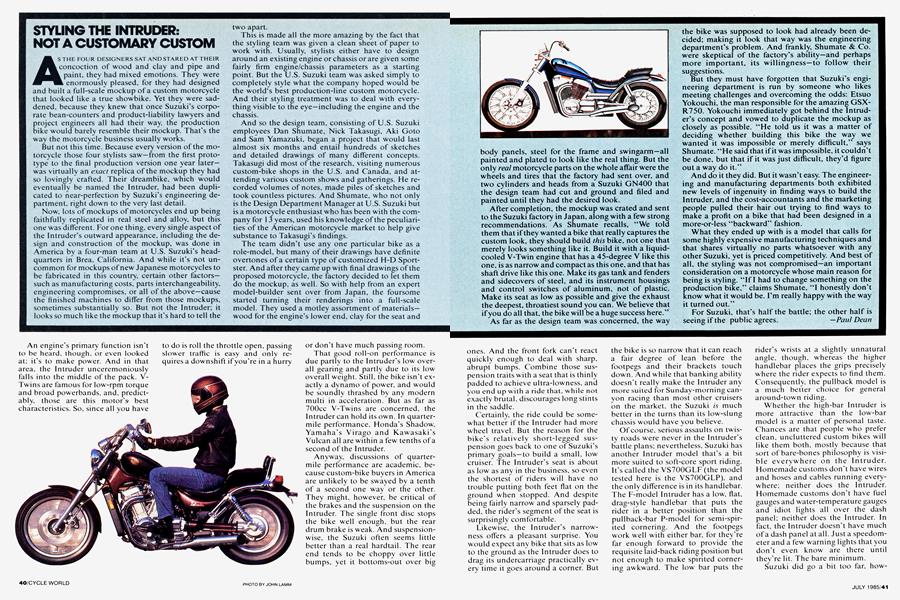

AS THE FOUR DESIGNERS SAT AND STARED AT THEIR concoction of wood and clay and pipe and paint, they had mixed emotions. They were enormously pleased, for they had designed and built a full-scale mockup of a custom motorcycle that looked like a true showbike. Yet they were saddened, because they knew that once Suzuki’s corporate bean-counters and product-liability lawyers and project engineers all had their way, the production bike would barely resemble their mockup. That’s the way the motorcycle business usually works.

But not this time. Because every version of the motorcycle those four stylists saw—from the first prototype to the final production version one year later— was virtually an exact replica of the mockup they had so lovingly crafted. Their dreambike, which would eventually be named the Intruder, had been duplicated to near-perfection by Suzuki’s engineering department, right down to the very last detail.

Now, lots of mockups of motorcycles end up being faithfully replicated in real steel and alloy, but this one was different. For one thing, every single aspect of the Intruder’s outward appearance, including the design and construction of the mockup, was done in America by a four-man team at U.S. Suzuki’s headquarters in Brea, California. And while it’s not uncommon for mockups of new Japanese motorcycles to be fabricated in this country, certain other factors— such as manufacturing costs, parts interchangeability, engineering compromises, or all of the above—cause the finished machines to differ from those mockups, sometimes substantially so. But not the Intruder; it looks so much like the mockup that it’s hard to tell the two apart.

This is made all the more amazing by the fact that the styling team was given a clean sheet of paper to work with. Usually, stylists either have to design around an existing engine or chassis or are given some fairly firm engine/chassis parameters as a starting point. But the U.S. Suzuki team was asked simply to completely style what the company hoped would be the world's best production-line custom motorcycle. And their styling treatment was to deal with everything visible to the eye—including the engine and the chassis.

And so the design team, consisting of U.S. Suzuki employees Dan Shumate, Nick Takasugi, Aki Goto and Sam Yamazuki, began a project that would last almost six months and entail hundreds of sketches and detailed drawings of many different concepts. Takasugi did most of the research, visiting numerous custom-bike shops in the U.S. and Canada, and attending various custom shows and gatherings. He recorded volumes of notes, made piles of sketches and took countless pictures. And Shumate, who not only is the Design Department Managerat U.S. Suzuki but is a motorcycle enthusiast who has been with the company for 13 years, used his knowledge of the peculiarities of the American motorcycle market to help give substance to Takasugi’s findings.

The team didn’t use any one particular bike as a role-model, but many of their drawings have definite overtones of a certain type of customized H-D Sportster. And after they came up with final drawings of the proposed motorcycle, the factory decided to let them do the mockup, as well. So with help from an expert model-builder sent over from Japan, the foursome started turning their renderings into a full-scale model. They used a motley assortment of materials— wood for the engine’s lower end, clay for the seat and body panels, steel for the frame and swingarm—all painted and plated to look like the real thing. But the only real motorcycle parts on the whole affair were the wheels and tires that the factory had sent over, and two cylinders and heads from a Suzuki GN400 that the design team had cut and ground and filed and painted until they had the desired look.

After completion, the mockup was crated and sent to the Suzuki factory in Japan, along with a few strong recommendations. As Shumate recalls, “We told them that if they wanted a bike that really captures the custom look, they should build this bike, not one that merely looks something like it. Build it with a liquidcooled V-Twin engine that has a 45-degree V like this one, is as narrow and compact as this one, and that has shaft drive like this one. Make its gas tank and fenders and sidecovers of steel, and its instrument housings and control switches of aluminum, not of plastic. Make its seat as low as possible and give the exhaust the deepest, throatiest sound you can. We believe that ifyou do all that, the bike will be a huge success here.”

As far as the design team was concerned, the way the bike was supposed to look had already been decided; making it look that way was the engineering department’s problem. And frankly, Shumate & Co. were skeptical of the factory’s ability—and perhaps more important, its willingness—to follow their suggestions.

But they must have forgotten that Suzuki’s engineering department is run by someone who likes meeting challenges and overcoming the odds: Etsuo Yokouchi, the man responsible for the amazing GSXR750. Yokouchi immediately got behind the Intruder’s concept and vowed to duplicate the mockup as closely as possible. “He told us it was a matter of deciding whether building this bike the way we wanted it was impossible or merely difficult,” says Shumate. “He said that if it was impossible, it couldn’t be done, but that if it was just difficult, they’d figure out a way do it.”

And do it they did. But it wasn’t easy. The engineering and manufacturing departments both exhibited new levels of ingenuity in finding ways to build the Intruder, and the cost-accountants and the marketing people pulled their hair out trying to find ways to make a profit on a bike that had been designed in a more-or-less “backward” fashion.

What they ended up with is a model that calls for some highly expensive manufacturing techniques and that shares virtually no parts whatsoever with any other Suzuki, yet is priced competitively. And best of all, the styling was not compromised—an important consideration on a motorcycle whose main reason for being is styling. “If I had to change something on the production bike,” claims Shumate, “I honestly don’t know what it would be. I’m really happy with the way it turned out.”

For Suzuki, that's half the battle; the other half is seeing if the public agrees. —Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialSoul-Searching In the Engine Bay

July 1985 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeThe Wrong Bag

July 1985 By Steve Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupMotorcycle Ergonomics: Trouble In the Fitting Room

July 1985 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupThe Ultra-High-Performance Yamaha Fz250 Phazer

July 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupThe Striking Yoshimura F1 And F3 Racers

July 1985