The ties that bind usually

EDITORIAL

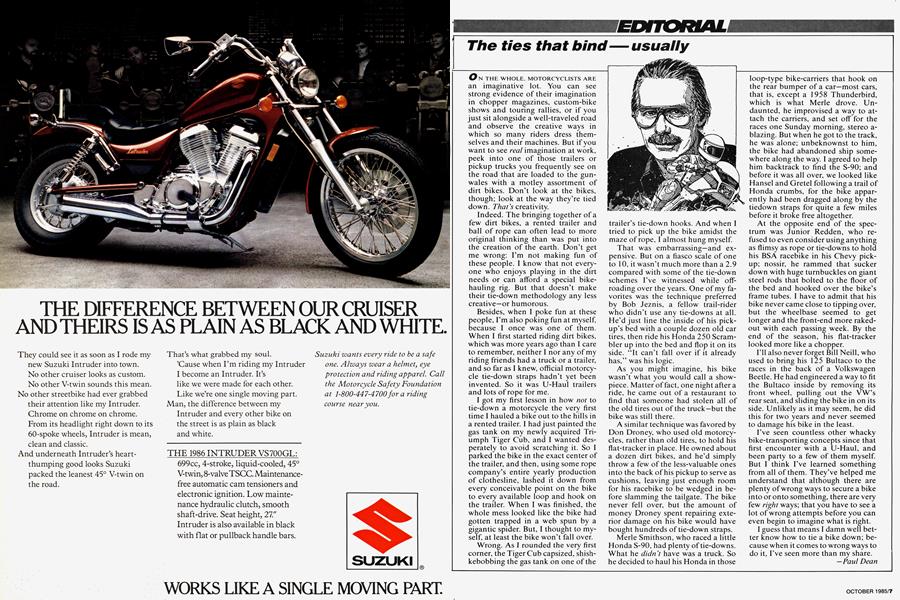

ON THE WHOLE, MOTORCYCLISTS ARE an imaginative lot. You can see strong evidence of their imagination in chopper magazines, custom-bike shows and touring rallies, or if you just sit alongside a well-traveled road and observe the creative ways in which so many riders dress themselves and their machines. But if you want to see real imagination at work, peek into one of those trailers or pickup trucks you frequently see on the road that are loaded to the gunwales with a motley assortment of dirt bikes. Don’t look at the bikes, though; look at the way they’re tied down. That's creativity.

Indeed. The bringing together of a few dirt bikes, a rented trailer and ball of rope can often lead to more original thinking than was put into the creation of the earth. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not making fun of these people. I know that not everyone who enjoys playing in the dirt needs or can afford a special bikehauling rig. But that doesn’t make their tie-down methodology any less creative—or humorous.

Besides, when I poke fun at these people, I’m also poking fun at myself, because I once was one of them. When I first started riding dirt bikes, which was more years ago than I care to remember, neither I nor any of my riding friends had a truck or a trailer, and so far as I knew, official motorcycle tie-down straps hadn’t yet been invented. So it was U-Haul trailers and lots of rope for me.

I got my first lesson in how not to tie-down a motorcycle the very first time I hauled a bike out to the hills in a rented trailer. I had just painted the gas tank on my newly acquired Triumph Tiger Cub, and I wanted desperately to avoid scratching it. So I parked the bike in the exact center of the trailer, and then, using some rope company’s entire yearly production of clothesline, lashed it down from every conceivable point on the bike to every available loop and hook on the trailer. When I was finished, the whole mess looked like the bike had gotten trapped in a web spun by a gigantic spider. But, I thought to myself, at least the bike won’t fall over.

Wrong. As I rounded the very first corner, the Tiger Cub capsized, shishkebobbing the gas tank on one of the trailer’s tie-down hooks. And when I tried to pick up the bike amidst the maze of rope, I almost hung myself.

That was embarrassing—and expensive. But on a fiasco scale of one to 10, it wasn’t much more than a 2.9 compared with some of the tie-down schemes I’ve witnessed while offroading over the years. One of my favorites was the technique preferred by Bob Jeznis, a fellow trail-rider who didn’t use any tie-downs at all. He’d just line the inside of his pickup’s bed with a couple dozen old car tires, then ride his Honda 250 Scrambler up into the bed and flop it on its side. “It can’t fall over if it already has,’’ was his logic.

As you might imagine, his bike wasn’t what you would call a showpiece. Matter of fact, one night after a ride, he came out of a restaurant to find that someone had stolen all of the old tires out of the truck—but the bike was still there.

A similar technique was favored by Don Droney, who used old motorcycles, rather than old tires, to hold his flat-tracker in place. He owned about a dozen dirt bikes, and he’d simply throw a few of the less-valuable ones into the back of his pickup to serve as cushions, leaving just enough room for his racebike to be wedged in before slamming the tailgate. The bike never fell over, but the amount of money Droney spent repairing exterior damage on his bike would have bought hundreds of tie-down straps.

Merle Smithson, who raced a little Honda S-90, had plenty of tie-downs. What he didn't have was a truck. So he decided to haul his Honda in those loop-type bike-carriers that hook on the rear bumper of a car—most cars, that is, except a 1958 Thunderbird, which is what Merle drove. Undaunted, he improvised a way to attach the carriers, and set off for the races one Sunday morning, stereo ablazing. But when he got to the track, he was alone; unbeknownst to him, the bike had abandoned ship somewhere along the way. I agreed to help him backtrack to find the S-90; and before it was all over, we looked like Hansel and Gretel following a trail of Honda crumbs, for the bike apparently had been dragged along by the tiedown straps for quite a few miles before it broke free altogether.

At the opposite end of the spectrum was Junior Redden, who refused to even consider using anything as flimsy as rope or tie-downs to hold his BSA racebike in his Chevy pickup; nossir, he rammed that sucker down with huge turnbuckles on giant steel rods that bolted to the floor of the bed and hooked over the bike’s frame tubes. I have to admit that his bike never came close to tipping over, but the wheelbase seemed to get longer and the front-end more rakedout with each passing week. By the end of the season, his flat-tracker looked more like a chopper.

I’ll also never forget Bill Neill, who used to bring his 125 Bultaco to the races in the back of a Volkswagen Beetle. He had engineered a way to fit the Bultaco inside by removing its front wheel, pulling out the VW’s rear seat, and sliding the bike in on its side. Unlikely as it may seem, he did this for two years and never seemed to damage his bike in the least.

I’ve seen countless other whacky bike-transporting concepts since that first encounter with a U-Haul, and been party to a few of them myself. But I think I’ve learned something from all of them. They’ve helped me understand that although there are plenty of wrong ways to secure a bike into or onto something, there are very few right ways; that you have to see a lot of wrong attempts before you can even begin to imagine what is right.

I guess that means I damn well better know how to tie a bike down; because when it comes to wrong ways to do it, I’ve seen more than my share.

Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

At LargeFighting Back

October 1985 By Steve Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupForecasting Another Good Year

October 1985 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

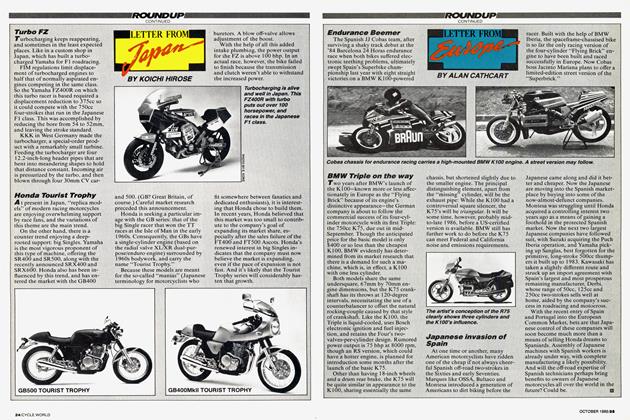

RoundupLetter From Japan

October 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

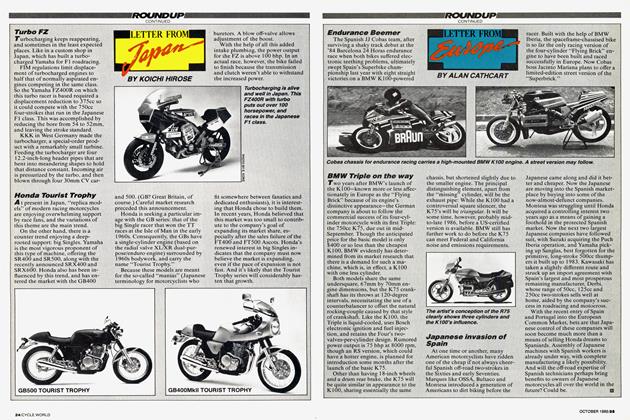

RoundupLetter From Europe

October 1985 By Alan Cathcart -

Feature

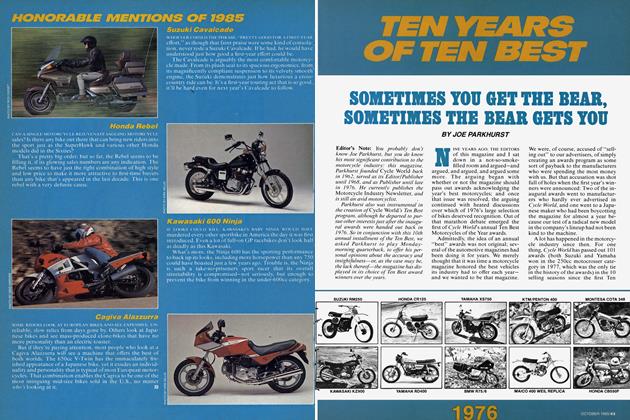

FeatureTen Years of Ten Best

October 1985 By Joe Parkhurst