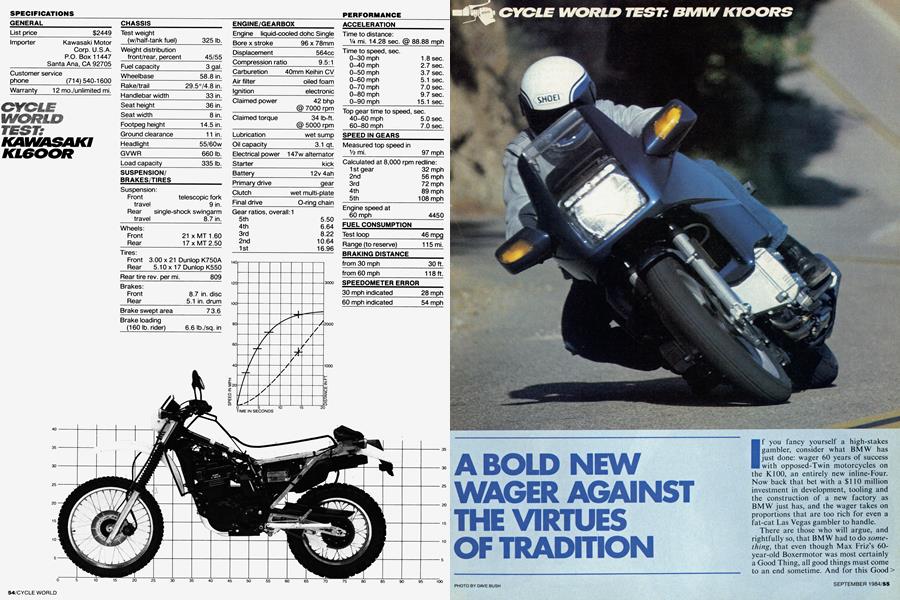

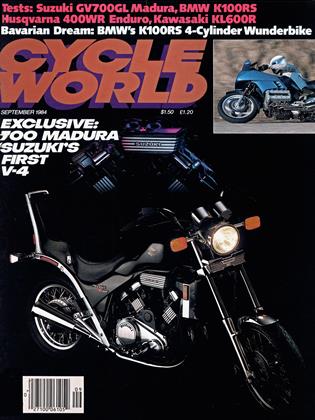

BMW K100RS

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A BOLD NEW WAGER AGAINST THE VIRTUES OF TRADITION

If you fancy yourself a high-stakes gambler, consider what BMW has just done: wager 60 years of success with opposed-Twin motorcycles on the K100, an entirely new inline-Four. Now back that bet with a $110 million investment in development, tooling and the construction of a new factory as BMW just has, and the wager takes on proportions that are too rich for even a fat-cat Las Vegas gambler to handle.

There are those who will argue, and rightfully so, that BMW had to do something, that even though Max Friz’s 60year-old Boxermotor was most certainly a Good Thing, all good things must come to an end sometime. And for this Good> Thing, that sometime was not far off. The Twin already was laboring to pump out a meager 70 horsepower in its oneliter form, and upcoming noise and pollution regulations would have made maintaining even the present levels of performance more difficult than squeezing blood from a rock.

BMW, more than anyone, had seen the handwriting on the wall, so it stopped building the R100 models altogether, and has drastically cut the number of 650cc and 800cc Twins that will roll off the production line in the near future. The company’s brand-new manufacturing facility in Berlin will produce 33,000 motorcycles this year an increase of 20 percent over last year 22,000 of which will be K100 models: the standard, unfaired K100 ($5990), the sporty K100RS you see here ($7200), and the touring K100RT ($7500), all of which share the same basic engine and chassis.

What’s even more chancy about BMW's gamble is that the company is playing a hand it dealt itself almost six years ago, back when the decision was first made to build the K100. At that time, the technocrats at BMW were charged with building a machine that would not only meet the projected performance criteria of the Eighties, but one that would offer traditional BMW values longevity, luxury, serviceability and, perhaps most important of all, exclusivity in a market soon to be inundated with exotica from Japan.

Simply put, the Germans needed to build a machine that the Japanese would not. And in the quest for such individuality, many engine configurations were either tried or at least considered. V-types, square-Fours, far-fetched H-designs, even a horizontally opposed fiat-Four was evaluated, although it was abandoned once it was deemed too similar to Honda’s Gold Wing. Eventually, the decision was made to build a new machine powered by a dohc, liquid-cooled, fuelinjected, one-liter inline-Four laid on its, side with its crankshaft running longitur dinally. And after making that commit ment, the powers-that-be at BMW must have gnawed their fingernails to th, quick as new engine designs from Japa;, started bombarding the marketplace all around them.

Luckily for BMW, there were no direct hits. And finally, after five years of development that included 10,000 hours of dyno time and 400,000 kilometers of test riding, the K100 became a production reality for the European market late last year. Now it’s America’s turn. And those who have feared that the precious essence of BMW would somehow be boiled away by the brewing of this new formula need worry no more. Because. the most endearing of BMW qualities are present indeed, maybe even enhanced in the K100.

Now, understand that even though the K100RS tested here looks nothing at all like a Japanese bike and even less like its predecessor, the R100RS, it has been heavily influenced by both. The lazy lope id subdued rumble of the Hut-Twin enne have been replaced with a more urnt, higher-frequency whine, the same nd of four-cylinder song sung by the ne-Fours from the Orient; yet the ¡,c still has the same air of dignity that narked the R100RS. It gobbles up highvay miles in grand BMW' style, but also an be snapped into and out of corners ith a precision and surefootedness that a Boxer could ever match. It's a bike at can be herded along a twisty ribbon road in the company of the best higher for ma nee Japanese iron without losig its stately composure. So in elTect, 's the best of both worlds.

There’s no question that a really fast der on a really competent Japanese bortbike can get from Point A to Point 1 on a w inding road much faster than he ould on a K100RS; but most everyone Ise can ride just as fast, if not faster, on he BMW while not working as hard in ae process. The K100 has the kind ol owerband, the kind of suspension and he kind of overall handling that simply -eke the tine art of riding quickly a hole lot easier.

There is no mystery about how the CIOORS accomplishes this feat; BMW nerely rethought and rearranged existlg technology to tit within some new panmeters. In fact, poking around in the RS's twin-cam, 987cc engine reveals anything hut cutting-edge hardware. T he bore-and-stroke dimensions are unfashionably undersquare (67mm by 70mm, respectively), the cylinder head is of a bog-standard two-valve design, and valve adjustment is via the same type of shim-and-bueket arrangement that has been bumping poppet valves open for decades. Only the narrow, 38-degree included valve angle is in keeping with current trends in engine design.

But there’s a good reason for all of the k 100's apparent low-tech; It tits the requirements imposed by the use of a longitudinal, inline-Four engine of one-liter capacity. Were the cylinders any larger in diameter, the engine would have to be longer, for the bores already are marginall} close together (9mm); and a longer engine would, in turn, mandate either a lengthier wheelbase (which is already quite long) or a shorter swingarm (which, if it were much shorter, would excessively amplify the up-and-down chassis-jacking caused by the shaft drive's torque-reaction). And since that more-or-iess locked BMW' into a smallbore, long-stroke engine (which is not conducive to high-rpm operation), a four-valve combustion chamber (which reaps its biggest benefits at higher rpm) made little sense.

On the other hand, the shim-and bucket valve gear made perfrct sense in the KlOO engine. Not only does that ar rangement meet BMW's requirements for simplicity and long intervals between adjustments, but it allows the camshafts and followers to be easily serviceable just by removing the cam cover on the left side of the motor. So, too, are the Kmodel’s forged, one-piece crankshaft and its attendant plain bearings highly accessible, for they're all located just beneath the easy-to-remove aluminum cover at the right side of the engine.

Like late-model Boxer Twins, the K100 Four uses an electronically applied, nickel/silicon-carbide coating (called “Scanimet”) on its aluminum cylinder bores, which are cast as a unit with the upper er, left-side engine case. Aside from being non-boreable, this coated surface is superior to a castiron liner in terms of thermal conductivity, plus it allows for closer bore-centers, and is lighter and more durable. Durability also was the prime reason for the use of liquid-cooling on the K100. And the fact that previous BMW motorcycles have been air-cooled was no drawback; the company has, after all, been building liquid-cooled BMW automobiles for a long, long time.

BMW’s expertise with automobiles also was put to good use in the adaption of fuel injection to the K100. The bike incorporates a variation of the Bosch LE-Jetronic system used on numerous BMW cars for years. This system utilizes a black-box computer (under the RS’s seat) that, through a series of sensors positioned in key locations in and around the engine, keeps tabs on engine speed and temperature, throttle position, and the air temperature and pressure within the intake tract. That information is analyzed by the computer, which then regulates accordingly the flow of fuel through the injector nozzle situated inW each intake port. But that’s all pret* much standard fare for a fuel-injeett motorcycle, with one exception: On th K100, a Bosch-built electronic fue pump is housed inside of the bike’s 5.i gallon aluminum tank as a part of unique, completely sealed fuel system.

Bosch also supplied the K 100’s elec tronie ignition, which is tied into the ii. jection system’s computer box so it func tions as both a performance aid and rev-limiter. By comparing engine rp with the amount of throttle opening, th ignition effectively selects one of two di: tinct advance curves to work most effe tively with the load that’s being place on the engine. In addition, at 8650 rpr which is just 100 rpm above redline, th ignition automatically retards the timin to deter over-revving. And should th rider ignore that first warning, the com puter then shuts off the fuel-injectic system altogether at 8750 rpm, ar keeps it off until the engine speed dro back down to below 8750 rpm.

That fail-safe capacity is about t most sophisticated aspect of the K100 engine. But otherwise, the bike has >a unremarkable, long-stroke, two-valve relatively low-revving motor that fi? right in with the performance program outlined by BMW’s engineers right from the beginning: strong torque output at exceptionally low rpm, and a healthy if not spectacular peak horsepower production at only moderately high rpm. That’s just what the K100RS has, too. The torque peak is at 6000 rpm, but the engine achieves 85 percent of that peak at 3500 rpm; and the claimed 90 horsepower is delivered at 8000 rpm, still well below the power peak for virtually all comparable Japanese engines.

What those numbers mean is that even though the K100RS isn’t going to win any contests of speed with Japanese weaponry of equal displacement, the bike still is no slouch. Actually, it’s faster than, say, a Suzuki GS850 shafty in just about every conceivable way, from an idling crawl to triple-digit speeds and everywhere in between. And it does that by producing the kind of power that is generally found only on something like a Honda Interceptor—smooth, uninterrupted, linear.

So no matter the situation, whether it’s cruising the open highway or clipping along some remote country backroad at a classic sport-touring pace, the BMW always seems to offer you two, maybe three usable gears to choose from. And although the K100RS admittedly is no FJ 1 100-killing roadburner, it still romped through the quarter-mile in 12.56 seconds and 107.20 mph—not bad, considering that the RS has rather tall gearing, taller, even, than the standard K 100’s.

There’s also an uncanny smoothness in the way the K100 reacts to changes in throttle. Off of idle in neutral, the engine seems to respond slowly, almost with a stumble. But when the bike is in gear and moving along, it offers a nearly perfect compromise between immediate response and gradual reaction. There’s virtually no driveline snatch, no sudden lurches, no tendency to fall on its face, just a turbine-like outpouring of strong, steady power.

There is, however, a glitch or two in the K-bike’s performance program, not the least of which is what seems like a rather fragile clutch. Indeed, in the middle of only the third run down the dragstrip, the single-plate dry clutch in our K100RS fried itself to a crisp. Then there’s the matter of the vibration radiated by this new-wave BMW. Despite being rubber-mounted in the front, the engine buzzes noticeably more than a Japanese inline-Four of comparable size, and certainly more than any Boxer Twin ever managed on its worst day. It’s a fairly high-frequency vibration, too, that is strongest right at about 55 mph in top gear, and it’s felt most often through the footpegs. And the vibes didn’t go unnoticed by the heat shield on the muffler, which self-destructed its front mounting

tab after only a few hundred miles of testing.

That’s the sort of problem the Boxer never had; but by the same token, the K100RS doesn’t pump up and down on its rear suspension the way the R100-series bikes did any time their throttles were opened and closed. And much of that improvement was wrought by what BMW has termed the Compact Drive System. In effect, the engine, the fivespeed transmission and the unsprung mass of the Monolever rear suspension (a unique system using a single shock and a single-leg swingarm that pivots on the transmission case) are all one unit; and the rest of the bike—that is, the frame, with the bodywork and the front suspension attached—bolts to the engine unit and utilizes the engine as the main stressed frame member.

Other than being lighter and simpler, one reason why this arrangement functions so much better than the old design is that the center of the universal joint now is concentric with the swingarm pivot, whereas the two were about an inch and a half apart on the Boxer. On the old-style design, the driveshaft had to change length as the swingarm moved up and down, which required a sliding spline arrangement at the rear wheel. And the slip-fit tolerances of the splines simply added to the Boxer's already problematic driveline lash. But no such monkey-motion is required on the K model, for its driveshaft remains the same length as the rear wheel moves up and down.

So that improvement, along with the use of three low-lash cushion mecha nisms in the driveline (one spring-type cushion and two hard-rubber types) in place of the the two in the Boxer (both of the coil-spring variety), has eliminated most of the driveline freeplay that made riding the old bike smoothly such a chore. Gearchanging on the K-bikes is therefore not the least bit clunky or noisy, and off-on-off throttle transitions are not greeted with the lurching made infamous by the R100 models.

Better yet, the K100 exhibits less of the up-and-down chassis-jacking that is always a concern on shaft-driven bikes. Some of that is due to the fact that the> bike has slightly shorter suspension travel than the Boxer has, some is due to the fact that the rear suspension has stiffer spring rates with more preload and thus will not let the bike move up and down as dramatically. There still is a pronounced rise and fall, especially in the lower gears, but the problem is less exaggerated than it is on the R100 series.

Consequently, low-speed cornering in particular requires a bit of throttle-control to prevent excessive vertical chassis movement. But unlike the opposed-Twin BMWs, which often hammered their undercarriages into the road surface when the suspension compressed quickly, the KIOORS has an abundance of cornering clearance in any case. The bike must be ridden extremely hard before first the footpegs, then the sidestand tang and the centerstand, graze the pavement. And even when something solid does smack the macadam, the RS remains unflinchingly stable.

One reason why the bike displays such good road manners is its use of fairly sticky Metzeler Perfect tires, an 18-inch up front and a fat, 17-incher in the rear. Another is the rigidity of the front fork, a Fichtel&Sachs-built assembly using 41.4mm stanchion tubes held in place by thick aluminum triple-clamps. The fork also features a front axle that has a huge, 22mm diameter to maximize the rigidity of the entire assembly, and the axle also is offset 2.5mm to the rear to increase the trail a like amount.

That sturdy fork is equipped with two very powerful Brembo brake calipers pinching slotted, stainless-steel discs that are 285mm in diameter. The brake pads are semi-metallic and provide consistent, effective stopping ability in both wet and dry conditions. But although the front brake is powerful and requires only twofingered actuation to slow the RS at moderate speed, it calls for a fistful of digits around the lever during high-speed braking. Despite its high-effort action, though, the front brake does not fade, even when used aggressively for long periods of time.

Not so the rear brake, which can be overheated with exceptionally hard use, sometimes badly enough to stop working altogether. And when used in combination with engine braking from fairly high rpm, the brake can also initiate some mild rear-wheel chatter, which is aided by the soft rates of springing and damping in the rear suspension.

BMW has always used long, soft suspension on its motorcycles, it seems; and although the KIOORS has a tad less travel at both ends than the Boxer models of recent years, it is nonetheless plush, compliant and responsive to bumps of all sizes. The fork action is above reproach in just about every respect, with the possible exception of the dive it exhibits during severe braking. The fork offers no external adjustments, but the single rear shock has a ramp-type collar that allows the spring preload to be set at any one of three positions. At its lowest setting, the rear end is pleasantly supple on the highway, but compresses and moves around too much during aggressive cornering. At its highest setting, the shock is best-suited for hauling a passenger and a few days’ worth of luggage. Thus the middle position is the most useful and versatile, offering above-average compliance, sufficient ride-height, and adequate resistance to bottoming.

And it is in those fast, sweeping corners where the KIOORS really shines. Its suspension squats evenly and predictably as the apex is reached, and mid-turn corrections can be made with little effort. The bike is no featherweight, but it carries the bulk of its heft—which is the engine, primarily—in typical low BMW fashion. And so, despite its narrow, 24inch-wide handlebar, the RS can be flicked into a corner or side-to-side quickly and easily. You’ll never be tricked into believing that there’s a 16inch front wheel residing at the front; but with its steep (27.5-degree) steering head angle and short (3.9 inches) front wheel trail, the RS is responsive and uncommonly neutral-feeling at all lean angles, even when braking in a turn.

It’s easy to see, then, how a rider can lock himself into a smooth, relaxed, but extraordinarily fast rhythm on the KIOORS without even trying hard. That’s a fair description of sport-touring, an activity at which the RS performs brilliantly. The seating arrangement is better even than that of the fabled R100RS sport-tourer, for while the two are roughly equal in the swervery, comfort-wise, the K-bike is roomier and more luxurious for use on the open road.

The seat, for example, is padded with softer, thicker foam; and the footpegs have been moved back ever so slightly compared with those on the Boxer, which cants the rider a bit more forward and takes some of his upper-body weight off of his tailbone. And the low, narrow handlebar is designed to keep the rider tucked in behind the fairing so he’s out of the airstream.

One interesting trick BMW employed to keep things calm behind the fairing is the use of an adjustable airfoil just at the top of the windscreen. The foil causes a venturi effect at the top of the screen, accelerating the flow of air back toward the rider’s head. This little wing does not enlarge the envelope of still-air around the rider, but instead just smooths and directs the flow so that the air that does hit the rider's helmet is relatively free of turbulence.

We have no wind-tunnel numbers to substantiate our feelings about the aerodynamics, but we can attest to the fact that the fairing does an excellent job of protecting the rider. One of our testers got caught in a sudden downpour without his trusty rainsuit, but when he stopped he discovered that only his boots and the top of his helmet had gotten wet.

That’s the kind of thing that can forever endear the K100RS to its owner. So too can a host of other well-thought-out niceties, such as: turnsignal housings on the fairing which snap off easily in the event of a tip-over; a taillight that can be popped off in seconds with no tools; an easily removable cam cover and crankcase cover that feature self-centering bolts and reusable rubber gaskets; a rear wheel that can be detached in minutes; and, of course, BMW’s highly acclaimed toolkit, which can actually handle some major engine work, including crankshaft removal. Then there are some real BMW breakthroughs, like a centerstand that is wide enough to provide stability when in use, and a centerstand that not only can be deployed from the saddle, but that won’t retract unexpectedly and let the $7200 K100RS flop on it side.

What’s more, the sidestand incorporates one of the slickest interlock devices ever to hit the market. The sidestand is linked to the clutch via a separate cable so that squeezing the clutch lever also automatically retracts the stand if the bike isn’t resting on it. If it is, the clutch lever simply won’t move. And since the engine will not start in gear without the clutch disengaged, BMW has made it virtually impossible to ride away with the sidestand down.

BMW has also made it impossible for anyone, regardless of their allegiance, to ignore the new K100. The bike has already been voted motorcycle of the year in five European countries; in Germany alone, BMW motorcycle sales have increased a staggering 120 percent since the introduction of the K100 last fall. And with the recent export of the entire K100 family to the U.S., BMW plans to increase its worldwide sales by more than 50 percent.

Ah, but to reach that sales goal, BMW figures that it will have to attract 35 percent of its K100 buyers from the ranks of Japanese-bike owners. And that’s a sword that can cut both ways. Because should the K100 prove too successful, should this upstart motorcycle from Germany make any kind of a noticeable dent in the market-share of the Big Four manufacturers, you can bet your bottom Deustchmark on one thing: The Japanese will figure some way to flop an inline-Four on its side and put together a K 100-clone that'll sell for thousands less. Maybe it won’t be a good clone; maybe it won’t take sport-touring to a new alltime high the way the K100RS has; but it’ll be there, and the mere presence of a Japanese-built K100RS-replica could dilute the market for such a bike just enough to cause big problems for BMW.

We hope it doesn’t come to that. We hope that the Japanese will ignore the small slice of the market that BMW might be able to capture and instead concentrate on bigger, more lucrative segments of the sport. We're willing to wager that they’ll do just that. And so is BMW, obviously.

The difference is that we’ve got nothing riding on that wager. But BMW has bet the whole store on it. Eä

$7200

BMW

K100RS

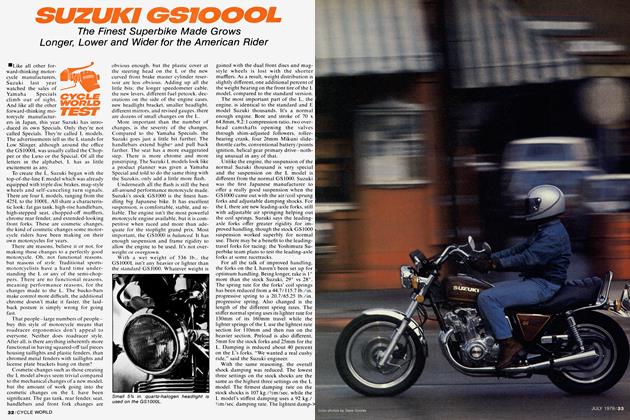

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

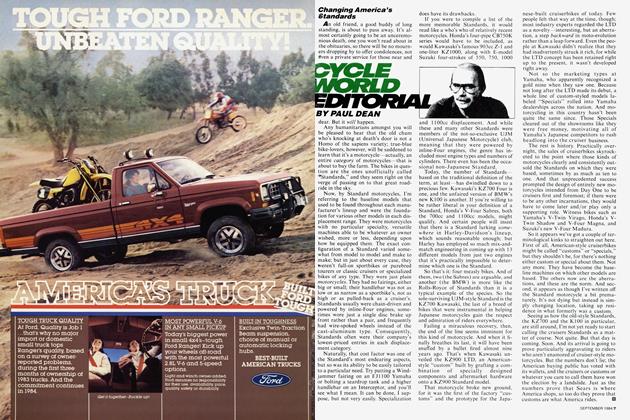

DepartmentsCycle World Editorial

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersCycle World Letters

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Departments

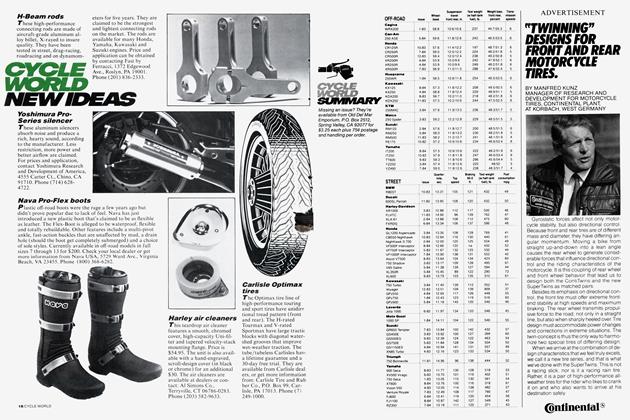

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Features

FeaturesThe Widow

SEPTEMBER 1984 By David Edwards -

Features

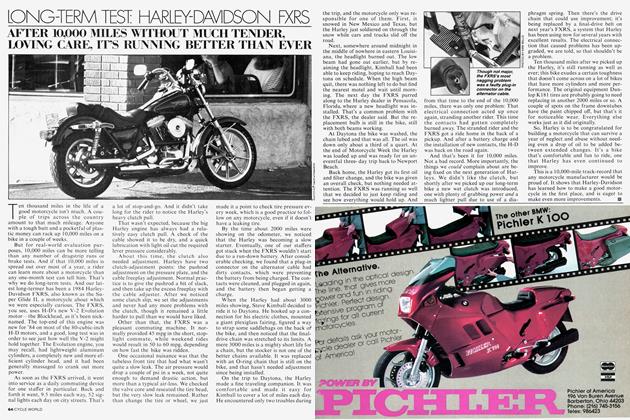

FeaturesLong-Term Test: Harley-Davidson Fxrs

SEPTEMBER 1984