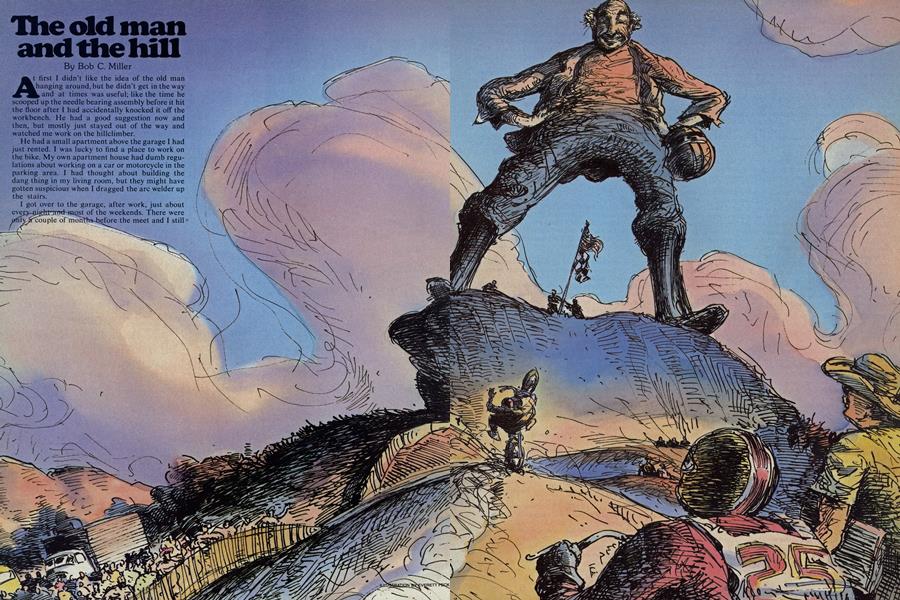

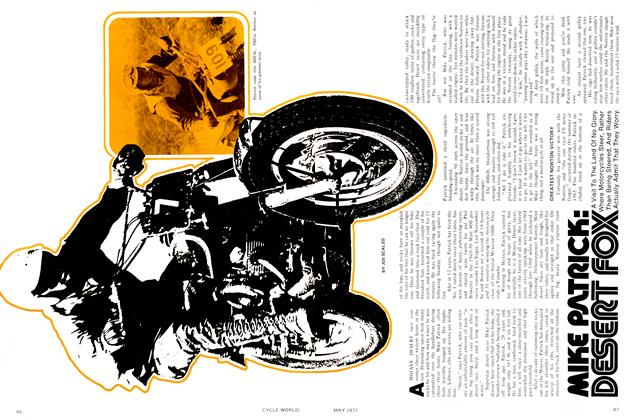

The old man and the hill

Bob C. Miller

At first I didn’t like the idea of the old man hanging around, but he didn’t get in the way and at times was useful; like the time he scooped up the needle bearing assembly before it hit the floor after I had accidentally knocked it off the workbench. He had a good suggestion now and then, but mostly just stayed out of the way and watched me work on the hillclimber.

He had a small apartment above the garage I had just rented. I was lucky to find a place to work on the bike. My own apartment house had dumb regulations about working on a car or motorcycle in the parking area. I had thought about building the dang thing in my living room, but they might have gotten suspicious when I dragged the arc welder up the stairs.

I got over to the garage, after work, just about evej^-mghi^mTd^ÄiQst of the weekends. There were dy^rcouple of monttrsTyefore the meet and I still had a lot of work to do. The engine was already built strong and solid, and I wanted the frame and running gear the same way. I had already completed the frame extension and had decided on a little shorter wheelbase than was normal practice. The special shocks I ordered finally came in and I had to tack on some new mounts. The frame was as light and strong as I knew how to make it. Old Earl had a couple of good ideas on improving the weight distribution, which he had offhandedly offered. After I had thought about ’em, they made pretty good sense, so I used them.

Earl had said he was 65, when I asked him once. With his small wiry frame he might have passed for a much younger man, except for his face. His features were lined with a checkerboard of wrinkles that told of a lifetime of hard work. He had that kind of mottled skin that, no matter how hard he washed it, always looked like he had just finished a day’s work in a dirty machine shop. He was completely bald except for a wisp of silvery white hair above each ear.

Finally the bike was nearly done. I sprayed the tank a bright yellow and added some pretty neat black pinstripes. Earl polished up the engine cases and when we were done the “Beast” looked pretty presentable.

Overall he had been pretty handy to have around. He never really got in the way, but was always close enough to lend a hand if I needed it. I brought Earl along when I took the bike outside of town to try it up a few small hills. These were nothing like the “Backbreaker,” but I got a feel for the handling and traction. Earl watched from the hood of the truck as I tried it out. Between runs he made a suggestion about moving the handlebars a little bit further forward that seemed to help.

I wondered about asking Earl if he wanted to go over to the meet with me. It was about a four hour drive and was going to be a long day, since I planned to drive back that night. I thought it might be too much for an old guy like him, but he said he would go when I mentioned it. He would come in handy unloading the trailer, and could keep an eye on who had borrowed my tools when I was away from the truck.

TOLT

^Pe left a little after 5:30 in the morning and it was a quiet ride. Earl seemed lost in his thoughts and I kept wondering if anyone would conquer the hill this year. There had been climbs for the past three years, but nobody yet had made it to the top. I had watched the runs carefully last year and figured it would take a smaller lighter bike to make it all the way.

We got there in time to get a cherry spot under some trees near the entry official’s table. We registered and Earl seemed especially proud of his “Crew” tag. We unloaded and checked the bike over carefully. Earl fueled it up and I ran the engine for a while. It sounded good so I left it alone. Since we had arrived early I got one of the first starts. I rolled up close to the line and just sat there for a moment looking at the hill. It was almost straight up near the top. Some of the spectators had climbed to the top for a better view, but you couldn’t see them for the steepness.

The starter motioned me forward and I cranked up the engine. As I inched to the line and waited for the flag to drop, the engine sounded strong. I popped the clutch and got off to a good start without too much wheelspin. As I worked at getting up to speed, my concentration was broken when I saw a dog trailing a leash run under the crowd control rope. My first thought was to let the mutt take his chances, then I saw the little girl duck under the rope in close pursuit. The dog made it across in front of me but I had to go around the girl. I swung the bike to the left and put out my foot to keep upright. I felt a dull pain in my knee as the bike pivoted around the girl and then got back on course. My left leg felt a little numb, but I was soon back up to speed. At the quarter way mark a good sized rut bounced me slightly off course, but I recovered and was still running good. The bumps in the flat section at the halfway marker were murderous. I had seen a lot of riders lose it all there. I picked my way through and didn’t lose too much momentum. It was fairly smooth, but steep, up the three-quarter way mark. The engine was pulling fantastically and I knew I might have enough speed to make it all the way to the top.

The last fifty yards were almost straight up. I felt as if I was defying gravity as I surged toward the top. I could now see the heads of the spectators as they looked over the rim of the hill. Only fifty more feet. The rear wheel was spinning wildly now as the incline steepened. I struggled to keep the squirming bike going straight. The front end began to drift to the left. I hauled the front wheel over hard, but it wasn’t touching the ground. I firmly planted my left foot and felt a devastating pain in the knee as the leg gave way. When the bike fell over, the rear wheel continued to dig and the bike spun away. I tumbled a couple of revolutions back down the hill but came up holding my rapidly swelling knee.

E

arl took the bike from a course worker who had been assigned to clear out the bikes of those riders too dumb not to get hurt. I limped painfully along behind as he rolled the bike toward the truck. He put the bike up on the stands and checked my leg over. When he had assured himself that I hadn’t broken anything, he wrapped some ice up in a towel and tied it around my knee.

Earl then checked the bike over quickly and came back to where I was sitting. There was a strange gleam in his clear blue eyes as he stared up at the hill.

“You know, you dang near made it,” he said.

I could tell by the tone of his voice that he was excited. He stood silent for a moment, looking thoughtfully at the hill. His small body was tensed up as if he were about to fight, then a faint smile crept into the wrinkles at the corners of his eyes. He brought his head around and although he was looking straight at me, his gaze was through me.

“I think I could make it.”

“You what?”

“I think I could make it to the top,” he said calmly.

I sat dumbfounded as he picked up my helmet and tried it on. It was two sizes too big but seemed to suit him just fine. He pulled the helmet off and said, “I’ll go tell ’em about the substitution.” He started off toward the officials’ tables, then wheeled and came back to me. “That is, if it’s all right with you?” He took my wide eyed stare as an O.K. and strode off.

I could see him quietly arguing with the officials. At least they had enough sense not to let him try it. Then an older official reached across the table and shook Earl’s hand. The older official conferred with the others, and Earl was soon back wearing a “Rider” tag.

As Earl readied the bike, I was searching for the words to let him down gently. This was crazy, I couldn’t let him go through with it. Before I could protest, Earl picked up the helmet, jerked the bike off the stands and headed toward the start.

“See you at the top,” he smiled.

I was so overcome by his confidence I couldn’t get the words of protest out.

I painfully got to my feet and limped over to where I could see his attempt. He looked like a little kid as he walked the big bike to the starting line. He got astride the machine, adjusted the helmet’s chin strap to the full tight position, and with one determined kick that took all of his 120 pounds, started the engine. He revved the engine a few times, pulled down the goggles, and nodded to the starter that he was ready.

I shook my head at the disbelief of what was happening. There was a 65-year-old dried up little man about to take my> bike up the side of the ‘Backbreaker’. He was going to get killed or broken up at least. I didn’t mind damaging the bike, it could be patched up, but old Earl might end up a basket case for the rest of his life. What would I tell his family? I didn’t even know if he had any family.

I was having mental pictures of having to care for a bedridden old man, when the explosive sound of the start brought me back to reality. As the bike roared off, Earl was crouched low over the tank, his short arms stretched to reach the controls. His start was good, but I lost him in the cloud of dust the spinning rear wheel kicked up as he accelerated on the first flat portion of the run. When he reached the first elevation change he seemed to shoot up the side of the hill like a rocket. I watched openmouthed as he soared through the rough section halfway up. He stood up on the pegs and leaned forward as the bike reached the final steep section. The engine sounds came down from the hill in pulses as the rear wheel lost and then found traction.

Earl was visibly slowing as he neared the peak. The crowd watched silently, frozen in their tracks. As the front wheel lifted, Earl fought to keep the bike going straight up. He appeared to be somehow suspended over the front wheel as he urged the threshing machine the last few feet. Suddenly the bike and rider were silhouetted against the open sky and Earl eased over the top.

a moment there was complete silence, then the crowd broke loose with a wild cheer, and anyone who was near a horn used it. Earl turned the bike around and brought it to the crest. He waved a stubby clenched fist joyously at the crowd.

I was in shock. The ‘Backbreaker’ had finally been conquered by an old man and a borrowed bike he’d never ridden before. It was nearly 20 minutes before Earl got back down the hill and the crowd let go of him so he could get back to the truck. They had carried him back on their shoulders, stopping occasionally so he could kiss some gal who wanted to be a part of the event.

He had a sheepish grin that lasted half of the drive back home. He drove the truck while I sat painfully on the passenger’s side, sharing the space with a silver trophy that was so tall we had to set it on the floor of the truck.

Earl was silent as usual, just that silly grin. Finally as we neared the outskirts of town, he offered, “That trophy’s yours, you know.”

“Mine?” . . . “Are you kidding, you won it.”

“I don’t need no trophy.”

“Look Earl, I appreciate the thought, but you rode the bike to the top, so you get to keep the trophy.”

Earl drove on silently for a few minutes and then said, “If you hadn’t hurt your knee, you’da won it. Besides you was the one who built the bike. So it’s more yours than mine.”

I started to protest when he interrupted, “Anyways, when we get back I’ll show you why I don’t need no trophy.”

We rode silently for the rest of the trip. After we had rolled the trailer in the garage, Earl motioned me upstairs to his apartment. My knee hurt dully, but I sensed that it was important to him so I hobbled up the steps. I had never been in his place before and was surprised at how neat it was. He waved me on into his bedroom. There sitting on the floor was an array of trophys that reached from wall to wall. There were some photographs of a younger Earl astride a motorcycle. The largest trophy read ‘Mid-West Hillclimbing Champion—1949’.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

March 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

March 1984 -

Technical

TechnicalCycle World Follow Up

March 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Round Up

March 1984 -

Competition

CompetitionIt's Okay, We're With the Duck

March 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Special Feature

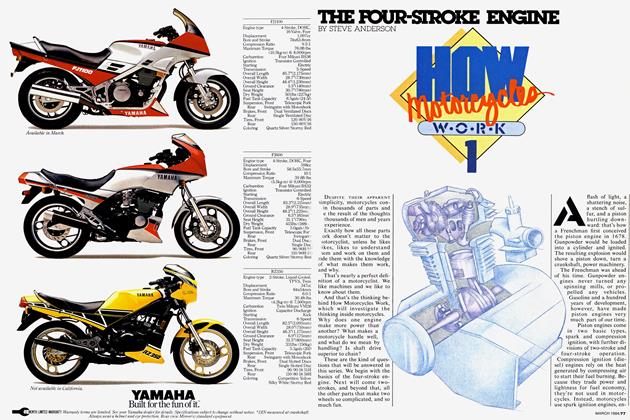

Special FeatureHow Motorcycle W.O.R.K 1

March 1984 By Steve Anderson