CYCLE WORLD BOOK REVIEWS

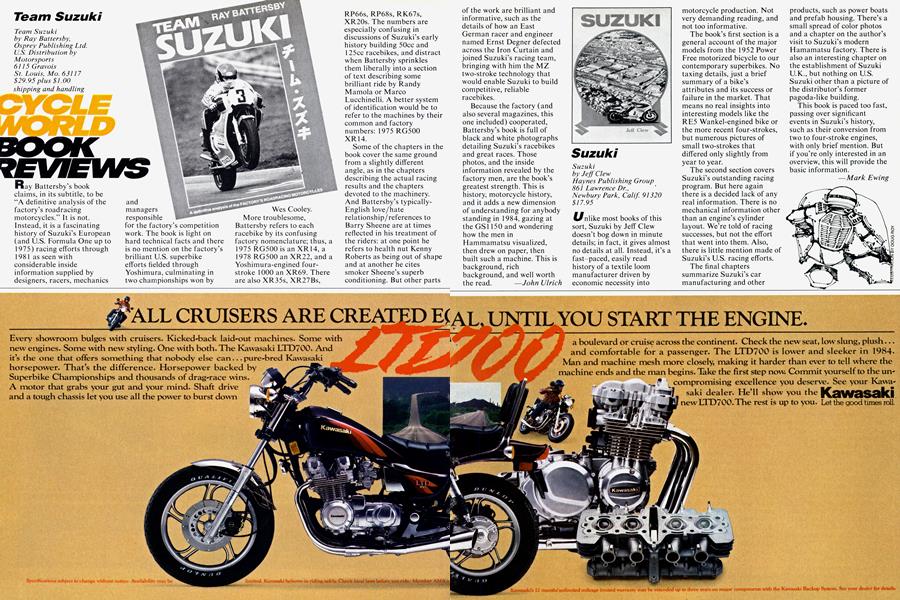

Team Suzuki

Team Suzuki by Ray Battersby, Osprey Publishing Ltd. U.S. Distribution by Motorsports 6115 Gravois St. Louis, Mo. 63117 $29.95 plus $1.00 shipping and handling

Ray Battersby’s book claims, in its subtitle, to be “A definitive analysis of the factory’s roadracing motorcycles.” It is not. Instead, it is a fascinating history of Suzuki’s European (and U.S. Formula One up to 1975) racing efforts through 1981 as seen with considerable inside information supplied by designers, racers, mechanics and managers responsible for the factory’s competition work. The book is light on hard technical facts and there is no mention on the factory’s brilliant U.S. superbike efforts fielded through Yoshimura, culminating in two championships won by Wes Cooley. More troublesome, Battersby refers to each racebike by its confusing factory nomenclature; thus, a 1975 RG500 is an XR14, a 1978 RG500 an XR22, and a Yoshimura-engined fourstroke 1000 an XR69. There are also XR35s, XR27Bs, RP66s, RP68s, RK67s, XR20s. The numbers are especially confusing in discussions of Suzuki’s early history building 50cc and 125cc racebikes, and distract when Battersby sprinkles them liberally into a section of text describing some brilliant ride by Randy Mamola or Marco Lucchinelli. A better system of identification would be to refer to the machines by their common and factory numbers: 1975 RG500 XR14.

Some of the chapters in the book cover the same ground from a slightly different angle, as in the chapters describing the actual racing results and the chapters devoted to the machinery. And Battersby’s typicallyEnglish love/hate relationship/references to Barry Sheene are at times reflected in his treatment of the riders: at one point he refers to health nut Kenny Roberts as being out of shape and at another he cites smoker Sheene’s superb conditioning. But other parts of the work are brilliant and informative, such as the details of how an East German racer and engineer named Ernst Degner defected across the Iron Curtain and joined Suzuki’s racing team, bringing with him the MZ two-stroke technology that would enable Suzuki to build competitive, reliable racebikes.

Because the factory (and also several magazines, this one included) cooperated, Battersby’s book is full of black and white photographs detailing Suzuki’s racebikes and great races. Those photos, and the inside information revealed by the factory men, are the book’s greatest strength. This is history, motorcycle history, and it adds a new dimension of understanding for anybody standing in 1984, gazing at the GS1150 and wondering how the men in Hammamatsu visualized, then drew on paper, then built such a machine. This is background, rich background, and well worth the read. —John Ulrich

Suzuki

Suzuki by Jeff Clew

Haynes Publishing Group 861 Lawrence Dr.,

Newbury Park, Calif. 91320 $17.95

U nlike most books of this sort, Suzuki by Jeff Clew doesn’t bog down in minute details; in fact, it gives almost no details at all. Instead, it’s a fast-paced, easily read history of a textile loom manufacturer driven by economic necessity into motorcycle production. Not very demanding reading, and not too informative.

The book’s first section is a general account of the major models from the 1952 Power Free motorized bicycle to our contemporary superbikes. No taxing details, just a brief summary of a bike’s attributes and its success or failure in the market. That means no real insights into interesting models like the RE5 Wankel-engined bike or the more recent four-strokes, but numerous pictures of small two-strokes that differed only slightly from year to year.

The second section covers Suzuki’s outstanding racing program. But here again there is a decided lack of any real information. There is no mechanical information other than an engine’s cylinder layout. We’re told of racing successes, but not the effort that went into them. Also, there is little mention made of Suzuki’s U.S. racing efforts.

The final chapters summarize Suzuki’s car manufacturing and other products, such as power boats and prefab housing. There’s a small spread of color photos and a chapter on the author’s visit to Suzuki’s modern Hamamatsu factory. There is also an interesting chapter on the establishment of Suzuki U.K., but nothing on U.S. Suzuki other than a picture of the distributor’s former pagoda-like building.

This book is paced too fast, passing over significant events in Suzuki’s history, such as their conversion from two to four-stroke engines, with only brief mention. But if you’re only interested in an overview, this will provide the basic information.

Mark Ewing

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

March 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

March 1984 -

Technical

TechnicalCycle World Follow Up

March 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Round Up

March 1984 -

Competition

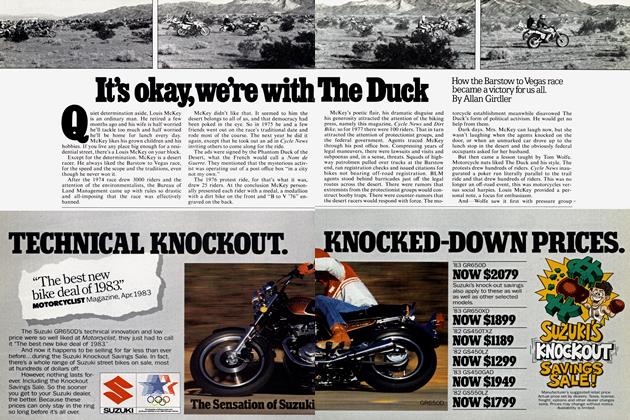

CompetitionIt's Okay, We're With the Duck

March 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Special Feature

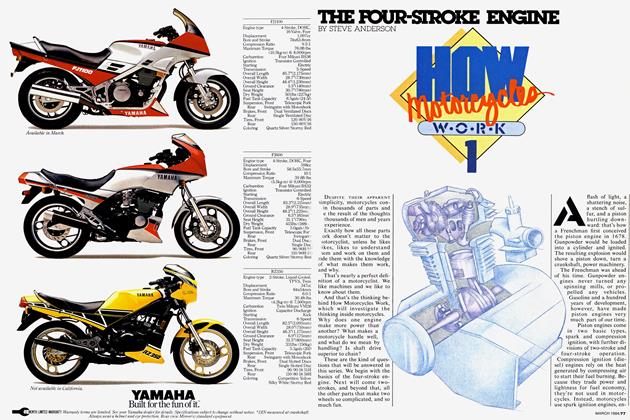

Special FeatureHow Motorcycle W.O.R.K 1

March 1984 By Steve Anderson