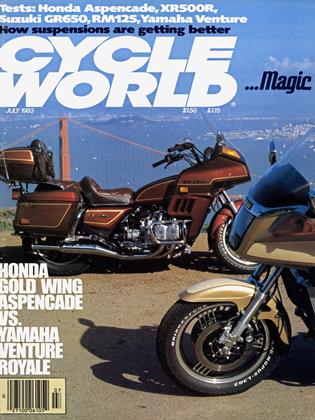

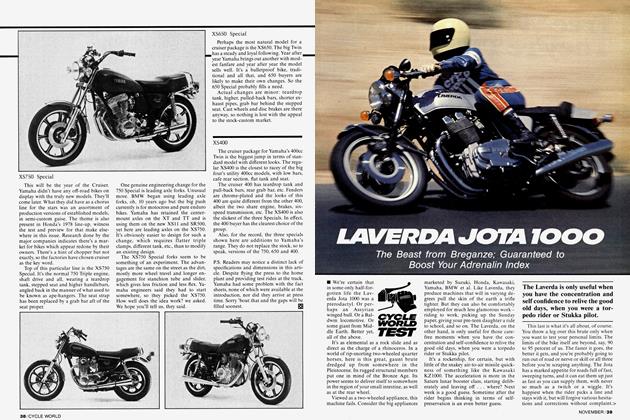

HONDA ASPENCADE VS. YAMAHA VENTURE ROYALE

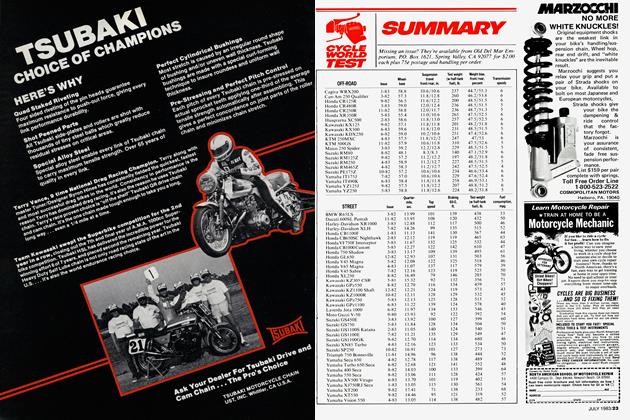

CYCLE WORLD TEST

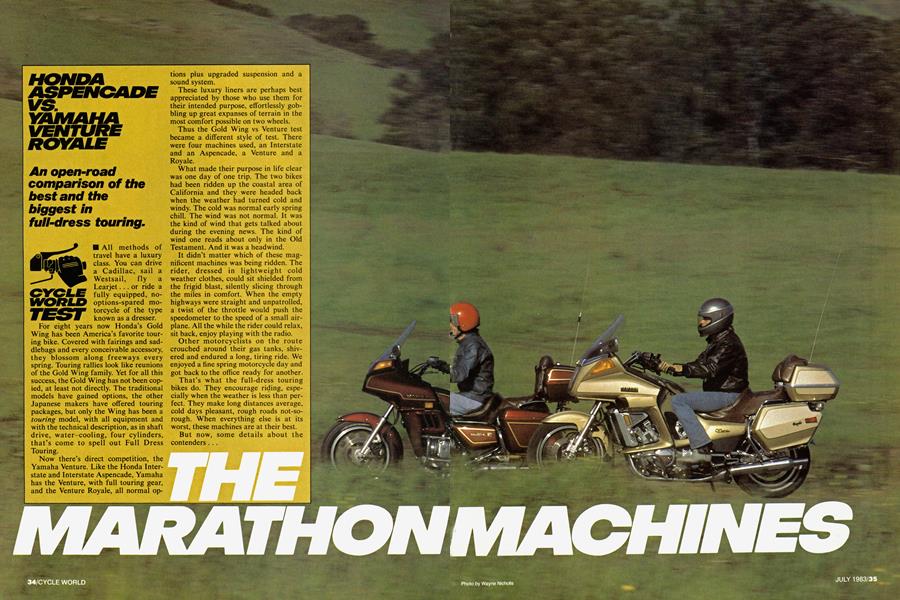

THE MARATHON MACHINES

An open-road comparison of the best and the biggest in full-dress touring.

All methods of travel have a luxury class. You can drive a Cadillac, sail a Westsail, fly a Learjet... or ride a fully equipped, no-options-spared motorcycle of the type known as a dresser.

For eight years now Honda’s Gold Wing has been America’s favorite touring bike. Covered with fairings and saddlebags and every conceivable accessory, they blossom along freeways every spring. Touring rallies look like reunions of the Gold Wing family. Yet for all this success, the Gold Wing has not been copied, at least not directly. The traditional models have gained options, the other Japanese makers have offered touring packages, but only the Wing has been a touring model, with all equipment and with the technical description, as in shaft drive, water-cooling, four cylinders, that’s come to spell out Full Dress Touring.

Now there’s direct competition, the Yamaha Venture. Like the Honda Interstate and Interstate Aspencade, Yamaha has the Venture, with full touring gear, and the Venture Royale, all normal options plus upgraded suspension and a sound system.

These luxury liners are perhaps best appreciated by those who use them for their intended purpose, effortlessly gobbling up great expanses of terrain in the most comfort possible on two wheels.

Thus the Gold Wing vs Venture test became a different style of test. There were four machines used, an Interstate and an Aspencade, a Venture and a Royale.

What made their purpose in life clear was one day of one trip. The two bikes had been ridden up the coastal area of California and they were headed back when the weather had turned cold and windy. The cold was normal early spring chill. The wind was not normal. It was the kind of wind that gets talked about during the evening news. The kind of wind one reads about only in the Old Testament. And it was a headwind.

It didn’t matter which of these magnificent machines was being ridden. The rider, dressed in lightweight cold weather clothes, could sit shielded from the frigid blast, silently slicing through the miles in comfort. When the empty highways were straight and unpatrolled, a twist of the throttle would push the speedometer to the speed of a small airplane. All the while the rider could relax, sit back, enjoy playing with the radio.

Other motorcyclists on the route crouched around their gas tanks, shivered and endured a long, tiring ride. We enjoyed a fine spring motorcycle day and got back to the office ready for another.

That’s what the full-dress touring bikes do. They encourage riding, especially when the weather is less than perfect. They make long distances average, cold days pleasant, rough roads not-sorough. When everything else is at its worst, these machines are at their best.

But now, some details about the contenders.. .

YAMAHA VENTURE ROYALE

I had to be comfortable, convenient, powerful, reliable and carry a big load. Yamaha knew that going in. The Yamaha touring bike’s engine was going to be big. The competition ranged in engine size from lOOOcc to 1340cc. Engine configuration wasn’t so obvious. Lots of choices here, all of them with some strengths and with some weaknesses.

Perhaps because, with the Vision, Yamaha was already building half of an excellent big touring motor, the Venture grew out of that bike. (More likely is that the seeds for both were planted at the same time.) In some senses, the Venture is a double Vision. It is two 70° V-Twins put together, with the liquid-cooling, dual overhead cams, four valves per cyl-

inder and counterbalance shaft used so successfully on the mid-sized Vision.

V-Four engines allow several possibilities for the arrangement of crankshaft throws. Honda has both throws of its VFour cranks in the same position, so both forward pistons move together, and so do the back pistons. Yamaha has taken an alternate approach, with a 180° crankshaft. This puts the two sides of the engine a half revolution out of phase. Honda’s system works because the Honda V-Four is a 90° Vee and is in perfect primary balance. Yamaha’s system works because the counterbalancer evens out the primary imbalance of the 70° Vee and the 180° crank evens out the firing impulses.

Bore and stroke are not the same on the small V-Twin and the big V-Four. The touring bike is less oversquare, 76mm by 66mm bore and stroke. But the compression ratio remains a high 10.5:1.

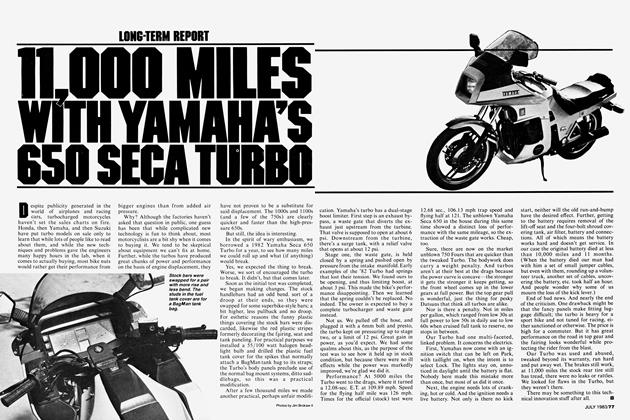

By any measurement, the Yamaha is a detuned motorcycle. While the two-cylinder version of this engine is redlined at 10,500 rpm and easily revs well beyond that the Venture is redlined at 7500 rpm. It has essentially the same valve gear as the Vision and with nothing but a hange of camshafts it, too,could rev to 10,000rpm. But that’s not what touring bikes do, so Yamaha has installed cams with less overlap, for better low-end power and less peak power.

With engine parts capable of handling much higher specific output, the Venture motor should be indestructable. How much power the Venture puts out, Yamaha doesn’t say. But performance figures, compared with the Honda, show that it has substantially more power at every engine rpm.

The Venture motor is also an excellent shape for a touring bike. Nothing sticks out to hit shins or highway. It’s compact,

fitting tightly into the much-shrouded bike. The Venture engine is especially narrow across the cylinders but the flywheel on the left side and the clutch on the right side stick out several inches, not enough to interfere with the rider, but enough to make the Yamaha motor as wide as other engine configurations.

Other parts of the bike fit conveniently around the engine. The four downdraft CV carbs tuck between the cylinder banks and draw their air from an airbox positioned where the gas tank isn’t. The gas is contained under the seat. The engine is relatively short, using only two shafts in the transmission, and this leaves plenty of room for a long swing arm. A long swing arm decreases the rear end lifting under acceleration, and provides room for the suspension linkage connecting the single rear shock to the swing arm.

Yamaha’s Venture Royale has the most sophisticated suspension available on a street bike. Telescopic forks in the front and a single rear shock on the swing arm, are basic. It’s the control over those parts that’s unusual. In back a pair of levers links the shock to the swing arm, making for a progressive suspension rate. Springing front and rear comes from coil springs assisted by air pressure, with pressure controlled by a computer and an air compressor system. (Yamaha calls this its Computer Leveling Air Suspension System, so it has CLASS.)

A small panel of buttons and a liquid crystal display sit on the righthand side of the fairing. Only when the ignition switch is turned to the accessory position can the suspension be adjusted, this to keep riders from adjusting the suspension under way. In practice, you push the button for front or the one for rear and the air pressure in that suspension part is displayed. Another button selects automatic or manual. Push automatic and then you have a choice of three other buttons, low, medium and high. Push one of those buttons and the computer either drains air or turns on the electric pump to increase pressure to a predetermined level. Alternatively, a rider can push front or rear, set it to manual, and then punch the high and low buttons to either raise or lower the air pressure.

The good part of this suspension control is how easy it is to use. The number of buttons is held to a minimum, their use is easy to understand, and the display presents the information in the clearest manner, signaling which end is monitored, what the pressure is, and whether the system is on automatic or manual. The rider doesn’t need to worry about the sensors, dehumidifier, seals or computer. It just works.

A four-position damping adjustment knob on the left side of the bike is just as easy to use. The standard Venture has air valves for air pressure adjustment, and it has damping adjustment in back, but there’s no computer or air pump, and the construction of the rear shock is substantially different. On the fancier Royale, better quality seals are used and the damping adjustment is controlled by a needle valve, instead of the variable orifices used on the standard Venture.

Also on the Venture Royale is an elaborate sound system. Start with a high quality AM-FM stereo radio and cassette deck. Add pushbutton tuning, with five presettable stops on each band. Then make the tuner signal seeking so a push of a button on the handlebars changes station. Throw in a local-distance selector, digital readout and LED function indicators. Then add amplifier controls. Besides volume and tone for the radio and an intercom, there’s a selector for speakers or headphones and a noise-level microphone with adjustment. What this does is vary the sound level of the radio to compensate for ambient sound levels. Set it up to mid-way and as the bike goes faster and makes more noise, the radio volume increases with it. Clever.

The cassette deck has switches for normal or metal tapes, fast forward and reverse, program selector and auto reverse. All these controls are waterproof, but because the tape opening can’t be perfectly sealed, there’s an auxilliary plastic cover for the tape.

Carrying the various electronic components is the job of the fairing. Yamaha Ventures are not available without fairings, saddlebags and rear boxes. The fairing is big. From behind the bike, it looks like a giant wall. Viewed from the side or slightly in front, the fairing has enough shape to look smaller and sleeker. It’s shovel-nosed, with a covered headlight and small windshield at the top of a high dashboard. The inside of the fairing is integrated with the rest of the motorcycle. Instead of the usual gaps between the fairing and the gas tank, the Yamaha’s fairing blends in with the top case and is filled in around the steering head. A simple, easy-to-read instrument panel is mounted at the top of this dashboard, with speakers at the edges, air vents between the instruments and the speakers, and large flat panels below the speakers for the radio and other options. On the standard Venture these are carrying pouches with locking covers.

Big round instruments are used for the 120 mph speedometer and tach, with other needle-type gauges for temperature and a voltmeter. A digital clock is mounted in the center, above a computerized monitor that displays warnings for low oil level, low fluid levels in brakes or battery, any lights inoperative, side stand down or low fuel. A liquid crystal display indicates fuel level. There is no reserve or petcock.

Adjustment, the Yamaha has. Handlbars can be adjusted back and forth and up and down. A knob on the dash adjusts the headlight. Footpegs can be adjusted fore and aft through a range of about 3 in., and the brake and shift levers can be adjusted with the pegs. Even passenger pegs can be adjusted.

Adjusting the brake pedal correctly is important on the Venture, because it gets used more than usual. The Venture has integrated brakes, the pedal operating the rear disc and one of the front discs. The brake lever on the handlebars operates the other front disc. A proportioning valve limits front brake application when the pedal is pushed lightly, then increases front brake pressure when the pedal is pushed harder. All discs are composite-construction ventilated. When either of the front brakes are applied, brake fluid restricts fork compression damping, functioning as an antidive.

The luggage is easily removable, using the same key that opens the luggage and operates the ignition switch. The saddlebags taper in back and fit tightly, with a minimum of protrusions. Despite their unboxlike shape they are large and useful, with small bins at the bottom making it easier to load the saddlebags when they are mounted on the bike. The top box has a padded backrest for the passenger and can hold two full-face helmets. None of the luggage can be opened without a key, and it’s important to set the lock when the luggage is closed, or the lids may pop open.

HONDA GOLD WING ASPENCADE

Much of the Gold Wing's popu larity is due to communication between the engineers respon sible for the design and updating and the people who actually buy the bikes. Wing riders wished for more low-end and midrange torque, and the engine was enlarged from 999cc to 1085cc in 1980. Owners demonstrated an affection for aftermarket fairings and saddlebags and radios and top boxes and engine guards, and soon Gold Wings came off the showroom floor with that equipment already installed, standard.

By now the Gold Wing needs little introduction. Back in 1975 the water cooled opposed Four with crankshaft aligned fore-and-aft, single overhead cams driven by toothed belts, gearbox mounted below the crank and running in the opposite direction to counter engine torque, was nearly revolutionary, more car than motorcycle. But it’s proven to be smooth, strong and silent with a durability quotient that really is more car than motorcycle.

Honda hasn’t muddled the basic package. In 1980 the displacement was increased, and in 1983 1st gear was lowered and the secondary ratio, between clutch hub and gearbox input shaft, was raised: 1st is thus unchanged, for easy starts in traffic and 2nd through 5th are higher, for reduced engine speed for a given road speed.

Another once-radical feature is the fuel tank under the seat while what looks like the tank houses electrical connections, the overflow tank for the radiator, the fuel filler and the air compressor for the suspension.

The suspension itself, telescopic forks and dual shocks, is more basic than the Venture’s. The Aspencade this year uses steel springs with air supplement, de-

signed to work at lower initial pressure for better response to small inputs. The forks have a flat brace between the legs, above the fender, and both legs include Honda’s adjustable TRAC anti-dive, which increases compression damping (reducing front end dive) when the brakes are applied.

The three disc brakes are radially ventilated, with twin-piston calipers. The rear disc and the right front disc are linked through a proportioning valve; pushing the rear brake pedal also activates the front brake. The proportioning valve directs about 60 percent of the braking pressure to the front disc when the pedal is first depressed, and that proportion increases progressively with line pressure. The left front disc is controlled by the usual handlebar lever.

The bolt-on saddlebags have the rear turn signals built in, and two locking helmet holders are located on the saddlebag guard bars. Removable soft sacks fit into

the saddlebags and there’s a complete tool kit (in a leather tool roll) in the right saddlebag. That tool kit includes a socket wrench and sockets and a selection of full-size open-end wrenches as well as the usual pliers and multi-bit screwdriver. The top box can be quickly removed from the rear rack by unlocking two fittings with the ignition key, and has room for two full-face helmets. Inside the top box is a vanity mirror covered by quilted vinyl. On the front of the box, at the passenger’s back, are two small, zippered vinyl pouches and a back pad.

The top box is mounted about an inch further back than it was in 1982, and the back pad is almost an inch higher on the box, both changes designed to increase passenger comfort. The seat is about an inch narrower where the passenger’s knees are, and the passenger seat itself is more than an inch farther rearward. The passenger pegs are adjustable.

Like the side panels, front fender, false tank, top box and saddlebags, the Gold Wing’s fairing is made of ABS plastic. It is color matched to the rest of the bike, in this case featuring two tones of maroon with gold pin striping. The Lexan windshield’s height is adjustable, and the front turn signals are built into the fairing’s leading edge on each side. Chrome, rectangular mirrors bolt to the fairing just above the turn signals. Waterproof speakers and a removable, key-secured, plug-in-plug-out AM/FM stereo radio are built into the fairing, with a LED display indicating radio station, or, at the touch of a button, time of day. A voltmeter is standard, but LED displays showing volts and ambient temperature ($110) and CB station (included with the optional CB radio, $329) are available. The fairing includes two pockets, or gloveboxes, one on the left covered by a snap-on soft vinyl cover and one on the right secured by a locking, hard-plastic cover. There’s an optional cassette tape player ($230), also key-secured and easily plugged in or out, which fits into the left glovebox. There’s an intercom system with helmet microphones and speakers ($129) which, like the CB module, attaches to the stereo radio unit. Each of the available modules has its own volume control and there’s a cluster of remote thumb levers above the left grip, allowing the rider to mute radio volume (as when rolling up to a stop sign) or change radio station (up only). A push-to-talk lever and a CB channel lever comes with the CB.

Beyond the audio gear, there’s a collection of liquid crystal displays mounted in an instrument pod on the upper triple clamp, including a fuel gauge, engine temperature gauge, digital speedometer, bar-graph tachometer, digital tach readout, digital gear indicator, and a multi-function tripmeter. There are also turn signal, high-beam, neutral and oil pressure warning and oil/filter change interval lights. There’s a conventional odometer, but with seven digits instead of the usual six, so it will read to a million miles.

Just beneath the instrument cluster is a selection of control buttons and the ignition/fork-lock switch. There’s button that turns on the digital tach readout and another to make the speedmeter read in kph instead of mph. Five buttons deal with the tripmeter, which can indicate accumulated trip mileage, mileage between gas stops, mileage to gas stop or mileage to destination, doing any two things at once. Four larger buttons control the air pressure in the forks and rear shocks. Push the button marked “Front” and the coolant temperature bar gauge changes to a fork air pressure bar gauge. Pushing the button marked “Increase” raises air pressure in the forks while the rider watches, and the “Decrease” button reduces air pressure. The same goes for the rear shocks when the “Rear” button is depressed. Suspension air pressure can be changed whenever the bike is at a standstill and the key is on, whether or not the engine is running and whether or not the bike is on the centerstand.

The Aspencade has more mundane controls, too, the usual high beam/low beam, horn, choke and turn signal controls on the left handlebar pod, and electric starter and engine cutoff switches on the right. The turn signals are self-cancelling and now switch, off after a lane change, by measuring distance covered and comparing it to speed.

COMFORT

JV o numbers can be used to measure comfort. Comfort isn’t even noticeable on motorcycles, generally. It’s discomfort that a rider feels when a seat is hard, or the wrong shape, or a motorcycle vibrates too much, or is noisy, or the controls are hard to operate and don’t fit.

Both the Honda and Yamaha have discomfort well under control. Engine sounds are barely perceptable. Vibration is about like an electric fan. The bikes are both big, where a rider and passenger can stretch out and move around some. Both fairings do remarkable jobs of eliminating wind blasts. Measured in terms of isolating a rider from the discomforts of the highway, these are the two most comfortable motorcycles yet produced.

And they are different. Vibrations come through at different times. On the Honda, it’s during deceleration or when the throttle is opened at low engine speeds. Then the whole bike rattles annoyingly. On the Yamaha there’s a pulse to the engine’s irregular firing. It’s reminiscent of a Harley, but a Harley parked in the garage, while you sit in a recliner watching reruns of Route 66. At highway speeds the Honda is smoother.

Exhausts are so muffled that passing cars make more noise. There’s a little primary gear whine on the Yamaha, only when it’s running at 75 mph with a tailwind. The rest of the time only that faint murmur of an exhaust can be heard. That, or the stereo.

Seats on both bikes are wide, have tall back supports, and are well padded. The Honda padding is firmer, and it has a slight lump in front and rise in back, that, initially, is less comfortable. After a few hours on the road, a rider can settle into either one, though the Yamaha is easier to move around on and feels better at the end of the day.

How the rest of the motorcycle fits around the riders is an area of marked contrast. The Honda is built around a rider in one position. If you are the Honda rider, the Gold Wing will likely fit you like a glove. Other sizes or shapes may have problems. There is no adjustment to the handlebars, other than rotating them in the clamps. Honda has limited the adjustment of levers on the handlebars, which restricts handlebar placement. The seat can be moved forward and backward through a range of 2 in., but that isn’t much help. The shift lever is affixed in one position, and that’s too high. The handlebars gave riders a pain in the neck after two or three hours on the road. The pegs would be better farther forward, but that can’t be done because the engine’s in the way. Worst of all are those engine guards. They extend so far to the rear that riders routinely knocked their shins on the bars when putting their legs out at stops. With its adjustments and more compact engine the Yamaha has none of these problems.

One surprising source of discomfort on both bikes is engine heat. These are big engines and they put lots of heat through the radiators. The fairing lowers do a good job of protecting legs from fresh air, and this makes for more heat on the legs. The Yamaha has adjustable fresh air vents on its lowers, and these help slightly, but they aren’t as effective as the vents on the Yamaha Vision. On a 70° day riders on both bikes were comfortable in normal pants and light leather jackets. When the temperature rose to 75° riders were uncomfortably hot, and at 80° they felt like a pizza in the making. This heat and wind protection is fine in cold temperatures, but there should be more control over this heat.

Suspension compliance and control was a small factor in rider comfort. Both bikes have reasonably compliant suspensions, and they can be easily adjusted to virtually eliminate suspension bottoming, even when loaded with passengers and luggage. The Yamaha had a slightly more compliant suspension, particularly in back. The damping adjustment also made noticeable changes in suspension feel, from a floaty, pillow-soft feeling at minimum damping to a tightly controlled ride at maximum. When the Honda’s forks were pumped to high air pressure, they would routinely top out, making loud, annoying clanging sounds.

CONVENIENCE

WÊÆÊJWhen used for traveling, a motorcycle develops a character. It comes from little things, like the ease of gas up, or how it is to load, or if there is some irritating noise.

A lot of work has gone into both bikes to eliminate inconvenience. Turn signals are self cancelling. One key operates all the locks. Tuning and muting buttons for the radios are mounted on the handlebars, so a rider doesn’t have to remove his hand from the bars to change stations.

Differences are most apparent in the controls and instrumentation. Ventures, plain and fancy, share the same instrument panel, mounted in the fairing. It’s easy to read, a reflection from the panel under some conditions the only distraction. All the radio controls are conveniently close to the rider’s left hand and are easy to understand and use. The clock at the top of the dash is particularly useful. The Honda comes in a wider range of models, from bikes without fairings, to the Aspencade with its digital instrumentation. The various controls and gauges are scattered, rather than grouped, and it can be difficut to find the information needed. The liquid crystal display can’t be read in some lighting conditions, the clock is only displayed when a button is pushed, and that button can be hard to find. Another button has to be pushed for the tach to display any numerals. Multiple other buttons do various things to the trip odometer. The radio controls on the handlbar interfere with the headlight beam control, and the other radio controls are confusing to use.

Two causes for the jumble of instrumentation come to mind. One, the Aspencade has been built up, over a number of years, with one feature added on top of another feature. This fairing is used on lots of different Honda models, and features exclusive to the Gold Wing have to be added to the fairing, or hung on the bike. Second, Honda has noted the number of accessories piled on Gold Wings and has responded by putting more buttons on the bike than are necessary, which interferes with the operation of the motorcycle.

A couple of the Yamaha’s controls are particularly pleasing. The automatic volume control on the radio is wonderful. People who like to listen to the radio around town didn’t have to pull up to a stop light and either touch a button or leave the radio blaring. The computercontrolled suspension is also simple to operate, and the changes in air pressure and damping make a noticeable difference.

Neither bike has ideal luggage. The top boxes are the easiest pieces to use on either bike, and hold a surprising volume. But the saddlebag lids on the Honda can be difficult to install, and there are times when it would be easier to have demountable saddlebags. Here, the Yamaha scores with an excellent mounting-demounting system for the saddlebags and the top box. Except that the Yamaha luggage can’t be opened without a key, and closing the sides of the saddlebags can be more time consuming than it should be.

Maintenance is not an enviable chore on either bike. Even such common tasks as tire changing is time consuming enough to discourage most owners. The Gold Wing, however, has easy to adjust valves and many of the engine components are out in the open. The Yamaha has everything behind a cover of some sort. A valve adjust on the Yamaha requires special tools, shims and lots of parts removal.

Tool kits on both bikes are elaborate, even including socket sets and Crescenttype wrenches.

Both gas tanks hold only 5.3 gal. and this isn’t enough. Fuel mileage was identical on the two bikes when traveling. Hard riding into headwinds on the highway dropped mileage to 35 mpg, normal was 40 to 45 mpg. The Yamaha ran fine on any fuel, the Honda did not. It would ping at low rpm, high load conditions when unleaded or regular gas was used. Under most conditions the bikes indicated reserve or low fuel at about 150 mi. If the gas gauges were more accurate and you could count on finding a gas station just when you wanted one, either of these bikes could just go 200 mi. between fillups. Ridiculous. Around town the Yamaha got much better mileage. On the town and country CW mileage loop, the Honda got 40 mpg, the Yamaha 47.

PERFORMANCE

Touring bikes need performance, too, even though it may be a different type of performance from that of a muscle bike. They need to carry big loads, they should accelerate strongly, hills and headwinds shouldn’t slow them. There is no reason a touring bike shouldn’t handle well and be stable. And braking power is vital because of the extra weight these bikes often carry.

Top gear acceleration is a more telling measure of performance for these bikes than quarter-mile figures. Roll-on figures indicate how the engine works over a range of engine speeds. Quarter-mile time measures peak power.

In roll-on tests, the Yamaha is dramatically stronger than the Honda. It should be, with a larger engine, and an engine with more power potential. At the lowest engine speeds the Yamaha has its greatest advantage. Rolling on the throttle at idle, the Honda bucks and vibrates, the Yamaha begins accelerating. Below 3000 rpm is where the Yamaha has its greatest advantage. This is also the range where these bikes can be easily ridden. Because the Honda has a noticeably smooth engine speed around 3000 rpm, and it gets rougher above 4000 rpm, it is usually ridden in this comfort band. The Yamaha doesn’t care how fast or slow the engine is revved. It makes the same chuffing sounds at all rpm.

Putting large loads on the bikes exaggerates the difference. That’s where the low-speed pulling power of the Yamaha really shines.

Braking performance is comparable. Riders used to normal braking systems had difficulty taking advantage of the linked brakes, and were disturbed by the lack of front braking response to lever effort. The Honda had an especially spongy lever, though the Yamaha wasn’t much better.

Handling is more something you cope with than enjoy. Neither bike allows the rider to see—or even feel—where the front wheel is. Riders not used to full dressers may be surprised by the cumbersome steering at low speeds.

The Honda has its mass as low as possible, which helps the bike change directions, but the mass on the steering head is great and it takes more effort to control the Honda at low speeds. The Yamaha, which weighs 12 lb. more, is easier to balance at low speeds. It feels more responsive to input, and because there is better power at low speeds, it’s more responsive to throttle and clutch control.

On freeways, both bikes are stable and secure. The Honda loses its cumbersomeness at speed, and seems more easily moved by cross winds. At high speeds the Honda can also wallow, though increasing air pressure in the suspension reduces this slightly. The Yamaha only wallows at high speeds when the suspension is at minimum air pressures and the damping is at the softest setting. That damping knob has the greatest effect on high speed weave, and when it’s set above No. 1, the Venture is marvelously stable at high speeds, even in strong crosswinds.

Cornering clearance isn’t something often mentioned by touring riders, but it may be a more important limit on these bikes than on more sporting machinery, simply because these bikes have less of it. It is easier to scrape things on these bikes than on an Interceptor. Suspension adjustments have a strong influence on cornering clearance. At higher air pressures, both bikes had adequate clearance for their station in life.

Overall, the Yamaha wins performance evaluations, with more power, better handling and easier control. That other limit of touring performance, carrying capacity, is a draw. The GVWR leave 400 lb. capacities with half-full tanks, though both bikes are likely to be overloaded, and both can handle moderate overloading.

CONCLUSION

el efore jumping to some etchedin-stone conclusion about the superiority of one of these machines, it’s worth noting just how capable both are. These bikes can be loaded with pairs of people, supplies for a week’s journey, and set off in any direction with roads utterly without concern for the motorcycles. As long as they are maintained properly, they can be driven nonstop (if you could fuel with the engine running) coast to coast without concern for overheating, burning oil, chain adjustment, chain lubing or routine maintenance. Oil changes and valve adjusts only need be done at 7500 mi. intervals.

Riders on these bikes are protected from wind and rain as best possible. Even without rain gear, riders can go through light showers without getting soaked. Headwinds disappear. So do expansion joints on freeways, potholes on back roads and worries back home.

These bikes have a magical ability to isolate a rider from noise, vibration, winds and cold. Because .of that, they aren’t for everyone. They are built for people who want to carry themselves and lots of possessions at any speed they choose anywhere they want with the least fatigue. This, they do better than anything else on two wheels.

The Honda has a loyal following, which it didn’t get by accident. It was earned with years of reliable service and with qualities no other motorcycle offered. The Gold Wing remains a strong, silent, troublefree touring bike, with few flaws and many attributes.

Then there is the Yamaha. It has no track record, but it exhibited no cause for concern in 3000 mi. of testing, either. It is faster, more comfortable and more convenient to use in all varieties of riding. It is a carefully refined improvement on Honda’s Gold Wing. It is, for a variety of reasons, a better touring bike, though the gap is small.

THE MARATHON MACHINES

$7599