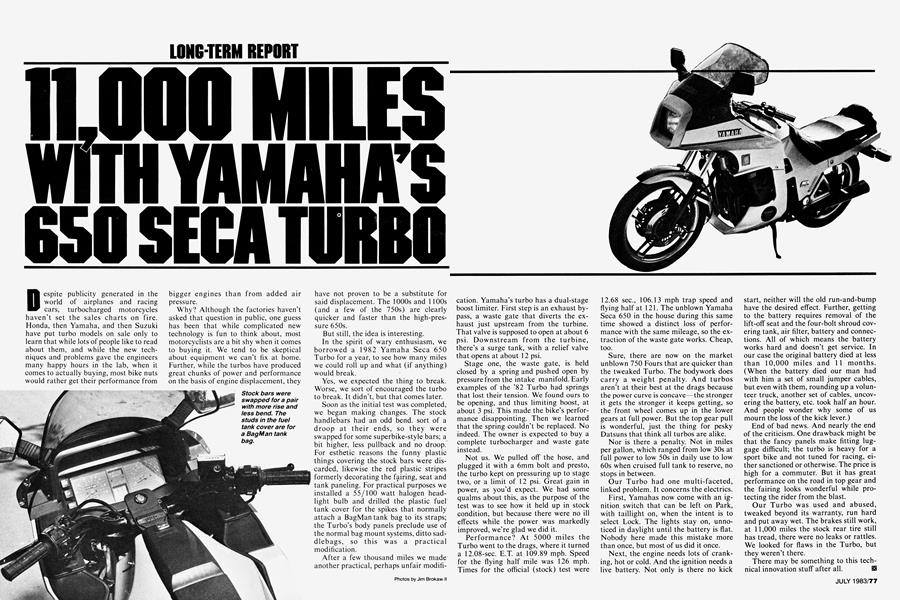

11,000 MILES WITH YAMAHA'S 650 SECA TURBO

LONG-TERM REPORT

Despite publicity generated in the world of airplanes and racing cars, turbocharged motorcycles haven’t set the sales charts on fire. Honda, then Yamaha, and then Suzuki have put turbo models on sale only to learn that while lots of people like to read about them, and while the new techniques and problems gave the engineers many happy hours in the lab, when it comes to actually buying, most bike nuts would rather get their performance from bigger engines than from added air pressure.

Why? Although the factories haven’t asked that question in public, one guess has been that while complicated new technology is fun to think about, most motorcyclists are a bit shy when it comes to buying it. We tend to be skeptical about equipment we can’t fix at home. Further, while the turbos have produced great chunks of power and performance on the basis of engine displacement, they have not proven to be a substitute for said displacement. The 1000s and 1100s (and a few of the 750s) are clearly quicker and faster than the high-pressure 650s.

But still, the idea is interesting.

In the spirit of wary enthusiasm, we borrowed a 1982 Yamaha Seca 650 Turbo for a year, to see how many miles we could roll up and what (if anything) would break.

Yes, we expected the thing to break. Worse, we sort of encouraged the turbo to break. It didn’t, but that comes later.

Soon as the initial test was completed, we began making changes. The stock handlebars had an odd bend, sort of a droop at their ends, so they were swapped for some superbike-style bars; a bit higher, less pullback and no droop. For esthetic reasons the funny plastic things covering the stock bars were discarded, likewise the red plastic stripes formerly decorating the fairing, seat and tank paneling. For practical purposes we installed a 55/100 watt halogen headlight bulb and drilled the plastic fuel tank cover for the spikes that normally attach a BagMantank bag to its straps; the Turbo’s body panels preclude use of the normal bag mount systems, ditto saddlebags, so this was a practical modification.

After a few thousand miles we made another practical, perhaps unfair modification. Yamaha’s turbo has a dual-stage boost limiter. First step is an exhaust bypass, a waste gate that diverts the exhaust just upstream from the turbine. That valve is supposed to open at about 6 psi. Downstream from the turbine, there’s a surge tank, with a relief valve that opens at about 12 psi.

Stage one, the waste gate, is held closed by a spring and pushed open by pressure from the intake manifold. Early examples of the ’82 Turbo had springs that lost their tension. We found ours to be opening, and thus limiting boost, at about 3 psi. This made the bike’s performance disappointing. Then we learned that the spring couldn’t be replaced. No indeed. The owner is expected to buy a complete turbocharger and waste gate instead.

Not us. We pulled off the hose, and plugged it with a 6mm bolt and presto, the turbo kept on pressuring up to stage two, or a limit of 12 psi. Great gain in power, as you’d expect. We had some qualms about this, as the purpose of the test was to see how it held up in stock condition, but because there were no ill effects while the power was markedly improved, we’re glad we did it.

Performance? At 5000 miles the Turbo went to the drags, where it turned a 12.08-sec. E.T. at 109.89 mph. Speed for the flying half mile was 126 mph. Times for the official (stock) test were

12.68 sec., 106.13 mph trap speed and flying half at 121. The unblown Yamaha Seca 650 in the house during this same time showed a distinct loss of performance with the same mileage, so the extraction of the waste gate works. Cheap, too.

Sure, there are now on the market unblown 750 Fours that are quicker than the tweaked Turbo. The bodywork does carry a weight penalty. And turbos aren’t at their best at the drags because the power curve is concave—the stronger it gets the stronger it keeps getting, so the front wheel comes up in the lower gears at full power. But the top gear pull is wonderful, just the thing for pesky Datsuns that think all turbos are alike.

Nor is there a penalty. Not in miles per gallon, which ranged from low 30s at full power to low 50s in daily use to low 60s when cruised full tank to reserve, no stops in between.

Our Turbo had one multi-faceted, linked problem. It concerns the electrics.

First, Yamahas now come with an ignition switch that can be left on Park, with taillight on, when the intent is to select Lock. The lights stay on, unnoticed in daylight until the battery is flat. Nobody here made this mistake more than once, but most of us did it once.

Next, the engine needs lots of cranking, hot or cold. And the ignition needs a live battery. Not only is there no kick

start, neither will the old run-and-bump have the desired effect. Further, getting to the battery requires removal of the lift-off seat and the four-bolt shroud covering tank, air filter, battery and connections. All of which means the battery works hard and doesn’t get service. In our case the original battery died at less than 10,000 miles and 11 months. (When the battery died our man had with him a set of small jumper cables, but even with them, rounding up a volunteer truck, another set of cables, uncovering the battery, etc. took half an hour. And people wonder why some of us mourn the loss of the kick lever.)

End of bad news. And nearly the end of the criticism. One drawback might be that the fancy panels make fitting luggage difficult; the turbo is heavy for a sport bike and not tuned for racing, either sanctioned or otherwise. The price is high for a commuter. But it has great performance on the road in top gear and the fairing looks wonderful while protecting the rider from the blast.

Our Turbo was used and abused, tweaked beyond its warranty, run hard and put away wet. The brakes still work, at 11,000 miles the stock rear tire still has tread, there were no leaks or rattles. We looked for flaws in the Turbo, but they weren’t there.

There may be something to this technical innovation stuff after all. S