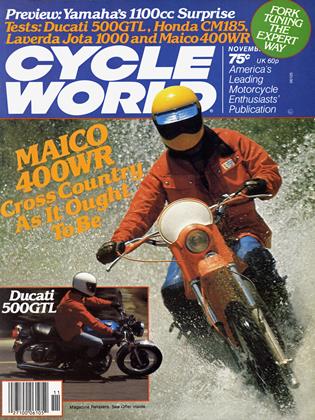

LAVERDA JOTA 1000

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Beast from Breganze; Guaranteed to Boost Your Adrenalin Index

We're certain that in someonly half-forgotten life the Laverda Jota 1000 was a pterodactyl. Or perhaps an Assyrian winged bull. Or a Baldwin locomotive. Or some giant from Middle Earth. Better yet, all of the above.

It’s as elemental as a rock slide and as direct as the charge of a rhinoceros. In a world of rip-snorting two-wheeled quarter horses, here is this great, gaunt brute dredged up from somewhere in the Pleistocene. Its rugged structural members put one in mind of the Bronze Age. Its power seems to deliver itself to somewhere in the region of your small intestine, as well as at the rear wheel.

Viewed as a two-wheeled appliance, this machine fails. Consider the big appliances marketed by Suzuki, Honda, Kawasaki, Yamaha, BMW et al. Like Laverda, they produce machines that will in varying degrees pull the skin of the earth a trifle tighter. But they can also be comfortably employed for much less glamorous workriding to work, picking up the Sunday paper, giving your pre-teen daughter a ride to school, and so on. The Laverda, on the other hand, is only useful for those carefree moments when you have the concentration and self-confidence to relive the good old days, when you were a torpedo rider or Stukka pilot.

It’s a rocketship, for certain, but with little of the snakey air-to-air missile quickness of something like the Kawasaki KZ1000. The acceleration is more in the Saturn lunar booster class, starting deliberately and leaving off . . . where? Next week is a good guess. Sometime after the rider begins thinking in terms of selfpreservation is an even better guess.

The Laverda is only useful when you have the concentration and self confidence to relive the good old days, when you were a tor pedo rider or Stukka pilot.

This last is what it’s all about, of course. You throw a leg over this brute only when you want to test your personal limits. The limits of the bike itself are beyond, say, 90 to 95 percent of us. The faster it goes, the better it gets, and you’re probably going to run out of road or nerve or skill or all three before you’re scraping anything. The Jota has a marked appetite for roads full of fast, sweeping turns, and it can eat them up just as fast as you can supply them, with never so much as a twitch or a wiggle. It’s happiest when the rider picks a line and stays with it, but will forgive various hesitations and corrections without complaint.>

Although its handling characteristics seem rather heavy for ordinary street use, it becomes almost nimble when it gets up to operating speeds (somewhere in the vicinity of escape velocity). You can flop it this way and that, alter your line in mid-turn, brake for unexpected obstacles, deal with decreasing radius—all at speeds that confirm your mother-in-law’s worst suspicions about you—while the bike remains rock steady. It has an almost Prussian willingness to follow orders and is virtually devoid of any caprice. One of our test crew felt it was a difficult bike to love, although he conceded that it was easy to respect. But there’s definitely some soul down there somewhere. Maybe it’s not exactly the verve you’d expect in an Italian racing bike, but consider this: The primary corporate reason for the existence of Moto Laverda is the manufacture of agricultural machinery. The motorcycle is thus a 140mph road rocket cut from the same sort of heavy-duty stock one finds in tractors. We can only presume that this activity continues because it brings joy to Massimo Laverda himself, and we can only w ish that there were more like him.

One of the nice things about manufacturers wffio march to their own beat is that their products are frequently intriguing. The Laverda 981cc Triple is an excellent case in point. For one thing, it's built to endure—just looking at it you get the feeling the barrels and crankcase may have been turned up complete at some granite quarry rather than cast—and endure it has, successfully so, in a number of European endurance road races. Another individual touch is the 180-degree crank, the only Triple we know of with this configuration. The two outer pistons fire alternately but move up and down together, with the center piston set dead opposite. The crankshaft turns in five main bearings—the bottom end will probably outlive the Coliseum—and the hefty cam chain runs between cylinders no. 2 and 3. The cams ride in removable (hence replaceable) bushings and must be removed for valve adjustment, which is accomplished by the addition or subtraction of shims that ride inside inverted cups on the valve stems.

The cams, incidentally, are one of the main differences between the high performance Jota engine and the standard Laverda 1000. They’re ground for a little more lift and duration. The combustion chamber is the same as the ordinary—if any of these Laverda growlers can be said to be ordinary—but the higher crowned pistons are good for a 1.5-point boost in compression. Intake (34.8mm) and exhaust (40.4mm) valves are shared by the Jota and its standard model brother, but the Jota’s 3-into-l-into-2 exhaust setup doesn’t offer quite as much back pressure. This is apparent the instant you light up, and about all we have to say on the general subject of noise is that this piece will definitely get you into trouble with that old lady down the block who thinks all motorcycles are Lucifer’s handiwork. Even our tech ed found the Jota’s authoritative bark a bit much at times. Others felt it enhanced the whole experience of straddling the brute. We guarantee the EPA will find it unAmerican.

The engine itself puts out a volume of mechanical noise that’s audible above the exhaust even at brisk speeds. Laverda has installed a cam chain resonance damping shoe in the front of the engine block to combat this (there’s also a roller tensioner, externally adjustable, at the back of the block, the two items conspiring to virtually cancel potential cam chain disasters), but a good deal of mesh-gnash comes through. However, most of these noises are very businesslike and thus not particularly offensive provided you like the sound of well-organized machinery in action.

Three 32mm Dellorto carbs equipped with accelerator pumps feed the Triple effectively enough that you can manage to light it up without using the choke. We

mention this because the choke lever is carefully hidden on the left side of the bike, a bit below the oil cooler. If you remember where you left the choke, you’ll find the big Triple an excellent starter, with hardly a trace of the cold-bloodedness that plagues some of the zzzap-zzzap Fours. This is thanks in no small measure to the use of a Bosch electrical system featuring an alternator in combination with a magneto-supplied capacitive discharge ignition. This arrangement means you can get the Jota going even if the battery is almost flat. Unfortunately, a flat battery also means bump-starting, since a kick starter isn’t part of the Jota’s inventory.

As you might expect of a flat-crank Triple, the Laverda 1000 produces a certain amount of vibration. It’s unreasonable to compare it to the hairy Fours, because the beasts are so different, but even in league with other Triples, such as Yamaha’s XS750, it comes off as being quite thumpy. One of our riders claimed he could feel every power pulse, even with the tach soaring up toward redline. But others looked on this phenomenon as being another integral part of the Jota experience, like the exhaust note. The feeling of elemental power was somehow more pronounced than in the maniacal rush of a big Kawasaki, in any case the engine was comfortably smooth from 3000 rpm on up.

The other commodity delivered by this mastodon is power—lots of it. The wheel dyno at Pomona, California-based Rickey Racer, (West Coast distributor for Laverda during the year-and-a-half the company had no nationwide organization) regularly indicates 70 to 76 hp from new Jotas. Whew! That’s a lot of horsepower getting to the rear wheel (via a triplex chain to the 5-speed transmission and a #530 drive chain from there), and the nice part is the Laverda begins generating gobs of horsepower and torque well down in the rev range. It’ll pull from as low as 1500 rpm, and leaps forward eagerly when you crack the throttle anywhere from 3000 on up. It won't rev like the super duper Fours, but it does have excellent throttle response and it’s far from being reluctant. It’s simply a matter of a different style.

With gearing aimed at producing other worldly top speeds and a certain rastiness in its low end performance, our Jota didn’t figure to out hustle the KZ 1000 at the drag strip, and it didn’t. Times were in the mid12s, but by the end of each quarter the Jota was just beginning to come on. The gearbox, which is fashioned of the same uncompromising alloy as the rest of the engine, isn't set up for drag racing in any case. Shifting is a very deliberate business, particularly in the lower gears, and trying to hurry it means missing a shift. Our test bike came with its native right-side shift, left-side foot brake arrangement still in-

tact, rather than the cobbled up crossover linkage that satisfies Uncle Sam. The original arrangement is much better than the Heim-jointed crossover, but it’s still stiff and heavy; ride the Jota more than 100 miles in an outing and your toes will be filing complaints with your Intra-mural Cruel and Unusual Board at rapidly decreasing intervals.

The engine and transmission ride inside a fairly ordinary double-cradle backbonestyle frame that differs from the standard Laverda 1000 frame in having two additional members in the rear subframe, presumably for more structural rigidity. Although this traditional setup is becoming somewhat dated in the hippest road racing circles, it’s still viable in the Jota. Besides a great deal of back road barnstorming, we spent a day wringing the Jota out on the demanding curves and bumps of Willow Springs Raceway and the extraheavy backbone tubing didn’t show us much in the way of flex.

The suspension is home-grown Ceriani, fore and aft. Again, the emphasis is on heavy duty, with massive 38mm stanchion tubes up front. The double seals on these no-flex units virtually insure that the Laverda’s front suspension will simply ignore small bumps, at least through the first 1000 miles or so. This makes the bike an indifferent freeway companion, unless you know some stretches of freeway where you can go 120 mph or so without winding up in the slammer. The setup is best on macadam surfaces, and works most efficiently when the bike is moving rapidly. The rear shocks and springs are also fairly stiff and offer three preload selections, easily varied by using the adjustment levers cast onto the collars.

Big forged aluminum triple clamps help in maintaining front end rigidity. They’re>

JOTA ORIGINS

First of all, you’re probably wondering who this guy Jota was, and why did they name a motorcycle for him. That’s what we wondered, at any rate. It turns out the Jota in question is a traditional courtship dance and that its origins are Spanish— Aragonese, to be specific—not Italian.

Moto Laverda itself is headquartered in the town of Breganze, Vicenza province, northern Italy.

Laverda has recently appointed a new U.S. distributor, Yankee Accessory Corporation, PO. Box 36, Schenectady, N.Y. 12301. Rickey Racer—444A E. Monterey, Pomona, Calif. 91767—will continue as a Laverda dealership after serving as one of two de-facto distributors during the past 18 months. The other, Roger Edmondston, has sold out his Georgia-based operation to Yankee Corporation.

Besides buyers, Yankee is inviting Laverda dealer inquiries.

LAVERDA JOTA 1000

$4495

topped off by tricky adjustable handlebars featuring two toothed joints per side. In theory, this allows you to select any position you want, but in practice the master cylinder limits you to just a few choices, most of them uncomfortable for any extended use. The hard rubber grips compound tne discomfort.

Instrumentation, by Nippon Denso, is excellent, and the various control switches are nicely located. A particularly useful item is a European-style headlight flasher, and the Bosch H4 quartz-halogen lamp, the same unit that’s employed on big BMWs, is very difficult to ignore. It’s easily visible by day and illuminates enough highway to allow high speed cruising by night. The lamp is held in place only by a snap-on chrome collar, and hides all the bike’s circuitry—the essentials of which are dual, to cover for possible shorts—inside the headlamp shell.

The single rear view mirror drew praise from our art director as being the best looking one he’s ever seen, and it affords a dandy view of the rider’s left armpit. About the qnly way to get any view of what’s going on behind you is by raising your left elbow, and even then the vista is pretty limited. A grip-end mirror would be better. Failing that, perhaps a chiropractor can help you get an extra inch of lateral travel into your neck. You’d better be able to see rearward somehow if you’re going to fly this rocket on public roads. It’s an attention-getting device if ever there was one.

As we’ve mentioned, once it gets up to thoroughly illegal speeds the Jota is as stable and predictable as the West German economy. However, at around-town velocities the steering feels uncomfortably heavy. The first impression is of excessive bulk, which is reinforced by the massive-^ ness of various components. But this is deceptive: At 525 lb. (with a half-tank of gas) the Jota is 29 lb. lighter than the KZ1000. The steering heaviness is thus attributable to a combination of a moderately high center of gravity (the DOHC Triple is inclined slightly from vertical, but is nevertheless quite tall; narrow handlebars; and 4.5 in. of front wheel trail.

Stopping ought to be a prime consideration in any superbike, and the Jota stands near the front of the class in this department with three Brembo dual-piston calipers squeezing down on cast-iron rotors. The cast iron doesn’t stay as pretty as units with higher percentages of stainless steel, but it provides stop after fast, positive, fade-free stop. The front brakes—10.8-in. each—provide the bulk of the stopping force. The 10.9-in. rear disc requires a great deal of pedal effort, and isn’t particularly distinguished on its own. It requires real concentration to lock it up, however.

continued on page 90

continued from page 45

The five-spoke cast alloy wheels are manufactured by Laverda, and feature their own built-in counterweights opposite the valve stem. They are good looking but a bitch to clean. Our Jota was fitted with Dunlop K8l tires, which provided plenty of stick in all kinds of going. We'd say these are the ideal, but it may be that future Jotas will arrive wearing Pirellis.

Rider comfort isn’t a particularly strong suit with the big Laverdas. Besides the narrow cafe-style bars, which keep the pilot crouched low over the big (5.4-gal.) tank, the footpegs force one’s knees up toward a position that’s almost semi-fetal. We conclude that most Italian riders are built along the lines of the orangutan, and that rearsets would be most helpful for those of us proportioned more conventionally. The seat is firm but comfortable, and there's plenty of room to go two up although this activity isn't much fun around town as it compounds the Laverda’s tendency to want to fall over in slow going.

However, it's nice to have someone along when it comes time to heave this rocket up onto its centerstand. A simple heave-ho won’t suffice—it takes a long and determined pull, carefully coordinated with just the right pressure on the centerstand’s side lever. Also, the spot for centerstanding must be carefully chosen. If it's anything other than dead level, the Laverda will tumble to earth with a mighty crash. This happened to us during one photo session, snapping off the front brake lever and right-side turn signal. A sidestand would be a welcome addition to the Jota's equipment.

Cosmetically, the bike speaks for itself. It’s hard to imagine the Jota looking any more purposeful or lean-and-mean. The front fender bracing is perhaps too agricultural. and a three-eighths fairing of some sort would enhance the overall effect, but all-in-all the Jota's looks say road wrinkler. and that’s truth in packaging all the way. The Jota’s silver paint isn't as attractive as the racing red on the regular 1000, but it really doesn't hurt to have this little touch of invisibility. You'll welcome it when you begin comparing your upper limits against the Laverda's, a pastime that’s certain to irritate your local law enforcement society.

We come at last to the reckoning. The Laverda Jota 1000 lists for $4495. By the time you get through with various taxes, prep and destination numbers, you're eyeball-to-eyeball with five Gs for a machine whose sole function, if we’re going to be honest, is escape. No matter what they do to you out there in the day-to-day jungle, you know at the end of the day you can wrap yourself around the Jota and fly away into another realm. Who can put a price on that kind of therapy? 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSelling the Sizzle

November 1977 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsService

November 1977 By Len Vucci -

Features

FeaturesToo Much Government Is In Our Future

November 1977 By Lane Campbell -

Features

FeaturesItalian Spoken Here

November 1977 By Jean Crabb -

Roundup

RoundupThe Victory Continues

November 1977