Souping the 650 Seca

How To Make A Used Yamaha 650 As Fast (And As Expensive) As A 750.

John Ulrich

Motorcycle technology is a two-sided coin. Better and faster and quicker motorcycles are good; having a perfectly-good motorcycle made obsolete by a new, better, faster and quicker machine is not so good.

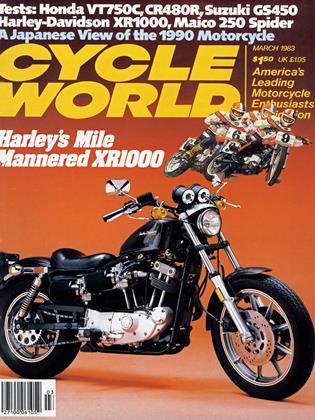

The Seca 650 is a case in point. Tested in the April 1982 issue of Cycle World, the 1982 Seca 650 made enough power to be the quickest and fastest 650 at the dragstrip, turning the quarter mile in 12.78 sec. with a terminal speed of 103.68 mph.

But those figures, perfectly respectable in April of last year, pale beside the shattering performance of the 1983 Honda Nighthawk 650, which blitzes down the quarter mile in 12.13 sec. with a terminal speed of 108.43 mph.

That might not bother some riders, but others, with a penchant for high performance, might bristle at the thought of a bike with cruiser styling blowing away their sporty Seca in any measure of performance. We’re talking about the Seca and Nighthawk here, but it just as well could be any two motorcycles, one a year or two old, the other the latest, trickest thing out of Japan this month. The problem— and answers—apply to many machines.

Short of trading in on an 1100, what’s a motorcyclist to do?

Get more power.

Lots more power. From pistons. Camshafts. Exhaust systems. Carburetors.

The parts are out there, a dazzling array of pieces with outrageous claims attached, all guaranteed to boost power without sacrificing powerband or reliability.

The easy thing would be to drop the Seca off at some house of high performance, order up the works, come back two weeks later and ride off into the sunset, the Seca vindicated and powerful and ready to face down the latest invaders.

But while that’s the easy way, it’s usually not the way it actually happens. A rider buys a set of pistons, a pipe, maybe some cams, and installs them himself.

Which is what we decided to do.

Lingering around the office as a longterm test bike, our Seca 650 had, in the course of being thrashed to within an inch of its life on a regular basis, become somewhat slower than when first tested.

In stock condition, the bike managed only 13.39 sec. and 98.90 mph at the dragstrip with about 5500 mi. on the odometer.

The Seca needed serious help.

We started its rejuvenation with a set of 68mm pressure-cast, three-ring Yoshimura pistons, which increased displacement from 653cc to 761cc and compression ratio from 9.2:1 to 9.5:1.

It wasn’t cheap. Yoshimura piston kits have a reputation for reliability and long life but are expensive, $275 a set including wrist pins, circlips, rings and a new head gasket.

The stock 63mm cylinder liners can’t accommodate a 5mm bore increase, which means that the stock liners must be pressed out, the aluminum cylinder block bored to accept larger liners, the larger liners pressed into the block, and the liners bored to accept the larger pistons.

Yoshimura R&D of America charges $25 per cylinder to remove stock liners, bore the cylinder block, press in new liners and deck the head gasket surface. Boring the new liners to fit the pistons costs another $25 per cylinder, or a total of $200 labor. The new cylinder liners are $34 each, or $136 for the set of four. So, preparing the Seca’s cylinder block for the big-bore kit cost $336, which, added to the piston kit, totals $611.

Not cheap.

To see how Yoshimura’s prices compared, we called a local machine shop (Q&E Machine, 1140-A N. Kraemer Blvd., Anaheim, Calif. 92806, 714/6305720) and asked for their prices. Q&E charges $30 to remove all four liners, install all four new liners and deck the cylinder gasket surface; $15 a hole to bore cylinders for oversized liners; and $20 a hole to bore liners to match pistons. At those prices, labor for cylinder preparation would total $170. Q&E also sells liners for $30 each, or $120 for four. Total cylinder prep at Q&E’s prices would be $290, and adding the piston kit would total $565.

Still not cheap.

Because the bike was apart anyway, we decided a valve job would be a good idea. Yoshimura charges $140 for a racing valve job, and we signed up. Both block and head were ready about one week after they were delivered to Yoshimura R&D of America, 4555 Carter Ct.,Chino,CA 91710,(714)628-4722.

Along with the racing valve job we ordered a set of Yoshimura racing valve springs and aluminum retainers, the valve springs because stock Japanese valve springs usually sack significantly after a few thousand miles, the aluminum retainers because they come with the valve springs and are lighter than stock parts, reducing the chance of valve float at high rpm with radical camshafts. The set of springs and retainers cost $75.

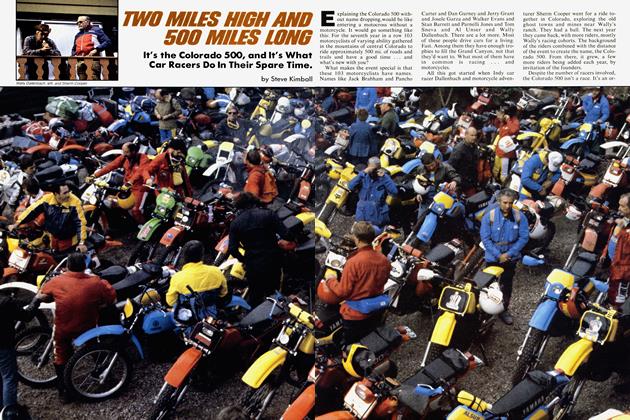

After installing the new parts (and after several hundred miles of break-in) we took the Yamaha back to the dragstrip. With the stock exhaust system, stock Hitachi CV carburetors, stock airbox, air filter and camshafts, the Seca was much faster. Four passes produced times ranging from 12.66 sec.at 106.13 mph to 12.53 sec. at 106.76 mph, each pass slightly quicker and faster than the one before. The Seca’s powerband was much improved, the bike pulling very well from 3000 rpm to 9000 rpm. The bike would rev to 10,000 rpm, but the best results came with shifts at or slightly below 9000 rpm. Best power was produced over 5000 rpm.

The addition of the big bore kit made the Seca 650 about 0.25 sec. quicker than its best stock pass and about 0.86 sec. quicker than it ran in stock condition after 5500 hard miles. Terminal speed went up 3.08 mph from the Seca’s best and 7.86 mph from the post-5500-mile terminal.

The difference was easily felt on the street—the Seca 650 didn’t need as much throttle nor as many revs to leave a stop, and accelerating quickly wasn’t as frantic, requiring fewer shifts and less effort to find power.

We were going in the right direction, and having found success, wanted more.

More power.

The next step was logical enoughadd Yoshimura camshafts ($230) and 4into-1 exhaust system ($195 in black, $210 in chrome).

The camshafts recommended by Yoshimura for the Seca 650 are called Stage II YA-101 cams with 10.4mm intake lift (stock is 8.5mm) and 9.7mm exhaust lift (stock is 7.8mm). The Yoshimura camshafts open the intake valves 28° BTDC and close the intake valves 65° ABDC, opening the exhaust valves 59° BBDC and closing the exhaust valves 29° ATDC.

The stock camshafts open and close the intake valves 34-58° and open and close the exhaust valves 66-26° when measured, like the Yoshimura camshafts, from and to 0.020 in. lift.

The Yoshimura cams were designed for the Seca 750, which, unlike the Seca 650, has an electronic tachometer. Which meant there were no gears on the cam to mesh with the 650’s tach drive. The camshaft did have the shoulder from which gears are normally cut, and that shoulder wouldn’t clear the tach drive, which thus had to be removed. That left a gaping hole—the tach drive bore—in the cylinder head.

Fortunately the Seca 650’s tach drive is the same diameter as the 1982 Suzuki GS1100’s tach drive. Because the 1982 GS1100 has a mechanical tach and the 1982 GS1000S Katana, using a virtually identical engine with smaller bore, has an electronic tach, there is a Suzuki tach drive bore plug available for the Katana, part number 26442-45000, $4.47 retail. It fits the Seca perfectly.

Which left the problem of reading engine rpm, since the stock mechanical tach couldn’t be used. The electronic tach from a Yamaha XV920RH is the same size, although the faceplate redline starts at 7000 rpm, and bolts right into the Seca’s instrument cluster. It took several wiring connectors to make the electronic tach work, with most of the connections made to wire junctions found inside the headlight shell. We fitted male connectors to the tach’s black and brown leads, and plugged black into ground and brown into positive. The tach’s blue lead came with a male connector attached and plugged into the instrument lights loom. We attached the tach’s orange lead to the ground side of the left coil.

The tach, part number 5H1-83540-00, retails for $137.45 from Yamaha dealers, but might be available from a motorcycle salvage yard for less.

Yoshimura recommended larger jets for the stock 32mm Hitachi CV carburetors, but Hitachi parts are not readily available at motorcycle dealerships. Because larger Hitachi jets were not available, Yoshimura mechanics gave us a set of drilled main and pilot jets. They selected the drill size by looking through a drill index to find a bit the same size as the stock jet opening, and drilled the jet with the next larger bit.

With all the parts installed, the Seca would not accept more than half throttle below 8000 rpm, but pulled strongly from 8000 to 10,000 rpm. On the street the bike was generally useless, sputtering and bogging at any attempt to accelerate quickly from engine speeds below 8000 rpm.

We gave the engine a leak-down test, in which compressed air is blown into a cylinder, at TDC, and the volume lost past the rings and valve seats measured as a percent. Each cylinder uniformly tested to an 8.0 percent leakdown loss, showing rings and valve seats to be in good shape.

Since the leakdown test results were good and the parts installed correctly, we took the Seca to the dragstrip, where, since engine speeds are kept high throughout a run, the problem might not show up.

The Seca’s best pass in seven runs produced an E.T. of 12.03 sec. with a terminal speed of 110.42 mph. Two runs were aborted because the bike bogged at the shift into second gear, when rpm fell below 8000. The last two passes were made with the baffle removed from the Yoshimura pipe, producing E.T.s of 12.14 and 12.19 sec. with identical terminal speeds of 110.29 mph.

This trip to the drags proved that good quarter-mile results don’t necessarily relate to good street performance, and that removing the baffle from a Yoshimura pipe doesn’t necessarily increase performance. Each ride up the return road after a pass reaffirmed that the Seca, at any rpm below 8000, ran terribly.

Back from the strip, we installed a Maxi-X 4-into-l-into-2 exhaust system ($249.95 in black or chrome from MaxiProducts, 9271 Archibald Ave., Cucamonga, Calif. 91730, 714 /987-

2313). The Maxi-X routes the four head pipes into a flat collector which leads into two small megaphones. Like the Yoshimura pipe, the Maxi-X requires centerstand removal. Unlike the Yoshimura 4-into-l, the Maxi-X system’s head pipes slip into the collector and are not welded in place. That allows the head pipes to move around and snag on cylinder head exhaust studs during installation, making it harder to fit.

The Maxi-X exhaust system did not clear the Seca’s centerstand support brackets, which must be trimmed with a grinder or hacksaw. When we asked about the clearance problem, Monty Campbell of Maxi-Products said that later production examples have the megaphones positioned at a slightly different angle, increasing clearance at the centerstand support bracket and eliminating the need to trim the bracket, but reducing available cornering clearance. Campbell traded our early system for one of the latest Maxi-X systems, which we installed on the Seca without changing carburetor jetting.

The results were dramatic. With the Maxi-X, the Seca would accelerate from 3000 rpm at full throttle, stutter between 5000 and 6000 rpm, and accelerate hard from 6000 to 10,000 rpm. The flat spot between 5000 and 6000 rpm didn’t show up at less than full throttle and the Seca could be ridden normally on the street.

Our next step was to attempt to tune out the flat spot by changing carburetor jets. Experimenting, we found that standard slot-head Mikuni main jets, as used in 29mm and33mm Mikuni Smoothbore carburetors, fit Hitachi carbs. The Mikuni jets are not as refined as the Hitachi jets, which feature a tapered orifice designed to promote high velocity fuel flow, but having the right jet size is more important than having the optimum jet orifice taper.

It’s important to note, however, that Hitachi jet numbers don’t correspond to Mikuni jet numbers. For example, after drilling by Yoshimura mechanics, the 110 Hitachi main jets were the equivalent of 107.5 Mikuni jets.

Trial and error showed that raising and lowering the carburetor needles had no effect on the 5000-6000 rpm flat spot. Installing smaller (105 Mikuni) main jets reduced the severity of the stumble and shortened its duration, but also decreased full-throttle acceleration above 6000 rpm.

Efforts to change the pilot jet circuits were frustrated by the non-availability of Hitachi pilot jets and the fact that Mikuni and Keihin pilot jets won’t fit Hitachi carbs. We were at a dead end.

Until we started thinking about replacement carburetors. Smoothbore Mikunis were out of the question—their spacing doesn’t match the Seca’s ports. But the Seca’s bore spacing is almost identical to the bore spacing of a sohc, pre-1979 Honda CB750. It happened that Campbell had a set of stock 28mm Keihin slide-throttle carbs, with accelerator pumps, from a 1978 CB750F.

To make the Keihin carbs clear the Seca’s alternator we ground off the floatbowl drain hose fittings on the carbs for cylinders one, two and three. That done, the carbs slid into the stock Seca rubber manifold boots. The stock Seca manifold clamps each have two tabs sticking straight up from the top of clamp—the tabs fit around a protrusion on each stock carb and keep the clamp centered and its tightening screw easily accessible. The tabs get in the way when using Keihins, so we bent the tabs flat.

The rubber boots connecting the stock Seca carbs to the airbox also fit on the Keihin carbs, although the boots were loose on the rear of the carbs. We used hardware-store hose clamps to tighten up the boots around the carburetors.

Because the Keihin carbs are shorter than the stock Hitachi carbs, the Seca’s carb boots, when attached to the Keihins, don’t reach as far into the airbox, but still provide a good seal. The Seca’s choke cable hooked up to the Keihin choke lever, but the handlebarmounted choke control didn’t have enough throw to fully engage the choke. We increased the lever travel by shortening the choke cable housing with a grinder and by taking apart the choke control housing and grinding away a travel-limiting stop. That left just one problem—the idle adjustment knob on the carburetor linkage hit a protruding gas tank seam at about one-fourth throttle. We used a pair of pliers to bend the seam out of the way.

With 102.5 main jets, the Keihin carbs reduced the Seca’s flat spot to a slight miss at full throttle between 5000 and 5500 rpm.

We headed back to the dragstrip and made 10 passes, four runs with the MaxiX, four with the Yoshimura exhaust, and two with stock exhaust. The bike’s best pass with the Maxi-X produced an E.T. of 12.15 sec. and a terminal speed of 109.22 mph. The best pass with the Yoshimura pipe was 12.08 sec. at 109.48 mph. With stock pipes the Seca ran 12.36 sec. and 106.88 mph.

With the Keihin carbs, the Seca ran as well at low rpm with the Yoshimura pipe as it did with the Maxi-X. With both pipes the bike had a momentary misfire between 5000 and 5500 rpm. The Seca had no flat spot anywhere in the rpm range with the stock pipes.

The inside of each set of pipes was black, indicating a rich mixture, so we installed smaller, 97.5 main jets before making another 10 runs. This time the Seca ran 11.98 sec. and 110.15 mph with the Maxi-X and the flat spot had disappeared. Throttle response was perfect at all rpm, and best power kicked in above 6000 rpm.

With the Yoshimura pipe, the Seca ran 11.99 sec. and 110.97 mph, and again the flat spot had disappeared. Best power was still above 6000 rpm. With stock pipes, the Seca had a best E.T. of 12.18 sec. with a terminal speed of 108.69 mph.

Impressed by the results, Campbell decided to sell cleaned, inspected and jetted Keihin slide-throttle carburetors for Yamaha Secas and Maxims, with the float-bowl drains trimmed and ready for installation. Campbell has a limited supply of 28mm carbs available for $200 a set through Maxi-Products.

That done, we can summarize our findings as follows:

—The Seca was quicker and faster after we installed a Yoshimura big-bore kit, racing valve job, heavy-duty valve springs and aluminum spring retainers. With stock Hitachi CV carburetors, stock airbox and air cleaner, stock exhaust system and stock camshafts, the Seca ran 12.52 sec. at 106.76 mph with perfect throttle response and more lowend, mid-range and high-rpm power.

—The Seca ran very poorly, misfiring and stuttering below 8000 rpm, when we added Yoshimura high-lift camshafts and a Yoshimura exhaust system to the parts listed above, using stock Hitachi carburetors with drilled main and pilot jets.

—The Seca ran well from 30Ó0-5000 rpm and from 6000-10,000 rpm but misfired at full throttle between 5000 and 6000 rpm when we substituted a Maxi-X exhaust system for the Yoshimura exhaust system. Attempts to re-jet the Hitachi carbs with available parts failed to remove the 5000-6000 rpm flat spot without sacrificing significant top-end power.

—The Seca ran perfectly, started easily when cold, and was fastest and quickest when we replaced the Hitachi CV carbs with a set of properly-jetted 28mm Keihin slide-throttle carburetors, no matter which of the three exhaust systems was used. The Keihin’s only flaw is heavy throttle springs, which we are going to fix. The stock exhaust system produced the best low-end and mid-range power. The Maxi-X and Yoshimura exhaust systems made less low-end and mid-range power but dramatically increased high-rpm horsepower. The Seca rin 11.98 sec. and 110.15 mph with the 4axi-X exhaust, 11.99 sec. and 110.97 ii.ph with the Yoshimura exhaust, and 12.18 sec. and 108.69 mph with the stock exhaust system. Both the Maxi-X and the Yoshimura exhaust systems were far louder than stock, reading 91 db(A) (Maxi-X) and 93 db(A) (Yoshimura) in standard noise tests. The stock exhaust read 82 db(A) in the same test.

There is a choice here. The Maxi-X and Yoshimura systems produced more power but made more noise, drawing more attention on the street from both friend and foe.

Our sound test ended, as luck would have it, with the stock exhaust system in place. Tested in April of last year, the Seca 650 delivered 48 mpg on the Cycle World mileage test loop, and we wondered what effect our modifications had on fuel economy. After two laps of the 50-mile test loop we had our answer: the hopped-up 761cc Seca got 46 mpg with stock exhaust.

In that form, the Seca made enough power to face off against the latest highperformance 650s and 750s. The transformation from 13.39 sec. and 98.90 mph to 12.18 sec. and 108.69 mph cost $1116. That’s $91.48 per 0.10 sec. and $114 per 1.0 mph.

Performance, it seems, is never cheap. But if you’ve got to have it, no price is too high.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFor Adults Only

March 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1983 -

Book Review

Book ReviewVincent Vee Twins

March 1983 By AG -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

March 1983 By James F. Quinn -

Features

FeaturesTwo Miles High And 500 Miles Long

March 1983 By Steve Kimball -

Features

FeaturesLearn Fast, Learn Hard

March 1983 By John Ulrich