JOCKEYING FOR NUMBERS

Drag strip elapsed time, otherwise known as the original E.T., has in recent years become a yardstick of motorcycle performance. At first E.T. was reserved for those who spoke drag racing jargon. Then, because numbers are easily explained and understood, the magazines began listing strip performance right along with top speed and miles per hour, because everybody who'd been to the drags knew what the letters meant and everybody who cared about performance had been to the drag strip.

Then came Superbikes, the asphalt wrinklers that outdid any car you’d meet at any stoplight and which began outdoing each other, at the strip and in the showroom. E.T. became part of motorcycle marketing and people began to wonder; why do the ads give performance times, why are all the tests different, what do they mean and have any of these figures any relationship with what the buyer gets?

Yes and no.

In different ways. The difference between an E.T. of 11.01 sec. and 10.90 sec. is a speck of time not perceivable by the average person. But in sales technique, and perhaps to the man who buys only the quickest, the difference between an 11-sec. bike and a 10-sec. bike is a Grand Canyon.

Which brings us to a different sort of drag strip test.

Even with the same bike (and especially with some of the hotter bikes) E.T. can vary almost infinitely. There's preparation. There’s drag strip condition, and weather.

But most of all, there's rider skill, and experience . . . and weight. E.T. measures how long it takes an engine to move an object a specific distance. Given the same horsepower, obviously moving a heavier object takes more time.

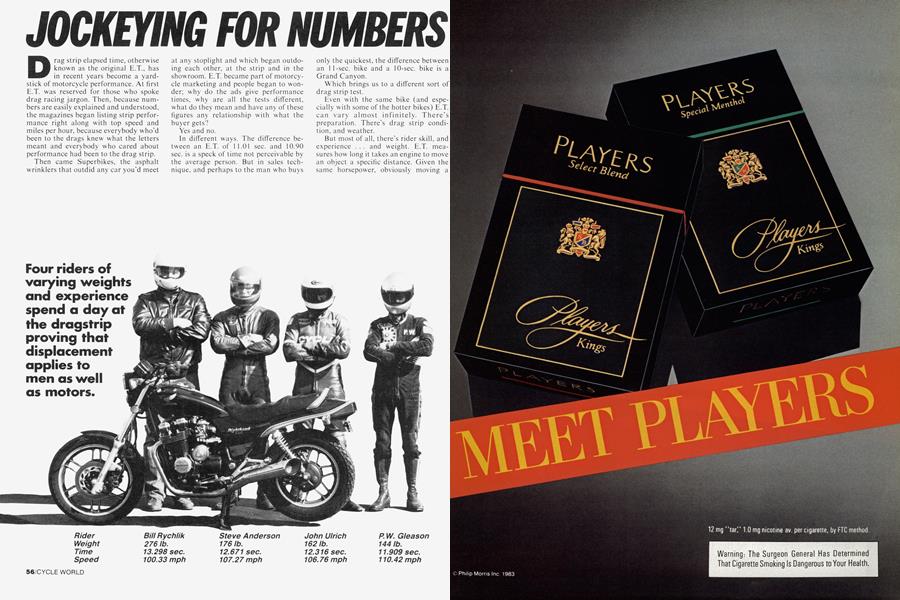

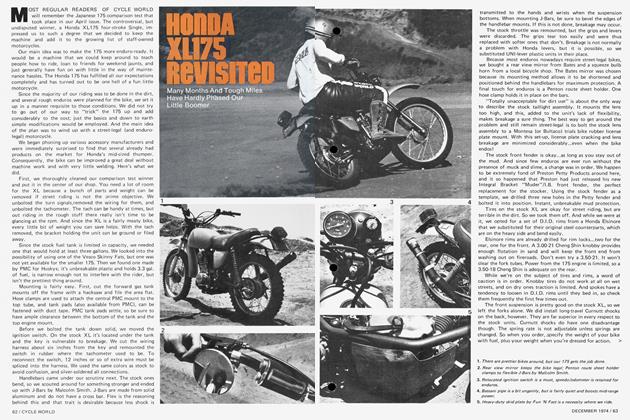

Four riders of varying weights and experience spend a day at the dragstrip proving that displacement applies to men as well as motors.

Rider Weight Time Speed

Bill Ryehlik 276 lb. 13.298 sec. 100.33 mph

Steve Anderson 1761b. 12.671 sec. 107.27 mph

John Ulrich 162 lb. 12.316 sec. 106.76 mph

P.W. Gleason 144 lb. 11.909 sec. 110.42 mph

To demonstrate, we lined up four riders. By no random chance, they varied in drag strip experience and in weight. By luck, both scales moved in the same direction, that is, the best and most experienced rider weighed the least, and the least experienced weighed the most.

All four rode the same bike on the same day. To keep things otherwise equal we needed a median performance motorcycle, one that would challenge the best yet not intimidate or overwhelm the novice (and one that would illustrate the meaning of power to weight).

Our pick, a 1983 Honda Nighthawk 650, was the star of the show, having already survived 2832 hard miles. It had been to the drag strip before, during testing for the February issue, and had turned the quarter in 1 2. 1 3 sec. with a terminal speed of 108.43 mph. That session had made the clutch grabby, and the bike was difficult to launch and prone to wheelie in fast starts. The Nighthawk has hydraulic valve lash adjusters which pump down if the bike is over-revved, reducing the chances of bent valves caused by a missed shift. (That proved to be an important feature.)

The riders included:

-P.W. Gleason, 27. Gleason's ability to wring quick times out of street motor cycles has landed him work for most of the Japanese manufacturers, and he has appeared in dozens of magazine and tele vision advertisements. Gleason began racing at age 10 and has competed in professional expert dirt track, road race and drag races. He calculates that in one recent three-year period he made over 6000 drag strip passes in testing and racing.

His value can best be appreciated by a racing story: At the 1979 NHRA Winston World Finals Gleason and a 1200cc, gas-burning Kawasaki 1-bur won the Top Fuel class, beating Russ Collins and his 2000cc nitro-burning Honda V-8. Gleason's winning E.T. was 8.42 sec. while Collins lost with an 8. 11.

You read that right. Not only did Gleason win with less power, he won with a slower time. He did it because he was so good at timing the lights and so quick at getting the bike launched, that his riding skill made up for an 0.3-sec. deficiency.

Gleason is good. On our certified scale, in test trim, i.e. boots, leathers, gloves and helmet, he weighed 144 lb.

—John Ulrich, 29. He began with enduros and street riding 14 years ago. John's been road racing for eight years and he wins his share.

But for our purposes here, John's advantage is time at the drag strip. For consistency's sake, the magazine's policy is to have the same rider for all test bikes, so during the past five years Ulrich has made more than 1000 passes on 175 dif ferent motorcycles, ranging from small stockers to a Top Fueler. And during this time he's taken lessons from pros like Terry Vance and Jim Bernard. Euuipred, John weighed in at 162 lb.

-Steve Anderson, 28. Steve is Tech nical Editor. He's also the back-up man at the test track, so he's been going to the drag strip once or twice a month for the past nine months. He's been a street rider for eight years, and runs club road races but he'd have to be considered a novice drag racer. With gear, Anderson weighed 176 lb.

-Bill Rychlik, 40, service manager for Champion Motorcycles. A street rider for 1 5 years, Rychlik raced district level dirt track for three years and, after retiring from racing, he prepared race bikes for 1 3 years, most recently for motorcrosser Rex Staten. Rvchlik had never been on a drag strip before our test session. Rychlik tipped our scales at 276 lb. with gear.

Four riders, none of them beginners, all with lots of hours on motorcycles but varying degrees of drag strip experience. All ready to ride the same motorcycle under the same conditions at the same drag strip on the same day.

Those four "sames" are important. E.T. is not as simple as it may seem. It is, by definition, the time a motorcycle re quires to accelerate from a standstill to a point 1320 ft., one quarter mile, distant. The time is measured by computerized clocks triggered by light beams at each end of the strip. A motorcycle at the starting line breaks a light beam with its front wheel. When the run starts, the bike's front wheel moves out of the light beam and the clocks are activated. When the bike's front wheel breaks another light beam at the end of the measure quarter-mile, the clocks stop, and the re sults are displayed on a digital clock reading to three decimal places.

That elapsed time is not absolute, though. Rider weight and skill affect E.T. and so do conditions at the drag strip. The morning after an organized drag race, the starting lanes are coated with sticky rubber, making for good launches. Wipe some of this off with a hard rain and bikes may spin the rear tires when accelerating hard. Air density affects horsepower, which naturally affects drag strip times. When air is hot or humid, or the elevation is high, air density and horsepower go down. Our best runs are made early in the morning after an organized meet. And if winds come up and the day gets hot, the conditions change. And then there is the question of machine oreoaration.

The bikes Cycle World tests are provided by the manufacturers as representative samples of the model, in theory being just like the ones you can buy off the showroom floor. We take the bikes to the drag strip to get an idea of what a buyer can expect under good conditions and to see how performance compares with other motorcycles. As much as possible, all our drag strip acceleration tests are conducted by one staff member, eliminating rider variables, and the bikes are run as delivered, without special set-up to improve E.T.

Manufacturers, on the other hand, want the best possible results as a sales tool. It's not uncommon to see a professional drag racer and a crew' from a manufacturer at the strip two or three days in a row, making adjustments and running and fiddling until a desired E.T. is reached. To get those quick times, motorcycles have been run with a vacuum in the forks (the front end compressed and the valve stems depressed to bleed off air), 50 psi in the front tire, 16 psi in the rear tire, advanced timing, race gas in the tank, whatever it takes to control wheelies, reduce friction, increase traction, squeeze out a little more horsepower. The best time often ends up in advertisements for that particular motorcycle.

Most of the drag times you read about in advertisements and road tests come from sessions at Orange County International Raceway in Irvine, although sometimes manufacturers will run at Fremont Raceway, which is often 0.1 or 0.2 sec. quicker due to better traction and atmospheric conditions. We do all our testing at Orange County.

Which brings us back to the dragstrip with our Nighthawk and four riders. Each man would make two sets of three passes. Gleason went first, doing a short burnout to heat the rear tire and then quickly staging before each run. He spun the rear tire on his first and third passes, missed a shift on his first pass, and wheelied in first gear during his second, and quickest pass, turning 12.193 at 109.62 mph.

Every motion Gleason made was done for a reason. None were wasted. Shifts were made with the throttle held wide open, the clutch just touched for an instant as the lever was jammed upward. After leaving the lights Gleason crouched as low as possible, getting out of the airstream, his left hand tightly tucked into the side of the bike.

Ulrich was next. Before making any passes he rode the bike slowly down the strip and back, at 2500 rpm in sixth gear, to cool the engine and clutch. Then he did long burnouts before staging, and launched at 10,000 rpm, slipping the clutch. The bike wheelied off the line on each of his three passes, so he had to click the throttle back slightly to get the front wheel down each time. His second pass had more clutch slip and less wheelie, and he turned 12.316 sec. at 106.76 mph.

Anderson followed, also making a slow cool-off trip down the strip before starting his passes. He had trouble with burnouts, because he’d seen them done but never actually tried it for himself. He didn’t know to stand up and lean forward, unloading the rear tire, so instead of smoking and spinning the tire he lurched forward against the front brake.

The Nighthawk isn’t the easiest bike to ride. Anderson didn't have enough revs for his first three runs and bogged the engine each time, plus missing the 12 shift twice. His best pass for the first session was 12.688 sec. and the trap speed wasn't recorded because we didn’t set the clocks right. (Speaking of expertise: at our usual test sessions the clocks are his job, which he does better than his stand-ins could do.)

Before Rychlik's runs, Gleason explained to him the purpose of the burnouts. They heat up the rear tire, giving it more traction. This is especially important on bikes prone to wheel spin, or in very cold weather when the bike is more likely to spin the rear tire. Because of his greater weight, Rychlik wouldn’t have any problem with wheel spin, Gleason explained, so a burnout wouldn’t be necessary. Lots of weight on top of a motorcycle makes it more likely to wheelie because the center of mass is higher.

In two of his first three runs Rychlik rolled out of the timing lights before starting, triggering the clocks and extending the E.T. The one time he didn’t break out of the light beam, he wheelied and spun the tire and missed the shift to second gear, turning 14.04 sec. at 97.61 mph.

In the next set of passes, Rychlik was up first, after some coaching on how the staging lights work. There is a range, a few inches long, where the bike will stage. You can tell a bike is staged when two yellow lights flash on at the top of the lights between the lanes. Because the clocks don't start counting until the front wheel Iras left this staging position, there’s a way to get a better time by staging correctly. By moving forward into the staging area to the spot where the lights just come on, the rider, in effect, gets to make a tiny running start. He takes off and moves the few inches where his front tire is still tripping the lights before the clocks start timing, saving a few hundreths of a second.

This time Rychlik did much better, wheelying on each pass but not missing any shifts and turning a best time of 13.298 sec. at 100.33 mph.

On his first pass of the second set Anderson missed second gear so severely,, that he aborted the run. He missed second gear again the next time, but caught every gehr -and wheelied in first for a 12.671 at 107.27 mph in his last pass.

continued on page 108

continued from page 61

Ulrich wheelied off the line in every one of his second-set passes and missed fourth gear three times in one run. The clutch was dragging during tho, powershifts everyone was making, leading to missed gears during attempts to shift at full throttle at the redline. Each missed shift sent the tach needle soaring, and it’s amazing that the NighthawU didn’t bend its valves. His best second-set time was 1 2.361 sec. at 106.38 mph.

Gleason didn't waste any time in making his final three passes. He jumped on the bike, did his burnout and staged, launching perfectly, holding full throttle, using the clutch to keep the front wheel about three inches off the pavement and powershifting, turning 1 1.909 at 1 10.42 mph. He backed that up with an 11.94? at 110.83 despite a wheelie at the start, and followed that with a 12.002 at 110.15 despite spinning the tire at the start of his third pass.

We were impressed.

“There’s no substitute for experience,” Gleason told us. “That’s what made me fast, lots of practice. I do bestwhen I take a short break and think* about it, and I learn something every pass I make, maybe do something just a little bit quicker or do something else a little faster.”

What kind of tricks does Gleason use to get those quick times? One example is something nobody noticed, although Gleason did it on every pass. He staged with his feet back near the rear axle, and w'edged his feet between the track and the mufflers, levering up with his toes to slightly unload the rear end. Doing that lets the tire spin the critical first 10 or 12 in. off the line, Gleason says, reducing any tendency to wheelie or bog, and also eliminating the lurch usually encountered when leaving the line on a driveshaft-equipped motorcycle.

At the end of the day there was onlyone small confusion. Anderson’s best run had a faster trap speed than did Ulrich’s best, although Ulrich’s E.T. was better (as it should have been for a lighter, more experienced rider.)

No problem. The difference between 106.76 and 107.27 mph is half an mph, not statistically vital. Anderson was spinning his wheel and we’ve often seen a worse E.T. and better trap speed result" from too much wheelspin. Something about stored energy, Mr. Engineer Anderson says.

Beyond that, we saw with our own eyes that the ad claims can be proven. Given time and preparation and a rider like Gleason, the factories can obtain amazing and impressive times without resorting to stroker cranks, slick tires and Downhill International Raceway.

This approach can be defended. We're speaking of motorcycle tests, not ridertests. Not even Pee Wee Gleason could get a stock bike to do more than it can do, so when the factory gives a drag strip time, they may be trying to influence, but they are not making things up.

But we're just as pleased with our own test procedures. Our tests are to inform, rather than influence. The test may report that the Brand D 500cc Twin is the quickest in its class but that’s only fact. We don't have a dime or a heartbeat investedin the test of any model, and we don't care if the Brand C 500 is quicker or slower than the Brand D 500.

What our test is supposed to do is tell the owner or prospective owner what he'd get if he bought the model under review. Our riders are good, they do their best and they have lots of time on track. But they aren't doing a thing any other motorcycle nut, given time and practice and some coaching and a machine in good condition, couldn't do.

Well, excepting maybe losing weight. Rychlik knows how to ride and tune. But no 276-lb. rider can expect to beat a 144lb. rider of equal skill no matter how much the big guy practices.

Speaking of skill, don't forget that timed tests aren’t races. At the actual drag meet there are two sets of lights. One tells the riders when they can start and the other tells them how long it took to cover the distance after they started. Our man Ulrich has turned better test times than Terry Vance, who is heavier than Ulrich. But Ulrich loses every race to Vance because Vance is the better drag racer.

Thus, while we can predict that a good rider on a fresh 650 Nighhawk can equal our times, this doesn’t mean that the Nighthawk owner may not lose to a slower bike ridden by a better rider.

All of which may mean that E.T. is most valuable when comparing motorcycles ridden by the same man, under the same conditions at the same track. There’s more to E.T. than numbers and getting low numbers isn't only a function of the motorcycle’s horsepower.

E.T. is E.T., nothing more and nothing less.