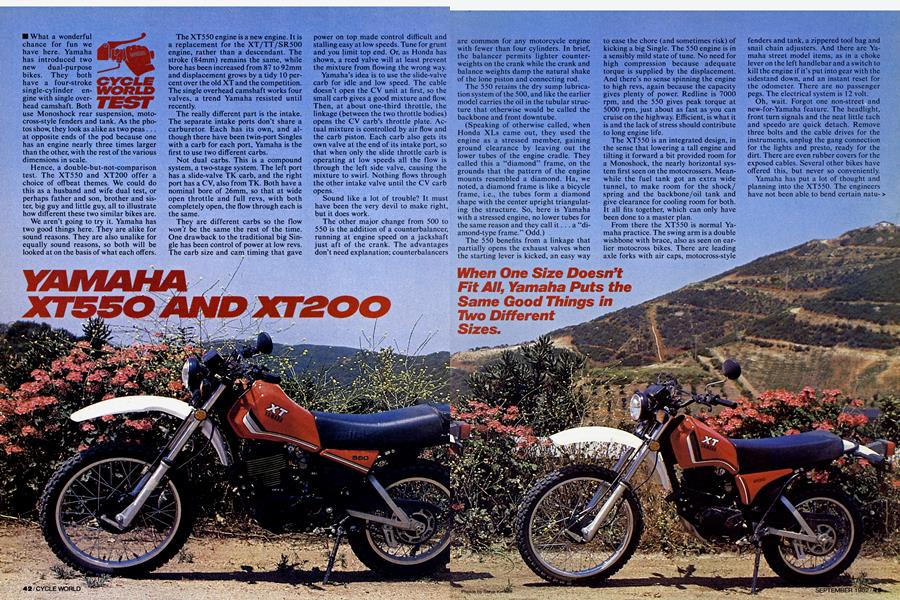

YAMAHA XT550 AND XT200

CYCLE WORLD TEST

What a wonderful chance for fun we have here. Yamaha has introduced two new dual-purpose bikes. They both have a four-storke single-cylinder engine with single overhead camshaft. Both

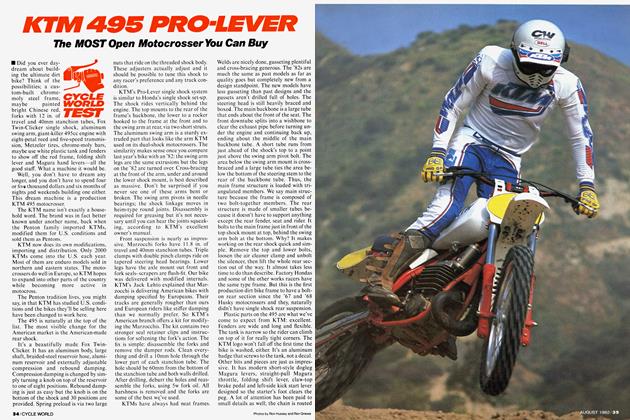

use Monoshock rear suspension, motocross-style fenders and tank. As the photos show, they look as alike as two peas... at opposite ends of the pod because one has an engine nearly three times larger than the other, with the rest of the various dimensions in scale.

Hence, a double-but-not-comparison test. The XT550 and XT200 offer a choice of offbeat themes. We could do this as a husband and wife dual test, or perhaps father and son, brother and sister, big guy and little guy, all to illustrate how different these two similar bikes are.

We aren’t going to try it. Yamaha has two good things here. They are alike for sound reasons. They are also unalike for equally sound reasons, so both will be looked at on the basis of what each offers. The XT550 engine is a new engine. It is a replacement foF the XT/TT/SR500 engine, rather than a descendant. The stroke (84mm) remains the same, while bore has been increased from 87 to 92mm and displacement grows by a tidy 10 percent over the old XT and the competition. The single overhead camshaft works four valves, a trend Yamaha resisted until recently.

The really different part is the intake. The separate intake ports don’t share a carburetor. Each has its own, and although there have been twin-port Singles with a carb for each port, Yamaha is the first to use two different carbs.

Not dual carbs. This is a compound system, a two-stage system. The left port has a slide-valve TK carb, and the right port has a CV, also from TK. Both have a nominal bore of 26mm, so that at wide open throttle and full revs, with both completely open, the flow through each is the same.

They are different carbs so the flow wont be the same the rest of the time. One drawback to the traditional big Single has been control of power at low revs. The carb size and cam timing that gave power on top made control difficult and stalling easy at low speeds. Tune for grunt and you limit top end. Or, as Honda has shown, a reed yalve will at least prevent the mixture from flowing the wrong way.

Yamaha’s idea is to use the slide-valve carb for idle and low speed. The cable doesn’t open the CV unit at first, so the small carb gives a good mixture and flow. Then, at about one-third throttle, the linkage (between the two throttle bodies) opens the CV carb’s throttle plate. Actual mixture is controlled by air flow and the carb piston. Each carb also gets its own valve at the end of its intake port, so that when only the slide throttle carb is operating at low speeds all the flow is through the left side valve, causing the mixture to swirl. Nothing flows through the other intake valve until the CV carb opens.

Sound like a lot of trouble? It must have been the very devil to make right, but it does work.

The other major change from 500 to 550 is the addition of a counterbalancer, running at engine speed on a jackshaft just aft of the crank. The advantages don’t need explanation; counterbalancers are common for any motorcycle engine with fewer than four cylinders. In brief, the balancer permits lighter counterweights on the crank while the crank and balance weights damp the natural shake of the lone piston and connecting rod.

The 550 retains the dry sump lubrication system of the 500, and like the earlier model carries the oil in the tubular structure that otherwise would be called the backbone and front downtube.

(Speaking of otherwise called, when Honda XLs came out, they used the engine as a stressed member, gaining ground clearance by leaving out the lower tubes of the engine cradle. They called this a “diamond” frame, on the grounds that the pattern of the engine mounts resembled a diamond. Ha, we noted, a diamond frame is like a bicycle frame, i.e., the tubes form a diamond shape with the center upright triangulating the structure. So, here is Yamaha with a stressed engine, no lower tubes for the same reason and they call it... a “diamond-type frame.” Odd.)

The 550 benefits from a linkage that partially opens the exhaust valves when the starting lever is kicked, an easy way to ease the chore (and sometimes risk) of kicking a big Single. The 550 engine is in a sensibly mild state of tune. No need for high compression because adequate torque is supplied by the displacement. And there’s no sense spinning the engine to high revs, again because the capacity gives plenty of power. Redline is 7000 rpm, and the 550 gives peak torque at 5000 rpm, just about as fast as you can cruise on the highway. Efficient, is what it is and the lack of stress should contribute to long engine life.

The XT550 is an integrated design, in the sense that lowering a tall engine and tilting it forward a bit provided room for a Monoshock, the nearly horizontal system first seen on the motocrossers. Meanwhile the fuel tank got an extra wide tunnel, to make room for the shock/ spring and the backbone/oil tank and give clearance for cooling room for both. It all fits together, which can only have been done to a master plan.

From there the XT550 is normal Yamaha practice. The swing arm is a double wishbone with brace, also as seen on earlier motocross bikes. There are leading axle forks with air caps, motocross-style fenders and tank, a zippered tool bag and snail chain adjusters. And there are Yamaha street model items, as in a choke lever on the left handlebar and a switch to kill the engine if it’s put into gear with the sidestand down, and an instant reset for the odometer. There are no passenger pegs. The electrical system is 12 volt.

Oh, wait. Forgot one non-street and new-for-Yamaha feature. The headlight, front turn signals and the neat little tach and speedo are quick detach. Remove three bolts and the cable drives for the instruments, unplug the gang connection for the lights and presto, ready for the dirt. There are even rubber covers for the exposed cables. Several other bikes have offered this, but never so conveniently.

Yamaha has put a lot of thought and planning into the XT550. The engineers have not been able to bend certain natu> ral laws, and the test weight, with the generous fuel tank half full, is 316 lb. This compares well with the Suzuki SP500, a more conventional design with a test weight of 3 1 8 lb. by our methods, and isn’t much worse than the class lightweight, if such can be said about the 304 lb. Honda XL500S. (We haven’t tested the XL500R yet, but because the XL250 only gained 5 lb. with Pro-Link, we’ll guess the 500R will still be lighter than the XT550. Other dimensions for the three big Singles are so close, as in 55.3 in. wheelbase for the XT, 55.1 for the XL and 57.5 for the SP, seat heights of 33.4, 33.3 and 34 in., respectively, as to not make much difference.

When One Size Doesn’t Fit All, Yamaha Puts the Same Good Things in Two Different Sizes.

The XT200 proves this in another way. The engine is less than half the displacement, yet both the 200 and the 550 are designed for young or old adults. Any modern motorcycle intended for use off road must have seven or eight inches of wheel travel, and that means ground clearance of eight or nine inches and so on up the scale. The XT200 is therefore smaller than the XT550, but not by as much as the engine is. The wheelbase is shorter, the seat is lower, the fuel tank is smaller, the rear wheel is a 17-incher instead of an 18, the figures showing the 200 to be a nine-tenths scale version of the 550.

Further, bear in mind that in moving from the 550 to the 200, we are skipping one step. In between these two is the XT250, as well as the Honda, Kawasaki and Suzuki 250 four-stroke dual purpose entries, which are just an inch or so bigger most places, and are 30 lb. or so heavier.

This is the main difference. The XT200 tipped the scales at 233 lb. with the smallish ( 1.9 gal.) tank half full. This is an odd displacement, falling as it does between the traditional 125 and 250 classes. The only nearly direct competition is the Honda XL185S, with a test weight of 250 lb. Yamaha’s policy of machines just a bit smaller and lighter than the others in class is fulfilled here.

The general design of the 200 is like that of the 550. Same sort of single rear shock, open cradle frame with stressed engine, motocross style for tank and seat and so forth.

The 200 engine is similar to, but not the same as, the XT125 and sort of a cousin to the SRI 85 Single, while not much like the XT/SR250. The XT200 has a two-valve head and only (!) one carburetor, and it also comes with counterbalancer and compression limiter for starting.

Pricing similar bikes with different displacements is tricky. It doesn’t cost much extra to make one larger piston or use a few additional inches of steel tubing from the frame, etc. But you can’t offer a 200 and a 550 (or a 1 25 and a 250, a 750 and a 900) for the same money.

To make up the difference, the XT200 has a few fewer things. The choke is on the carb instead of remotely linked from the grip. There’s a speedometer and threez warning lights instead of speedo and tach and lights. The 550’s zip-up tool bag is replaced with a plastic lid on the rear fender, covering an indentation for the tools, and the tools themselves are skimpy, lacking for instance the alien wrench you need to get at the valves and including the flimsiest 10-mm open end wrench we’ve ever seen. Because none of the above can be said to impede function -what good is a wrench for the valves if you also need a feeler gauge the term penny pinching is too strong. Call it cost awareness.

The 200 is supposed to function as an all-rounder, on the trails and the highways, ridden by adults, so the engine is tuned some, as in torque peak at 7000 rpm against five thou for the 550, compression ratio of 9.5 instead of 8.5, and most useful and noticeable, the 200 is geared to spin faster at all road speeds.

All of which adds up to a comparison test only in the sense of comparing the same general approach used on two similar machines intended for dififerent people doing the same sort of riding.

Starting the 550 is like kicking a bucket of molasses. The compression limiter has trimmed off the highs, so to speak, and because of that the gearing was picked so you can spin the engine several times per kick. The big piston and crank and counterbalancer add up to a lot of mass to be accelerated. The results is a constant drag on the rider’s foot. While the ordinary engine goes chusa-whump, the 550 does a clug-clug-clug until the lever is all the way down.

No problem. A kick or two is all it takes, hot or cold. The 550 warms in a minute or so (keep the choke full on until then, there isn’t much gradiation) and when it’s warm, it’s wonderful.

The compound carbs work. In most examples of newness, it’s hard to tell exactly. The engine runs fine, and the figures are good so the credit goes to the power valve or swirl induction or something, but all you really know are the figures.

In the 550’s case, any rider with experience on the previous Yamaha 500 Single, or the Honda or Suzuki 500s or previous English thumpers will know right away: The XT550 works better than anything current or previous. It idles and accepts however much or little throttle it’s given. The perfect trials engine, except that it’s just as strong in the middle and pulls right on the redline, no problem at all.

The only sign of technological difference, aside from running better than anything in the class, is the step in the throttle. The same cable and linkage work both barrels, so the throttle is light, then there’s a tiny bumpstop, then it’s heavier and that’s the second carb coming into play. By what cannot be chance, the step comes right about 60-65 indicated in top gear, the natural cruising speed for other reasons. Neat. Efficient. Feeding the incoming charge through only one valve offsets the flow and swirls it, we’re told, and the mixture gets more, well, mixing. Our mpg tester used the step on the highway and got 52 mpg. Plus, the 3-gal. tank gives nearly 150 mi. between fills. > Handling on the road is very good. Steering is quick and takes little effort on the wide handlebars. This can create a disconcerting high speed weave if the rider moves around on the bike at speeds above 65 mph. At lower speeds it corners easily, the tires feeling better than expected. Suspension travel is more than

adequate for big bumps, but on small surface changes it doesn’t absorb enough motion so the ride can be a bit rough. Power is such that the 550 can be ridden aggressively, in the sports manner, with blasts to take advantage of spaces in traffic, leans into the turns, the whole bag of fun riding methods.

The critic’s vocabulary is a bit weak here. Now that we have different ways to mount engines, different configurations

for engines, counterbalancers turning up everywhere we look, it’s no longer enough to say the engine vibrates a lot or a little or too much. Our scale isn't fine enough.

The 550 vibrates. More than a Seca 400, less than the XT200 or XT250, more than a Vision or Seca 750. It’s a medium amplitude, low frequency vibration. Feels like one cylinder, under control. There are no awkward periods, the bars don’t numb the hands, and the only measurable debit was that with non-rubbersoled boots, the vibes walk the right foot off its peg unless the foot is held inward. Not too bad, in other words.

There was some comment before the actual testing about why Yamaha didn’t fit the XT550 with the double leading shoe front brake already made for the big YZ and IT. Simple. The leading-trailing brake works fine, providing excellent stopping distances.

The 550 has a pleasant clutch, engaging with little travel, but the shift of our example was balky and sometimes hung up on the edge of going into gear, usually 1st or 2nd. This caused a stumble or two in the dirt.

The 550 makes a super commuter scooter in the city, and it’s adequate on the open road. The power is there and the gearing keeps the engine from being too busy or sounding too busy. The high and wide bars sit the rider up, as they should for dirt, but headwinds are a hardship on the road. The seat is too motocross, as in Honda’s XL series, and the narrow and square shape is a pain in the logical place.

For trailing or exploring, with the rider shifting around and standing up and stopping frequently, it's an all day seat. On the highway, perched in the same spot without much else to do, the 550 and the 200 both become annoying.

The penalty for weight shows up in the dirt. The 550 is just fine for graded or gravel roads. But the farther off road it goes, the more it's work to ride. The 550 is big, as noted. It carries the weight high, what with the big tank, the oil supply and the rear shock all above the engine. Great grabs of body English are needed to keep the bike on the desired line. The forks work just about right, while the rear shock can be bottomed off drops and into ditches. This is a straight spring rate and travel is no more than adequate for use.

Some of the time the power redeems the chassis. If the front wheel wanders in a tight stream crossing and the tire comes to rest against the boulder you wanted to avoid, well, at least the engine has enough muscle to grunt the bike over the boulder. And if you can't pick your way around ruts, you can power your way across them.

That works best for the big and bold, not incidentally. Our fastest man is also our heaviest, and he did better than our lighter and slower riders, who sometimes felt like the tail to the 550's dog.

The rear wheel will kick over choppy ground, and the faster you're going the harder it kicks. Finally, the weight and the short swing arm make powerslides more like sawtoothed cornering.

The XT550 isn’t an IT465. But it will take you nearly anyplace any dirt bike can go, and it’s so much better off road than the XT500 ever hoped to be, it’s almost a shame to report less than perfection.

The XT200 is smaller.

That’s shorthand, obviously. But the two machines do feel alike, and act alike except that one isn't as big as the other.

Thus, the 200 also lacks the feel of compression w hen kicked, but the mass is much less. For the 200 it’s jabjabjabjab and the engine is running. A mile or so on choke and it’s ready. What it isn't, is quick. Again the numbers are respectable, you can get briskly through the traffic, etc. Thing is, it takes more planning and more revs to do it. The smaller engine with counterbalancer is naturally even smoother than the big engine, while gearing for adults on the public highway means spinning the 200 faster at all road speeds, it feels okay and there are no bad periods or buzzing of note. The 200 will maintain 65 on the highway with a bit in reserve, even against a headwind, while that speed is also close to maximum. Passing slower traffic means shifting. And while the engine didn’t seem to suffer at highway speeds, on occasion it was reluctant to idle after half an hour in the fast lane, so 60 is probably the reasonable limit.

This showed up on the mpg test as well. The result, 68 mpg, will turn Datsun owners green. But 68 mpg is just about what the Yamaha XS400 does, with twice the displacement and a more relaxed cruising speed.

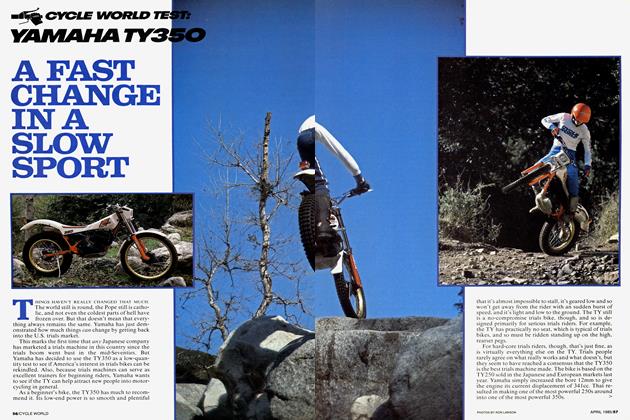

Off road, the handling is part just-alike and part mirror image.

The Bridgestone universal tires on both the. 200 and the 550 grip the pavement, work in sand and on rock and pack with mud, and get slippery when wet, so that’s alike.

The 200’s forks are fine, while the rear suspension can be bottomed and will kick, again alike. The difference is that because the 200 is 80-odd lb. lighter, it kicks less, and the rider has less machine to wrestle, which works out to a more forgiving bike. It can be raced across choppy ground with less fear, first because the sideways jumps are less violent and second because it isn’t as fast.

(We shouldn’t forget that this applies with the same rider on either bike, that is, a 200-lb. occupant will have less trouble with the 550 while being too big for the 200, and a 125-lb. rider isn’t big enough for the 550, motocross pros aside.)

The mirror image involves steering. The 200 steers better; less mass to get aimed right. So the ruts the 550 must be slammed over, the 200 can be steered around. The 200 will negotiate the rocklined stream bed. so it doesn't matter it can’t blast over the boulders because it's not going to hit them.

When the wizard grants our wishes, we'll arrange for a lighter 550 and a 200 with more torque, better seats and better wrenches. As long as we’ve got his attention, some adjustment on the rear shock, too.

But those are quibbles. Meanwhile, the XT550 and XT200 are good machines. They’ll work wherever they go and they'll go just about anywhere, while the difference in size means the rider doesn't have to choose between them. One size doesn’t have to fit all. because the XTs come in all sizes. S

YAMAHA

XT550

$2199

YAMAHA

XT200

$1299

View Full Issue

View Full Issue