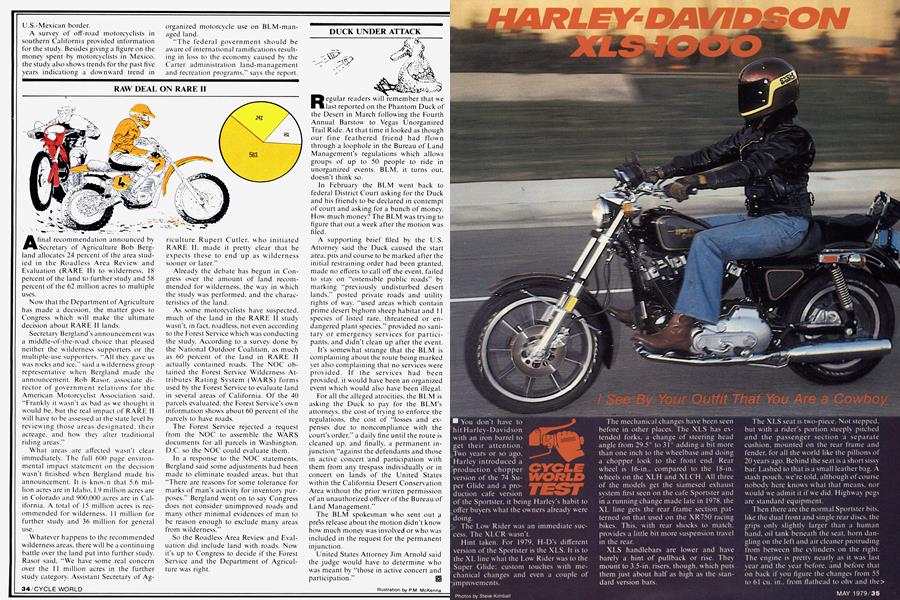

HARLEY-DAVIDSON XLS-1000

CYCLE WORLD TEST

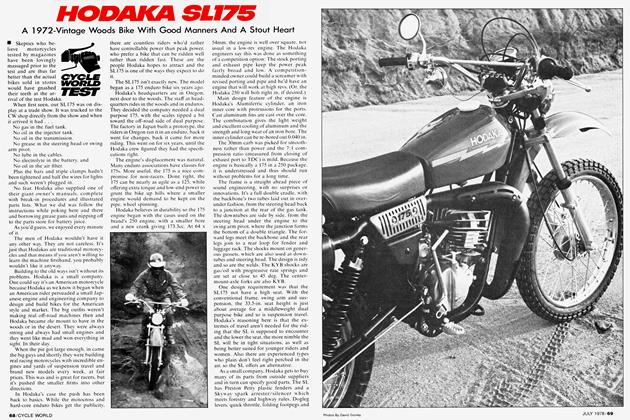

I See By Your Outfit That You Are a Cowboy

You don't have to hit Harley-Davidson with an iron barrel to get their attention. Two years or so ago, Harley introduced a production chopper version of the 74 Super Glide and a production cafe version

of the Sportster, it being Harley’s habit to offer buyers what the owners already were doing.

The Low Rider was an immediate success. The XLCR wasn't.

Hint taken. For 1979, H-D’s different version of the Sportster is the XLS. It is to the XL line what the Low' Rider was to the Super Glide; custom touches with mechanical changes and even a couple of improvements.

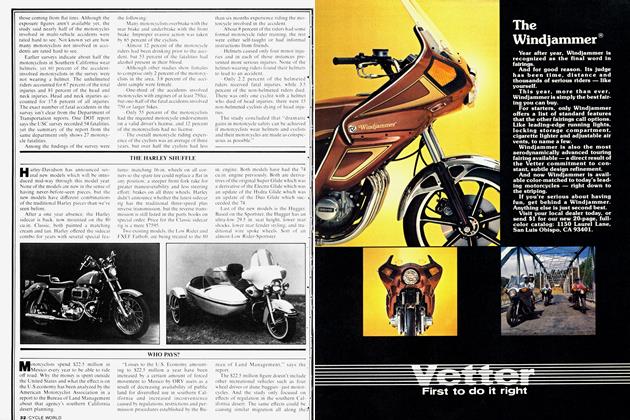

The mechanical changes have been seen before in other places. The XLS has extended forks, a change of steering head angle from 29.5° to 31° adding a bit more than one inch to the wheelbase and doing a chopper look to the front end. Rear wheel is 16-in., compared to the 18-in. wheels on the XLH and XLCH. All three of the models get the siamesed exhaust system first seen on the cafe Sportster and in a running change made late in 1978, the XL line gets the rear frame section patterned on that used on the XR750 racing bikes. This, with rear shocks to match, provides a little bit more suspension travel in the rear.

XLS handlebars are lower and have barely a hint of pullback or rise. They mount to 3.5-in. risers, though, which puts them just about half as high as the standard version bars.

The XLS seat is two-piece. Not stepped, but with a rider’s portion steeply pitched and the passenger section a separate cushion, mounted on the rear frame and fender, for all the world like the pillions of 20 years ago. Behind the seat is a short sissy bar. Lashed to that is a small leather bag. A stash pouch, we’re told, although of course nobody here knows what that means, nor would we admit it if we did. Highway pegs are standard equipment.

Then there are the normal Sportster bits, like the dual front and single rear discs, the grips only slightly larger than a human hand, oil tank beneath the seat, horn dangling on the left and air cleaner protruding from between the cylinders on the right. The engine is pretty nearly as it was last year and the year before, and before that on back if you figure the changes from 55 to 61 cu. in., from fiathead to ohv and the> like are merely updates.

What sets the XLS off most is the paint and trim. The bodywork gets black and deep metallic charcoal paint, the rear sprocket is chrome-plated and various other mechanical parts get chrome or a silver and crinkle-black finish. There’s hand painted striping for the tanks, the H-D logo on the gas tank is gold. The subtle and different paint and polish works with the cast iron steering head, rough vs smooth, to produce a motorcycle the eye cannot resist. It’s tough, it’s attractive and

there ain’t nothing on the XLS doesn’t look like a motorcycle. To see the XLS is to know that all those people who’ve tried to add bodywork to bikes were wrong and deserved what they got. (Quick financial disaster, in case you’re too young to remember.)

There's a touch of the cowboy in all of us. Covering up a machine like this makes ‘as much sense as putting a roof on a horse.

Which may be why the Sportster is what it is, no more and no less.

What Harley-Davidson set out to do with the Sportster, and the K and KH before it, was to build a sporting and highperformance motorcycle, in contrast only with the 74. which was the touring Harley and for all practical purposes was the only other big bike then on the market.

In 1962. this magazine’s first year, we tested the Sportster of the day. Perfectly normal machine, with a fuel tank like the other bikes had and a two-person bench seat, hardly any suspension travel, kick start only. It was the fastest and quickest motorcycle we tested that year and we remarked about this in a calm way. There were, after all, few other contenders for the Superbike title because there were no other Superbikes. There was the Sportster, with optional solo seat, etc., with a small headlight because the big Harleys got the big lights, with a teardrop tank or a touring tank because the Sportster was sold to everybody who wanted a big powerful Twin and that’s all there was:

Things changed, with larger motors from the other outfits, two-stroke Twins and Triples, the Honda Four and the Kawasaki Z-l, while the Sportster stayed much the same. No point in H-D invading the big bike market. H-D was the big bike market. The others invaded and innovated and the market grew beyond what Harley and Davidson ever dreamed possible.

And the Sportster found itself in a selfmade gilded cage.

There never was a time the company could say, better do some radical revision. The guys who wanted Sportsters wanted By God Sportsters. A transverse Four might drive off the customers in hand with no assurance of luring the customers out there in the bush. And before you knew what to make of that, the others surveyed the riding public and discovered what> Harley knew without asking, that is. what a motorcycle is supposed to look like. Round, as one of the other factories says it. as opposed to Square. Teardrop tanks, a flowing line curving across the top of the tank and down below' the seat.

Those Customs and Specials and Limiteds aren’t Harley copies, not directly. It’s just that Harley knows its customers while the rivals survey them, so Harley got there first.

Another thing. These government regulations. The limits aren’t based on exhaust noise, although that’s what the public talks about. With ignition oft', a chain-drive, air-cooled Twin makes more noise than does a shaft-drive, water-cooled Four. Making up some numbers, if the rest of the bike makes, say. 50 decibels and the limit is 80, you got 30 decibels for intake and exhaust. If the rest makes 40, you got 40, and that’s why the Honda CX500 has a throaty exhaust note and the XLS has a big megaphone wdth an exit as big as your thumb, and an air cleaner the size of a breadbox.

No fear. None of the above really matters.

What matters is that despite the vintage engine and the limits imposed on it from within and without, York and Milwaukee have done good.

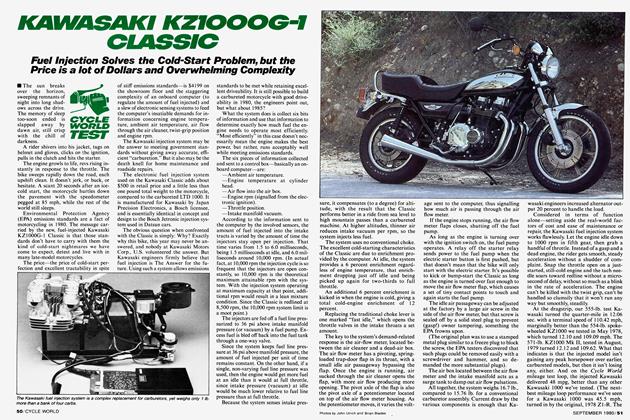

You have read here recently about how' the technowhiz Multis are giving us fits on cold mornings. Gleaming labs, swarms of technicians and the confounded engines greet the dawn’s early light like a schoolkid, that is, cough, moan, grumble and wake ’em up three times before they can stumble forward.

Pull the choke, turn the key and hit the button and three spins later the XLS engine is running and ready to go.

It will pull like a train oft'idle, and wind (well, relatively) easily. The only sign of any compromise with the mixtures and such is that w hen warm, on cruise and light throttle, 55 or 60 mph. every 10 miles or so the mighty Twin goes Bruuk! and then carries on as if nothing had happened. Normal, the Harley man tells us and no, he’s not allowed to hint that perhaps raising the needle one notch would smooth out the glitch.

Punchline. The EPA has just finished doing some compliance testing, finding out which motorcycles meet the rules they're supposed to meet, and by how much. The winners, cleanest of the clean? The Harley V-Twins.

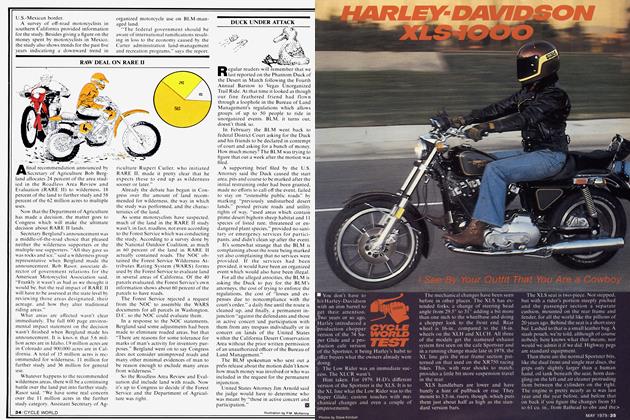

The compromises dictated by the conflict of Sportster buyers vs economics and the law' appear first in ride and handling. The XLS is in effect a frame and suspension built around an engine. A large and heavy engine, while the machine must be relatively small and low. The Sportster is small for its weight, so to speak, with the mass concentrated in the center and without much room for wheel travel. The extended fork brings with it highway ease and low-speed awkwardness, aided and abetted by the bars and seat. Despite the running changes over the years. as the factory has moved this and that and beefed here, trimmed there, the XLS frame remains just about as it was when rear suspension was introduced, that is. not obsolete but surely not the state of the art.

There is a certain suppleness to the frame and that means the practical cure is to supply a certain firmness for the suspen sion. Working with this, the low machine and consequent lack of wheel travel mean they dare not let the suspension move too much.

The ride is hard. More than firm. The forks can be seen and felt working up and down, the rear shocks can't. Our notes from the past, in particular the XLCR. indicated the stiffness was something new

and it is. The first XLCR, one occupant only. had lower rate springs. When the model gained passenger space, the springs were stiffened, and when the CR's rear frame section became standard Sportster equipment, the stiff springs went with it. The XLS faithfully follows every bump in the road, large or small, for the hardest, most choppy ride we've had in years. Handling is more a matter of control. The laid-back low seat doesn't match the forward-mount drag bars. The initial reac tion is fine, as the rider assumes a modified, racer crouch. But having the seat mounted aft, the pegs forward and the bars extra forward leans the rider off balance. The narrow bars reduce lean leverage. Low speed balance requires attention, fast work in the curves is never quite comfortable the XLS tracks and steers well enough, wobbles just a bit, but never feels as if there’s a Superbike raeer hiding in there somewhere.

A more genuine shortcoming concerns the air cleaner and the highway pegs. This isn't Harley’s fault. The law requires quiet and as mentioned when you have lots of mechanical noise, you cannot have intake or exhaust noise. A quiet intake means a big airbox and the XLS box is so big that it gets between the rider’s right leg and the peg. All our riders, even the staff stork, commented on this. Too bad, as the pegs ht the Sportster image just fine.

Also normal is the Harley control system; clutch and brake pull Charles Atlas could learn from, turn signals that only come on when you keep your thumb on the button, key and choke tucked away on a panel below the tank. Shrug. If you can’t handle that, you probably wouldn’t be happy with a Harley anyway.

More to the point, the clutch and shift worked line, the brakes stopped the bike within respectable distances and with good control. There is nothing wrong here. The XLS is different, is all.

What you get is an honest motorcycle. Numbers mean nothing when you muscle off the line, the legendary V-Twin making all those raw and romantic sounds as second gear comes at the torque peak and the flat bars strain your arms. The XLS is a reaffirmation of what motorcycling is, for motorcyclists who’ve always been motorcyclists.

The XLS is the cowboy’s horse, built for and cherished by those of us who’ve always had a touch of cowboy.

Not even Harley-Davidson can explain this. The appeal is as strong and as established as it is difficult to define.

Case in point. Some of the people on the various motorcycle magazines are forming a motorcycle press association. One of the organizational meetings was held on a cold and rainy night. Only three guys rode to the meeting. Each was on a Harley.

Our man wasn’t elected to the board of directors because he arrived on the XLS. But it didn't hurt.

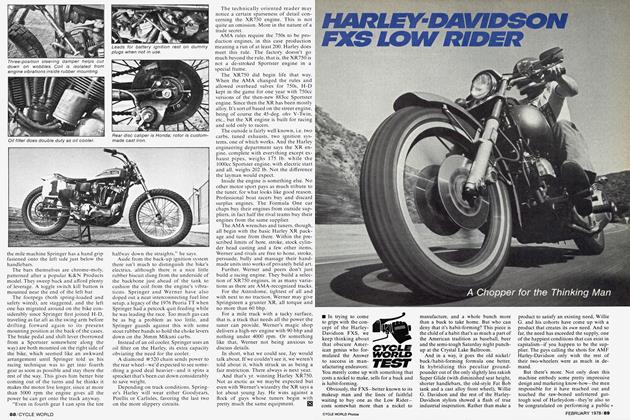

HARLEY-DAVIDSON XLS-1000

$3995

SPECIFICATIONS

ACCELERATION

PERFORMANCE