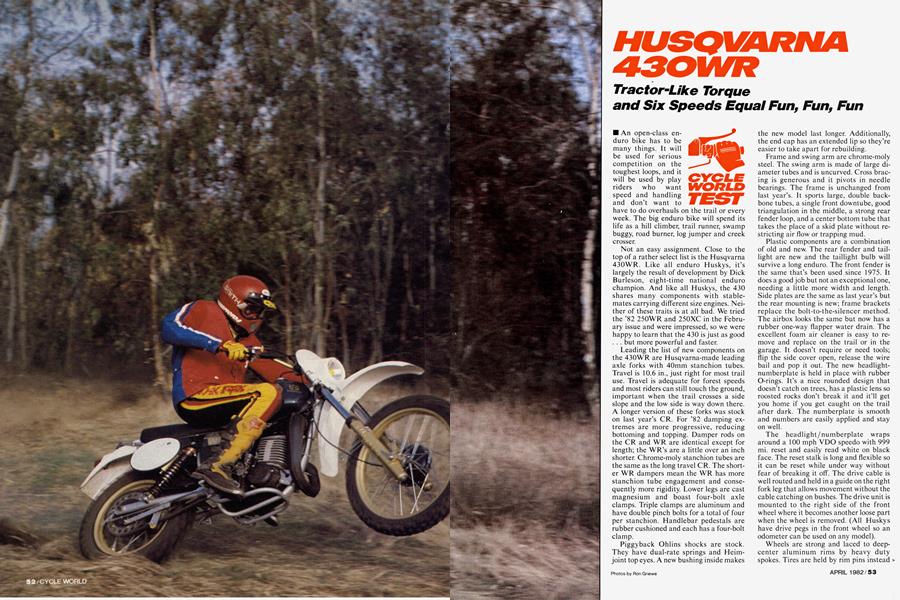

HUSQVARNA 430WR

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Tractor-Like Torque and Six Speeds Equal Fun, Fun, Fun

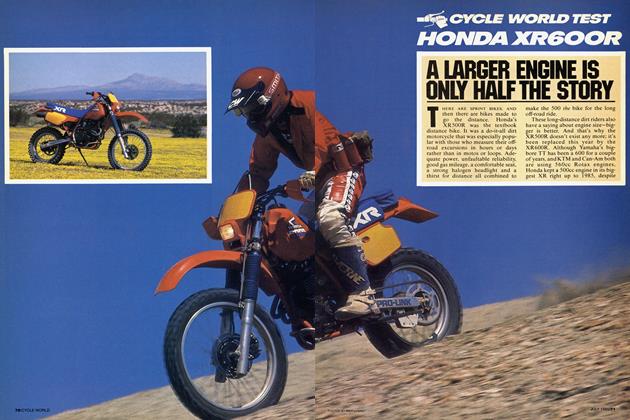

An open-class enduro bike has to be many things. It will be used for serious competition on the toughest loops, and it will be used by play riders who want speed and handling and don't want to have to do overhauls on the trail or every week. The big enduro bike will spend its life as a hill climber, trail runner, swamp buggy, road burner, log jumper and creek crosser.

Not an easy assignment. Close to the top of a rather select list is the Husqvarna 430WR. Like all enduro Huskys, it’s largely the result of development by Dick Burleson, eight-time national enduro champion. And like all Huskys, the 430 shares many components with stablemates carrying different size engines. Neither of these traits is at all bad. We tried the ’82 250WR and 250XC in the February issue and were impressed, so we were happy to learn that the 430 is just as good . . . but more powerful and faster.

Leading the list of new components on the 430WR are Husqvarna-made leading axle forks with 40mm stanchion tubes. Travel is 10.6 in., just right for most trail use. Travel is adequate for forest speeds and most riders can still touch the ground, important when the trail crosses a side slope and the low side is way down there. A longer version of these forks was stock on last year’s CR. For ’82 damping extremes are more progressive, reducing bottoming and topping. Damper rods on the CR and WR are identical except for length; the WR’s are a little over an inch shorter. Chrome-moly stanchion tubes are the same as the long travel CR. The shorter WR dampers mean the WR has more stanchion tube engagement and consequently more rigidity. Lower legs are cast magnesium and boast four-bolt axle clamps. Triple clamps are aluminum and have double pinch bolts for a total of four per stanchion. Handlebar pedestals are rubber cushioned and each has a four-bolt clamp.

Piggyback Ohlins shocks are stock. They have dual-rate springs and Heimjoint top eyes. A new bushing inside makes

the new model last longer. Additionally, the end cap has an extended lip so they’re easier to take apart for rebuilding.

Frame and swing arm are chrome-moly steel. The swing arm is made of large diameter tubes and is uncurved. Cross bracing is generous and it pivots in needle bearings. The frame is unchanged from last year’s. It sports large, double backbone tubes, a single front downtube, good triangulation in the middle, a strong rear fender loop, and a center bottom tube that takes the place of a skid plate without restricting air flow or trapping mud.

Plastic components are a combination of old and new. The rear fender and taillight are new and the taillight bulb will survive a long enduro. The front fender is the same that’s been used since 1975. It does a good job but not an exceptional one, needing a little more width and length. Side plates are the same as last year’s but the rear mounting is new; frame brackets replace the bolt-to-the-silencer method. The airbox looks the same but now has a rubber one-way flapper water drain. The excellent foam air cleaner is easy to remove and replace on the trail or in the garage. It doesn’t require or need tools; flip the side cover open, release the wire bail and pop it out. The new headlightnumberplate is held in place with rubber O-rings. It’s a nice rounded design that doesn’t catch on trees, has a plastic lens so roosted rocks don’t break it and it’ll get you home if you get caught on the trail after dark. The numberplate is smooth and numbers are easily applied and stay on well.

The headlight/numberplate wraps around a 100 mph VDO speedo with 999 mi. reset and easily read white on black face. The reset stalk is long and flexible so it can be reset while under way without fear of breaking it off. The drive cable is well routed and held in a guide on the right fork leg that allows movement without the cable catching on bushes. The drive unit is mounted to the right side of the front wheel where it becomes another loose part when the wheel is removed. (All Huskys have drive pegs in the front wheel so an odometer can be used on any model).

Wheels are strong and laced to deepcenter aluminum rims by heavy duty spokes. Tires are held by rim pins instead of rim locks, making tire changes easier and improving wheel balance. Tires are long-lasting Barums. The front didn’t work especially well but the rear was fine in sand and dry ground. Add wet ground or snow and the rear also becomes barely usable. For desert conditions the 17 inch rear Barum will outlast two of any other brand. Barum red-rubber inner tubes are stock on the WRs. They are generally accepted as the best. They’re thick and made from real rubber. Rim bands stay put while changing tires and appear to be glued to the rims.

Both brakes are single leading shoe. The front has a slightly longer backing plate arm this year. The rear has the same length arm as last year’s. Both brakes have wider linings that go away when wet but return quickly with light application of the levers. The WR doesn’t use the full-floating rear backing plate like the CR. The WR and XCs have a non-floater with a short aluminum static arm attached to the swing arm. The previous full-length arm had a problem dragging in rocks and shearing the 6mm bolt. The new WR and XC set up has an 8mm bolt and it isn’t attached as low on the backing plate. End of problem. Don’t worry about brake chatter with the new system—it doesn’t. A redesigned rear brake pedal positions the brake rod end over the swing arm pivot and eliminates the possibility. Additionally, the new brake lever has a claw top to eliminate boot slip during muddy events. And the new lever is shorter and stiffer, end of another common complaint.

The rest of the controls are of equal quality: the shift lever has a folding tip, hand levers are Magura dog-leg models with long cable adjusters, the throttle is a Gunnar Gasser, handlebars are chromemoly and shaped right for most riders, grips are fine, lever covers are standard equipment and the kill button is water1 proof. There’s even a stop light switch in the front brake lever perch if one is needed. The headlight burns all the time so there’s no need for a switch. There’s also a place on the rear brake pedal for a brake light switch if needed.

Gasoline capacity is 2.9 gal. Husky is the only manufacturer still using aluminum for gas tanks on dirt bikes. The tank is nicely made, has exposed aluminum sides and thickly applied paint. The metal sides have been a Husky trademark since 1967 when the first Huskys came to America. Their function is simple; normally the rider’s legs rub the paint from the sides of the tank, so Husky leaves the paint off this area, pin stripes the paint border and clear coats the entire tank. Thus, Huskys retain that new look a lot longer.

Older Huskys had big thick seats that desert racers loved. Most were sad when the newer bikes went to a trimmer and thinner seat, necessary to keep the seat height at reasonable levels with 12 in. of wheel travel. The ’82 still has a rather thin seat but the foam density is better and the seat is comfortable. It doesn’t pack down and the edges are rounded so it doesn’t rub the inside of the rider’s legs. The seat base is plastic, like last year, but thicker and stronger.

Perhaps the best part of the bike is the engine. It has 430cc, a six-speed transmis-

sion, primary kick starting, 38mm Mikuni carb., reed induction, straight-cut primary gears, strong multi-plate clutch and a 140 watt Swedish-made SEM ignition. On paper the motor sounds like last year’s: It is but with several improvements: The gears are put through an additional hardening process for increased strength, the clutch basket has no lightening holes and the aluminum is harder. Magnesium cases are beefed around the rear engine mounts. The SEM ignition comes with dual 70w wires, powering the tail light and both headlight filaments. The system includes a regulator, which takes care of the surplus wattage. Installing a 1 OOw quartz-halogen headlight or heatecfigrips should be easy.

Some are quick to criticize Husky’s strange kick start lever. Actually it’s quite clever. The weird bend places it out far enough so the starter’s foot never hits the footpeg, a welcome change. And it doesn’t use a spring-loaded ball to keep it from falling out when at rest. The reasoning is simple; most levers that use the spring-ball system, meaning almost all other brands, have a problem getting clogged by mud. It can be very annoying and you can lose valuable positions trying to pry a stuck kick lever out. Husky uses a friction swivel and an engine-mounted bracket to hold the lever in—no jamming in mud. Past models have had problems with the plastic engine bracket breaking, the ’82 has a beefier bracket. As soon as they replace the lever’s rubber cover with cast-in ridges it’ll be perfect.

Husky engines are simpler to work on than many. The engineers have used snap rings in place of conventional nuts where possible. The countershaft sprocket, clutch basket and kick lever are secured with snap rings. Removing the clutch side cover is another simple job on a Husky; no need to remove the shift lever or kick lever, just lay the bike on its right side, remove the alien screws and lift the cover off. The shift lever plugs in, the kick lever mechanism lifts off with the case, Simple. Even oil changing is easy; the drain plug is easily reached on the right side and the filler hole is large and convenient.

Starting an open-class Husky is seldom a one kick operation. The starting mechanism has good mechanical leverage which makes the big Husky easier to kick over than other open bikes, but it doesn’t engage until it’s part way through its arc, and it requires several quick prods before the engine comes to life. The lever is on the left side of the bike, a placement favored by Husqvarna for a long time and it makes kicking the engine over much easier for a short rider. It’s easier to stand next to a tall bike and kick with one’s right foot than try and stradle a tall seat while kicking. Experienced Husky riders (the taller ones) start them while sitting on the seat and kicking with the left foot. Once the rider is used to the short kick throw the bike will sometimes start first kick when warm if the engine is spun quickly, but it almost always takes three or four quick stabs when cold. After the engine fires it’s necessary to fold and lift the kick start lever to its engine bracket. After a little practice it becomes easy to do it with your foot instead of by hand. Experienced Husky riders don’t even realize they are doing it. Primary kick is standard and works quite well for an open class bike. Clutch drag while starting in gear is minimal but there. We found it easier to use neutral when the engine is cold as the engine turns quicker and fewer prods are required to bring it to life. When warm, with gearbox oil thinned and circulated, the primary kick works well and makes restarting in a mud bog quicker and easier.

The 430WR is an amazing machine. Fully competitive for an overall win in a national enduro straight from the shipping crate, it also makes a wonderful trail bike. The tractable engine with its heavy flywheels and wide-ratio six-speed transmission are the major reasons. The 430 is usually delivered with a 12 tooth countershaft sprocket, ours came with an 11 tooth and a note telling us about the change. “Try it, we think it works better with the eleven tooth,” said the Husqvarna folks. It worked so well we never did^ try it with the 12. First gear will let the bike crawl around at sub-walking speeds, sixth is good for a VDO-indicated 90mph! What a pleasure to be able to ride in the forests, desert or Baja’s fire roads without changing gearing.

The WR comes with a large silencer/4 spark arrester that keeps the exhaust note fairly quiet, and legal in forests. And the cylinder’s fins are thick and tied together by a cast-in bridge that adds strength and reduces fin rattle. The silencer’s end cap is easily removed using the supplied spring removal tool. And it’s a good idea to use itv regularly. The end cap contains a fine wire screen that should be cleaned often. If it isn’t, the screen will clog and reduce top speed and produce a high rpm blubber.

HUSQVARNA 430WR

$2820

The WR430 is nearly perfect for woods use. Ten and a half inches of wheel travel is enough for almost any trail need and the low seat height is appreciated when it becomes time to paddle or dab or simply put your foot down firmly. The low center of gravity and short wheelbase also become a plus for blasting down tricky, tight, brushy trails. It is much quicker handling than the spec sheet would indicate. Normally bikes with 30° rakes aren’t the quick handlers. For quicker steering the stanchion tubes can be raised up to 3/4-in. in the triple clamps. Anyone who has heard “Huskys don’t turn well” should try one that’s been set up properly. They will turn with or under the brands with the best reputations. No muscle or fighting is required when set up right.

We wondered why Husky didn’t go to single shock rear suspensions. Husky explained it simply: “We aren’t convinced single shock suspensions are better—just different. Our double shock set up is progressive and has proven to work well. We have a prototype single shock but like the double better. Dual shocks sit out in the airflow and don’t fade as quickly as a single that’s buried in the middle of the bike. We don’t change for the sake of change.” Their words stuck in our heads as we blasted through the trees on the first outing with the WR430. Indeed, Husky’s dual shock works well, in fact we couldn’t think of a single shocker that works any better. And the front end works as well as any we’ve ridden. The bike reacts easily to small bumps and doesn’t bottom harshly, or pitch or kick when smashing into tree roots and holes. It wasn’t even necessary to adjust the shock’s spring preload or change the fork oil level or weight. It’s dialed perfect for the woods as delivered. We ventured out to the Anza Borrego Desert and found the WR well suited for that use, but not as good as it was in the mountains. It’ll go through deep whoops amazingly fast although it bobs around some and bottoms when going all out. Still, it never once jumped sideways or got out of control. Husky makes a desert enduro model called XC that has 12 in. of travel for those who need more suspension. For occasional desert use, though, the low seat height WR isn’t a bad choice.

Fuel usage was a surprise. The WR430 will go farther on a tank (2.9 gal. on the 250 and 430WRs) than the 250. We could count on 60 mi. per tank with an expert rider, more with a novice. Gasoline quality didn’t matter either. Even the worst gas didn’t cause pinging. Carburetion was just a little rich as delivered but we left it alone until the bike had a couple hundred miles then dropped the needle one notch. That cleaned it up and made the mid-range spot on.

Husky’s ’82 430WR is one of those rare machines that everyone had fun riding. Mountains, desert or anything in between, the WR will take you there and back with minimal maintenance and no special preparation. And chances are you’ll be grinning all the way.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue